Coronavirus: Sweden goes it alone but will it work?

It has a higher death rate than other Nordic countries, but Sweden is choosing not to follow the herd on COVID-19. Will its risky eperiment work?

The borders are open in Sweden, as are the cafes and elementary schools, and the only thing stopping the country’s 10.1 million citizens from heading to their summer houses and ski slopes for Easter is Nordic pragmatism and a prime ministerial appeal for everyone to act like adults.

In years to come, scientists will study this Scandinavian country — not an obvious nation of risk-takers — for its risky COVID-19 experiment that is maybe two parts sociological and eight parts epidemiological.

“Us adults need to be exactly that: adults. Not spread panic or rumours. No one is alone in this crisis but each person carries a heavy responsibility,” Prime Minister Stefan Lofven said this week.

Yet there is no mandatory policy, no penalties for defying his appeal.

Over the Oresund Bridge from Sweden’s third city of Malmo, Denmark’s borders are closed, its bars, restaurants and malls shut and gatherings of more than 10 people banned.

Finland also has shut its borders, while Norway has limited outdoor gatherings to five people.

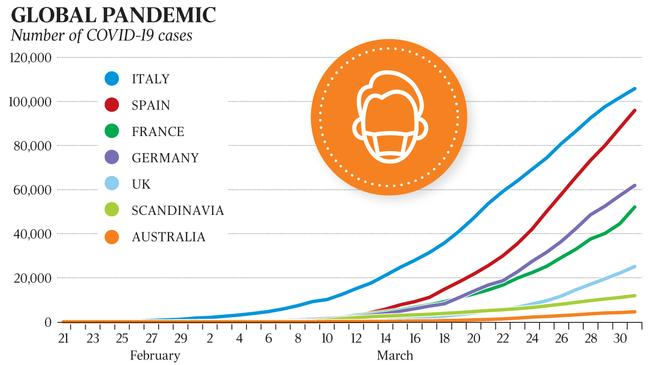

Across Asia and Europe, countries have gone into varying states of lockdown, cowered by harrowing footage streamed daily out of Italy, Spain and now even New York showing modern health systems crumbling under the onslaught of the virus.

Italy’s suffering frightened many Western governments into applying unprecedented — even previously unthinkable — social restrictions to control the spread with strict penalties, even jail terms, for violators.

The country with the second oldest population in the world, after Japan, now has a horrifying COVID-19 mortality rate of 11.7 per cent, with more than 12,428 deaths from 105,792 cases (partly explained by its testing only of those with the most severe symptoms).

Spain, Italy, Poland, Belgium, even libertarian France — which now has more than 52,836 coronavirus cases and 3523 deaths — are all in total lockdown as are Jordan, Israel, the Czech Republic, Peru and Argentina.

Just as intensive global co-operation is needed most, nations are turning inward, locking down and in some cases adopting a sort of “scarcity nationalism” as they grapple with the worst public health crisis in generations.

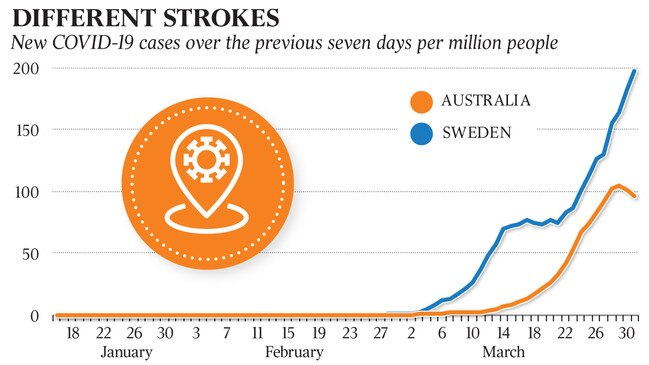

Yet the picture is different in Sweden, which is attempting to “slow the curve” without shutting down the economy.

Sweden is functioning largely as usual as it tries to slow the spread of the virus while building herd immunity, a strategy similar to that flagged, then dropped, by the British government after modelling showed it could result in 250,000 deaths.

Swedes are still socially distancing — those with COVID-19 symptoms are self-isolating — but the government has entrusted its National Institute of Public Health to set the country’s COVID-19 policy, and its people to follow its advice.

“It’s not a political decision but a science-based one and Swedes have a lot of trust in authorities and public agencies to act in the public interest,” says Paula Alvarado, a Peruvian-born development specialist who has lived and worked in Sweden for eight years.

“The instructions are self-distance, wash your hands frequently, stay away from people over 70, and that’s what people are doing.

“Self-isolation looks different for different people, but if you need to go to the supermarket and there are 15 people looking at the cheese you go to another aisle. You give each other space.”

But Swedish scientists are divided on the strategy.

One mathematician has accused authorities of “playing Russian roulette” with the population. A group of infectious disease professors has called for Sweden to “shut down everything that’s possible to shut down” as quickly as possible.

Sweden’s neighbours also are scratching their heads and foretelling doom, just as Japan’s apparently freewheeling approach to the COVID-19 pandemic has done among its dour East and Southeast Asian neighbours.

There, too, life continues, if not as normal, at least more so than most other countries.

There has been no South Korean-style testing drive (though there is extensive contact tracing to identify infection clusters), shops and restaurants are open, and some schools will reopen next week after two months of closures.

Some have attributed Japan’s apparently low COVID-19 caseload to cultural influences — its tradition of bowing rather than shaking hands, its hygiene obsession, the long acceptance of face masks, and “social obedience”.

Like the Japanese, Swedes who back their country’s strategy (many also don’t) cite a national tendency for “social obedience” as a reason tighter restrictions are not required.

Social distancing is also a way of life in the sparsely populated country. It has an advanced digital economy that already allowed many people to work two or three days a week from home, and strong health and social welfare systems.

Lund University epidemiology professor Paul Franks says Sweden’s strategy is based on what it predicts its health system’s capacity will need to be to meet the projected peak of very ill COVID-19 patients needing specialist care in coming weeks.

Swedish modelling anticipates far fewer hospitalisations per 100,000 people than predicted in Norway, Denmark or Britain, and predicts a slowing of cases as the weather warms and more people are infected.

Applying British simulations, however, projected deaths are far higher.

Franks cautions against applying the experience of one country to another in the current uncharted territory.

“You can look at China and Italy, or previous flu pandemics or SARS or MERS, but none very easily parallel to the situation in Sweden or even Australia,” he says. “Mediterannean countries have likely been hit harder because of social cultural factors; more old people are living in homes with younger people, it is a more physically intimate society.”

In Sweden’s case, Franks is hoping for the best but bracing for the worst.

“If you look at the pattern of deaths in Sweden, it’s not looking great. Sweden has more deaths per 100,000 than other Nordic countries,” he says.

Sweden and Norway (which has half Sweden’s population) both have about 4500 COVID-19 patients, but Sweden has had 180 deaths to Norway’s 39.

“In two or three weeks there will be a fairly clear picture of whether the ICU requirements predicted by public health authorities has been correct, and I hope to God it is because if it is not, that’s when you go over a tipping point and you don’t just lose people from COVID-19 but people with all sorts of medical emergencies.

“On the one hand we are probably going to have a very high number of deaths in a short period because we don’t have strong containment strategies, but we will then be done, and there is something to be said for that.”

In the global confusion that has marked the weeks since Italy’s dramatic caseload escalation, the austere and sometimes invasive measures imposed on compliant populations by China and some of its closest East Asian neighbours seemed to many like the best way to stop the spread.

Much has been made of the community “discipline” in South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong, which all sprang into action early and applied strict measures to flatten — or at least slow — the curve of new cases and allow their health systems to cope.

Those governments have been lauded for early implementation of mass testing, aggressive contact tracing, border closures, strict quarantine and social distancing that helped curb the initial spread of the virus, even though all four are now battling larger second waves.

More than 780,000 Singapore residents have downloaded the Bluetooth-enabled TraceTogether app, permitting the government to track and timestamp their every movement so they can identify who has had prolonged contact with an infected person.

Gradually, though, governments are realising that if measures to address the epidemic are to be sustainable, they must be culturally appropriate to the population being asked to comply. Scott Morrison said as much on Monday when he announced an unprecedented package of measures he described as “uniquely Australian solutions to deal with the unique Australian challenges we face here”.

Australia and Britain have imposed progressively stricter social-distancing and quarantine measures as caseload numbers have increased and voluntary policies have proven ineffective in keeping people out of pubs and off the beach.

Both governments are reporting a slowdown in infection rates but are also facing rising public pressure over heavy-handed tactics to enforce the new measures.

“There is no point trying to do something that’s not within the bounds of social acceptance,” Franks says.

“If you put people in lockdown and 20 per cent defy the directive, is that better or worse than having a more relaxed approach like Sweden but having 95 per cent of your population adhere?”

Of all the disparate approaches — each one flawed in its own way — a common thread emerging globally is the critical importance of early assessment and control to avoid the virus getting out of hand.

In the US, where the administration spent weeks downplaying the crisis and dragging the chain on testing and quarantine, President Donald Trump said this week that if they could contain the death toll there to 100,000 people or less, then “we all together have done a very good job”.

In the US 188,172 people have been infected — far eclipsing infections in both China and Italy — though far fewer (3899) have died.

Incredibly, some nations are still refusing to take any action at all, even as global coronavirus infection rates climb inexorably towards a million.

In the former Soviet state of Belarus, President Alexander Lukashenko ridiculed social-distancing measures this week as “psychosis” and advised his countrymen and women to drink vodka and take saunas to remain virus free.

Across Southeast Asia, varying degrees of government action — from border closures to emergency measures and full lockdowns — have had mixed results.

Singapore — among the quickest to react to the pandemic — has one of the world’s lowest mortality rates at just 0.34 per cent, while Indonesia — which was slow to test and adopt quarantine measures — has about a fifth of the region’s COVID-19 cases (1677) but almost half of its deaths (157).

India’s snap lockdown of its 1.3 billion population last week caught out hundreds of thousands of out-of-work Indian migrant workers who have been forced to walk hundreds of kilometres from India’s cities back to their villages.

In South Africa, President Cyril Ramaphosa has confined everyone to their homes in a total lockdown that has been criticised as impractical and even harmful for those in crowded townships.

It is unclear whether low infection rates across the African continent — just 5431 confirmed cases — is a result of low mobility or low testing. But there is little doubt the virus will cause a humanitarian catastrophe if, or when, it takes hold there, just as it will in the sprawling refugee camps of Bangladesh, Europe, Africa and the Middle East that now house 26 million people.

As things stand, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong remain the gold standard for managing the virus.

But Gregory Gray, professor of emerging infectious diseases at the Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, says while those countries should be admired for their early intensive efforts, it should also be recognised that their measures have been “very costly” to their economies and to personal freedoms.

“I think policymakers and public health officials are forced to base their interventions on an understanding of their national resources and their people,” Gray told Inquirer. “To do nothing is great folly. To do too much may also later be viewed as a mistake.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout