Coronavirus’ sickening consequences

Few sectors of the global society are immune to the impact of the coronavirus.

With skittish sharemarkets and the coronavirus for the first time notching up more new infections outside China than in, Australia has to contend with a radically uncertain global outlook — plus a unique economic challenge.

And as the rest of the world realises just how enmeshed its prosperity has become with China’s, Xi Jinping, for all his power and personality cult, is coming under pressure to get industry going again now the virus appears in retreat on the mainland.

On Thursday Scott Morrison trumpeted the preventive success of Australia’s early ban on travel from China while acknowledging the heavy costs of economic disruption, but he said public health had to be paramount and extended the ban, which is bound to punish national revenue.

“We’re effectively operating on the basis that there is (already a coronavirus pandemic),” the Prime Minister said. “We’ve got ahead, we intend to stay ahead.”

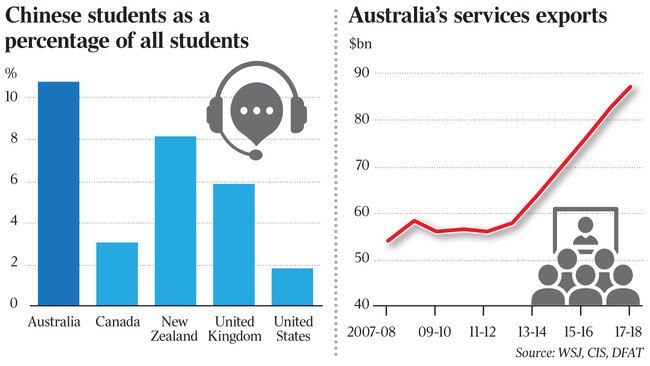

The government has signalled the long sought-after budget surplus may evaporate, and it will be acutely conscious of the outsize presence of tourists and Chinese students in the country’s service exports. These have expanded more than 60 per cent in the past decade, and two big reasons are aggressive university recruitment in China and a mainland tourist love affair with Australia.

China tourist boom

In 2017-18, we welcomed 1.42 million visitors from China, our No 1 source country and a market with plenty of dramatic growth potential, absent plague or other shocks.

Inbound tourism spending hit a new high of $22.6bn last year, and international student income rose 13 per cent to reach $39.9bn; again, China was the No 1 market.

Other sectors, such as minerals and resources, are not exposed in the same way but businesses of every stripe are linked to Chinese supply chains that have stocked inventories and filled the shelves.

Innes Willox of industry lobby Australian Industry Group flagged the problem last week. “Ai Group members say they are often getting no response when they contact Chinese suppliers — they’re simply not at work or unable to get to work,” he said. “The hunt for alternative supply and markets is well and truly on.”

And not only in Australia. Larry Fink, boss of the world’s biggest fund manager, BlackRock, has been reported as saying companies around the world are “asking about supply chains and the dependency on one location, China … I do believe there’s going to be a review of supply chains at every company in the world.”

But nowhere else is as financially dependent on the supply of Chinese students as Australia, and if there’s thought of some kind of review, it’s masked by the immediate crisis: the masters courses in business and management favoured by this market are due to start and at least 90,000 fee-paying students are still offshore.

Elements of the international education industry have pushed the government to ease the travel ban and allow some of these students into the country. The elite Group of Eight universities, where 60 per cent of the Chinese students stranded overseas are enrolled, said on Thursday it was “not its place to request any lifting or partial lifting of this ban, and (it) has not attempted to do so”.

“We know the government is at all times acting on the latest and best possible medical advice,” Go8 chief executive Vicki Thomson says. The group says it is concerned about the “many of whom we know feel vulnerable and upset. The Go8 sees this as a student welfare issue first and foremost and that is already driving forward logistics and planning to how we can have our students into their on-shore study as quickly as possible when the ban is lifted.”

If the Chinese students who are overseas do make it to Australia to start or continue their studies, the universities will not suffer much short-term financial damage, even if the students miss semester one and are refunded those fees. The big risk is that bad publicity about the situation will damage Australia’s reputation in China as a quality education destination, and students considering coming here next year decide to go elsewhere.

To manage the reputation risk the University of Melbourne has joined a clutch of others with less valuable brands to compensate students for the extra costs they are incurring, including getting to Australia using the travel ban work-around of two weeks’ quasi-quarantine in Southeast Asia and other third-country stopovers.

Melbourne’s pitch is worth up to $7500, Western Sydney University will pay $1500 towards these students’ costs and the Australian National University, with 4000 Chinese students caught by the ban, has told them that if they’re not able to be on campus by the end of next month they can still earn full academic credit by taking courses remotely at no cost.

Most universities with large numbers of Chinese students have extended the deadline for them to be on campus and beginning first semester studies. Most also offer online courses to students who can’t get here in the hope that will tide them over until they arrive. Then, if they do arrive later this semester, there are plans for intensive courses to help them catch up. Melbourne is offering a designated mentor to assist each student.

“Universities have been in touch with every student who has been affected, offering their support and reassurance,” Universities Australia chief executive Catriona Jackson says.

Among the students with big Chinese student populations, only the University of NSW has specifically said that students who can’t make the last starting date for the first term, Friday, are advised to defer until term two. UNSW has the advantage of a three-term academic calendar (as opposed to the two semesters at most universities), which means its next study period begins in June, well before the start of the year’s second semester at other institutions.

Reliant on students

One positive for universities is that more and more students are arriving through third countries such as Malaysia, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates, which continue to allow direct flights from China. Students stay there for their two-week quarantine period, then fly to Australia, aided by packages offered by travel agents and education consultants.

It’s estimated that up to 10,000 students of the 90,000-odd stranded in China could reach Australia this way. Last Friday and Saturday alone, 1500 Chinese students entered Australia by the third country route.

But how did it come to this?

Warnings were ignored, according to sociologist Salvatore Babones, an adjunct scholar with Sydney’s Centre for Independent Studies and an American with China expertise. In August he published a CIS booklet documenting our over-reliance on China, something that was not news but that he tackled with a rare directness.

“Australia’s universities are taking a multi-billion-dollar gamble with taxpayer money to pursue a high-risk, high-reward international growth strategy that may ultimately prove incompatible with their public service mission,” he wrote. “Their revenues have boomed as they enrol record numbers of international students, particularly from China.

“As long as their bets on the international student market pay off, the universities’ gamble will look like a success. If their bets go sour, taxpayers may be called on to help pick up the tab.”

Babones estimates that 20 per cent or more of revenues at the UNSW, the University of Sydney and the University of Technology Sydney comes from Chinese students. The Australian has estimated that 10 leading campuses face the loss of $1.2bn in fees from about 65,800 students at risk of cancelling their first semester courses because they are stranded in China.

In an interview this week with the Digital Financial Analytics video channel, Babones said: “Australian universities have become more dependent on Chinese students than any universities in the world outside China itself.” He said the American institution with the most Chinese students was the University of Illinois; it had less than 6000 compared with about 20,000 at Sydney University, where Babones teaches.

“The University of Illinois thought that its 5700 Chinese student exposure was so enormous, was so risky, that it took out an insurance policy with Lloyds of London against a scenario exactly like this (virus outbreak),” Babones told his interviewer.

“If the University of Sydney, University of NSW, the University of Technology Sydney had taken out insurance when I warned them six months ago, they would be sailing through this crisis.”

On a vastly bigger scale, China’s President Xi also faces a conundrum of competing risks.

Deepening economic damage from the COVID-19 outbreak is forcing the leadership to confront an agonising decision: when to ease quarantine restrictions that are strangling growth, even as they help contain the virus’s spread?

Business executives and some local leaders are becoming more vocal about the need to streamline rules to reopen factories and get workers and supplies moving again in many parts of the country where activity remains at a standstill. But many local officials fear doing so could risk a resurgence of infections, prolonging the outbreak and putting their jobs on the line. Many privately complain that Xi has put them in an impossible position, demanding they keep growth on track while also ensuring the virus doesn’t spread.

In an address to the 25-member ruling politburo this month, Xi instructed party members to wage a “people’s war” against the outbreak. Then, he said China must adhere to development targets, which call for doubling the size of China’s economy in the decade through 2020 — a goal officials say requires annual growth of at least 5.5 per cent this year.

Economic turmoil

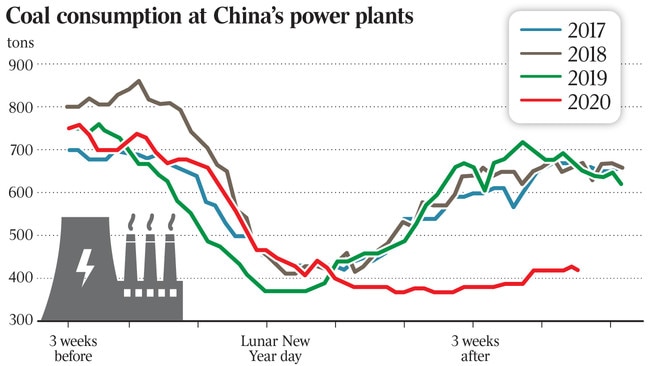

Despite Xi’s displays of confidence, the economy is fast weakening. Factories remain idle and consumption and investment have plunged. Average coal consumption at major power companies was about 40 per cent lower from a year earlier in the week through February 25, Goldman Sachs says. Home sales were one-quarter of the seasonal norm, it says, and demand for steel was about 50 per cent its normal rate in the past three years.

Using migration data from map-and-search company Baidu, Asia-headquartered financial services group Nomura estimates that a little more than a third of the people who left cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen for the Chinese Lunar New Year in late January and early this month have returned. By the corresponding period last year, nearly all had. Migrant labourers make up about 40 per cent of China’s workforce and are needed for manufacturers to resume production.

In some places, authorities have shut public transport and locked down residents. Even some cities far from the epicentre have been allowing residents outside only every few days. Hundreds of millions of people in China are in lockdowns of varying degrees.

Some sectors are calling for urgent help.

“We almost closed all our property sales offices overnight, and all sales have stopped,” reads a recent letter to the government in Jiangxi province, in southeastern China, from the Jiangxi Property Association. Its members, many of them private developers, “face huge financing pressure and are finding it hard to resume business”, the group says.

China Baowu Steel Group, the country’s largest steel producer, has warned that first-quarter profit will drop as much as three billion yuan, or roughly $US428m ($650m), because of disruptions from the epidemic. That would mark a 14 per cent decline from its profits in the same period of last year.

“Market demand has dropped,” says Zhang Jinggang, vice general manager of the group, at a forum on February 22. “Inventories are piling up faster than expected.”

Foreign companies such as Apple, Deere & Co. and car-parts maker American Axle & Manufacturing also have warned about softening sales in China. A mid-February survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in South China shows that more than 76 per cent of its 399 respondents believe their revenues this year will be hurt by the viral outbreak.

Some analysts are predicting zero or even negative Chinese growth in the first quarter, a direr forecast than a month ago, when the outbreak started to spread quickly. The slowdown is calling into question the leadership’s insistence that China can meet its economic targets this year.

“Propaganda can’t move mountains,” writes Zhang Anyuan, an economist at CFC Financial, a Chinese securities firm, in a February 24 report. Zhang is among the experts who think first-quarter growth could come in at zero or worse.

“Based on the seriousness of the economic losses in the first quarter, adjusting and downplaying growth targets would be understandable and acceptable to the people,” he says.

Additional reporting: Bernard Lane, The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout