Coronavirus: Nowhere to hide from the spread of panic

The world faces far more than a health emergency with COVID-19.

The dilemma for the government is finding the right balance between keeping people safe and informed without destabilising the economy or eschewing the international co-operation that will be essential if COVID-19 transmission is to be slowed and its effects minimised. This will require difficult trade-offs, evidence-based risk management, openness about a pandemic’s likely impact and prudent preparation for potential worst-case outcomes, a point Scott Morrison acknowledged when announcing the activation of his emergency response plan.

The silver lining of any crisis — and COVID-19 certainly qualifies — is that it provides opportunities for leadership and reform of pandemic risk management. Both are needed as COVID-19 casts a lengthening shadow over just about every area of policy from health, industry and employment to finance, education, tourism, sport, agriculture and national security. The crisis won’t be over quickly. Full-blown pandemics take two to three years to run their course, with peak illness typically occurring in the first year. The first three months are critical to determining their severity. But whatever we do in Australia won’t have a material effect on COVID-19’s global impact because the virus is an equal opportunity germ that infects humans without regard for borders, ethnicity, race or sex.

The immediate problem is understanding how serious the coronavirus emergency is likely to be, a medical uncertainty compounded by the difficulty of predicting people’s behaviour when driven by fear, and the efficacy of the international response. Despite the government’s best attempts to stay on top of the rapidly evolving crisis and keep the public informed, there are many misperceptions about the nature of the virus, what a pandemic means, why they occur and what should be done to mitigate the effects since containment is unlikely.

COVID-19, or more accurately SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) is similar to the flu (influenza) but is caused by a different virus. Both are infectious respiratory illnesses. Virtually all of us have had exposure to the flu, which normally results in nothing more than a bad cold, as leading virologist Ian Mackay observed last week. But previous exposure to the flu provides little natural immunity to COVID-19 so infection can result in serious illness or death.

Predicting the number of deaths can only be a guesstimate based on an assessment of several linked factors, the most important of which is the virulence of the virus, arrived at by calculating the percentage of infected people who won’t survive. Medical experts still don’t know for sure how virulent COVID-19 is, for two reasons. Most of the data comes from China and there are questions about its reliability. And the solid data we do have is inconclusive. The fatality rate in Hubei, the province most heavily infected, is between 2 per cent and 4 per cent. But in other parts of China it’s as low as 0.7 per cent. If the global average turns out to be at the higher end of this range, deaths could be measured in millions rather than thousands.

Another unknown is how many people will be infected. This is impossible to determine since we don’t know how rapidly the virus will spread before it peters out or an effective vaccine is developed, which seems at least 12 months away. COVID-19 carriers can infect others before they show symptoms themselves, making it more difficult to control the spread. Slowing the speed of transmission is vital because it provides time to adapt, marshal scarce medical resources and reduce the number of infections and therefore deaths.

Pandemics aren’t cyclical or predictable and they are not infrequent. There have been 10 influenza pandemics since the early 18th century and three in the past 100 years: in 1918, 1957 and 1968. These historical cases provide valuable clues as to how this health emergency may evolve. All were caused by significant mutations in one strain of the influenza virus. The 1957 Asian flu pandemic killed one million to two million people and lasted for two years, as did the 1968 Hong Kong flu, which killed three million to four million people worldwide.

The really big one was the Spanish flu, the deadliest in recorded history, which is estimated to have caused the deaths of 50 million to 100 million people between 1918 and 1920, more than were killed in World War I.

Could this happen again? It’s possible but unlikely because of the unique circumstances of the Spanish flu and vast improvements in international co-operation, pandemic management, our knowledge of infectious diseases and other medical advances. Normal seasonal flu kills between 290,000 and 650,000 people globally every year and most people who contract COVID-19 will recover after experiencing typical flu-like symptoms lasting three to five days. About 80 per cent of China’s reported cases have been mild and 14 per cent severe. Only 6 per cent of those infected have become critically ill, most older people with weaker immune systems.

Flu viruses are not the only cause of infectious disease pandemics, nor are they the most virulent. The first recorded pandemic was a severe outbreak of probable typhoid fever that decimated the inhabitants of Athens while the city was under siege by Sparta during the Peloponnesian War (460-404BC). The Black Death (1346-53), perhaps the most infamous pandemic of all, was a bubonic plague that laid waste to much of the known world, reducing Europe’s population by a third and killing as many as 75 million people globally. In modern times HIV-AIDS, which destroys human immune systems, continues to take a deadly toll having killed 36 million people since its emergence in the early 1980s.

Mortality rates for flu pandemics pale into comparison with some other infectious diseases. Most people infected with HIV-AIDS eventually succumb to the disease. Up to 90 per cent of those who contract the Marburg virus and the Zaire strain of Ebola, both haemorrhagic fevers, die. This compares with a 1.9 per cent mortality rate for the Spanish flu and the relatively low fatality rates ascribed to COVID-19.

For all our medical and public health advances the microbes seem to be gaining the upper hand as they continue to evolve and mutate. Infectious diseases remain the No 1 killer of humans worldwide. Although they have been around for thousands of years, there has been a surge in the number of previously unknown infectious agents since the 80s. More than 30 have been identified, including HIV-AIDS, rotavirus, Ebola, SARS and the H5N1 bird flu. Some old scourges thought to have been defeated have spread or re-emerged, sometimes in more virulent form such as the plague, cholera, dengue fever and tuberculosis. About 80 per cent are zoonotic pathogens, microbes that originate in birds and animals and are then transmitted to humans.

Their recent spike has been driven by several difficult-to-reverse environmental, social and behavioural triggers that alter the microbial balance between animal and human populations. As their natural habitats are destroyed, wild animals are coming into more frequent contact with domesticated animals and humans, infecting them with diseases to which they have built up resistance. H5N1 bird flu probably originated in wild ducks, which then infected poultry before jumping the species barrier to humans. Pigs are particularly susceptible to avian and mammalian viruses. Along with chickens, both can serve as a “mixing vessel” to produce a more virulent and transmissible strain of the original virus. Higher population densities and the growth of large cities in the developing world, along with rapid growth in international travel, have made it more difficult to control the spread of disease once outbreaks occur.

Southern China historically has been an incubator for flu viruses due to its high population density and agricultural practices, with people living in proximity to domesticated animals and flourishing wild animal markets. The Asian and Hong Kong flus originated in China, as did SARS. It’s hardly surprising that COVID-19 is out of China too, given the rapid increase in people, pigs and chickens. In 1968, when the Asian flu became a pandemic China had 790 million people, 12.3 million chickens and 5.2 million pigs. Today, it has 1.4 billion people and more than 5.2 billion chickens. Before last year’s swine flu and subsequent culling decimated their numbers, China’s pig herd had swelled to 440 million, half the world’s pig population.

The biggest behavioural challenge for government and business will be dealing with the fear pandemics inspire. For all our supposed rationality and access to unprecedented levels of information and knowledge, fear of disease is still deeply embedded in the human psyche. This frequently results in irrational or selfish behaviour that can worsen the social and economic impact, as Australians found out this week when panicked buyers stripped supermarket shelves of toilet paper, sanitisers, disinfectant and food.

Nearly 700 years ago, Sienese chronicler Agnolo di Tura observed of the Black Death that fear froze out every caring instinct. “Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another,” he wrote. “And no one could be found to bury the dead for money or friendship.” The World Bank concluded behavioural effects were responsible for as much as 80 per cent to 90 per cent of the total economic impact of SARS and the H1N1 flu epidemic of 2009. And as business commentator Alan Kohler points out, this is the “first social media pandemic”. It would not take much for social media to become an echo chamber for misinformation and fake news about the virus, spreading fear across the world in an instant.

While there are many unanswered questions about the impact of COVID-19, five conclusions can be drawn.

First, although we should not have been surprised that a coronavirus would wreak havoc on the world, many governments are ill-prepared. This is not a “black swan” — an “unknown unknown”, or improbable event. A more apt metaphor is Xi Jinping’s “grey rhino”: a “known unknown”, or highly probable, high-impact yet neglected threat. In other words, we should have seen this coming. The historical record clearly shows influenza epidemics periodically turn into pandemics.

Recent experience with SARS and several strains of bird flu ought to have prepared us for COVID-19, even if its timing and specific characteristics were unknowable. The reality is that there will be more flu and other infectious disease pandemics after COVID-19. They are likely to occur more frequently, with equal or even greater impact, as the tyranny of distance gives way to the perils of proximity in a world ever more mobile and connected.

Second, Australia is better equipped than most countries to manage COVID-19 because of our world-class medical system and prudent measures put in place by previous governments to deal with infectious disease outbreaks. But even though we are an island continent, with strong border protection and natural physical barriers to disease transmission, no man or woman is an island in today’s microbial environment, to paraphrase poet John Donne. As medical experts concede, almost everyone will be exposed to this virus over time as we move from containment to mitigation. The real worry is how the developing world copes with the pandemic, which will largely determine the severity and duration of the health fallout. If COVID-19 entrenches itself in Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America then this will become an even more challenging year.

Third, pandemics are more than just health emergencies, inevitably becoming international security crises because of their wide-ranging consequences. Yet in our first and only national security strategy written more than seven years ago, there is only a cursory mention of pandemics. And they don’t feature in the list of key national security risks despite the safety and resilience “of the population” being a declared national security objective. The government would be wise to rectify this omission by rewriting and updating the national security strategy.

Fourth, the biggest impact may be on China’s political stability and economic prospects. The Year of the Rat is shaping to be Xi’s “annus horribilis”. His claims to global leadership, already fraying at the edges because of a multitude of recent domestic and international setbacks, are under real pressure because of mounting criticism at home and abroad about his handling of the coronavirus crisis. The country is headed for the lowest economic growth in a generation exacerbated by the trade and tech wars with the US, neither of which has been resolved despite the signing of an interim phase one trade agreement in January. Global supply chains had begun to decouple before COVID-19 struck as a result of US pressure on countries to exclude Chinese technology from their ICT networks. Larry Fink, head of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, believes China’s dominant position in global supply chains will come under renewed scrutiny as the virus makes companies realise that over-dependence on China is a potential liability. Manufacturing output has plunged and agriculture is also in trouble. Farmers in Hubei province — the epicentre of the COVID-19 outbreak — are in a “very stressed situation” because of a severe shortage of feed according to Hubei’s poultry association.

Fifth, the economic impact of a pandemic is almost always underestimated in its early stages because there are so many variables and uncertainties. This is especially so in today’s hyper-connected global economy where trillions of dollars move around the world at warp speed and just-in-time supply chains lack resilience and redundancy. If the chain is broken the consequences are rarely confined to a single product or country. We know SARS cost affected economies $US40bn. But this was a much more contained epidemic affecting mainly Asian economies. Moreover, only 8000 people were infected compared with COVID-19’s nearly 100,000 infections. And China was not, then, the world’s manufacturing engine responsible for 40 per cent of global growth. With Hubei still in lockdown, and the Asian giant’s economy in trouble, it’s an even-money bet that COVID-19 will trigger a global economic recession. Even if it doesn’t, COVID-19 is shaping to be the most economically damaging and politically disruptive virus since the Spanish flu, and it will have a disproportionably negative effect on Australia because of our China dependence.

Alan Dupont is chief executive of geopolitical risk consultancy the Cognoscenti Group and a non-resident fellow at the Lowy Institute. He has written and lectured extensively on pandemics.

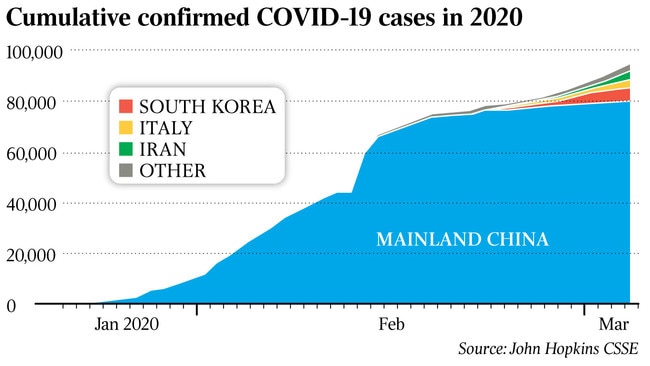

When China sneezes the rest of the world catches a cold — literally, it seems. What began as a minor flu-like outbreak in Wuhan city has morphed into a full-blown international health crisis that has roiled financial markets, raised the spectre of an economic recession, disrupted global supply chains and adversely affected the lives of hundreds of millions of people. The world stands on the brink of a full-blown pandemic as the COVID-19 coronavirus moves out of China infecting more and more countries. Misplaced optimism that the disease would be contained risks being replaced by unfounded panic that could fuel, rather than arrest, its momentum.