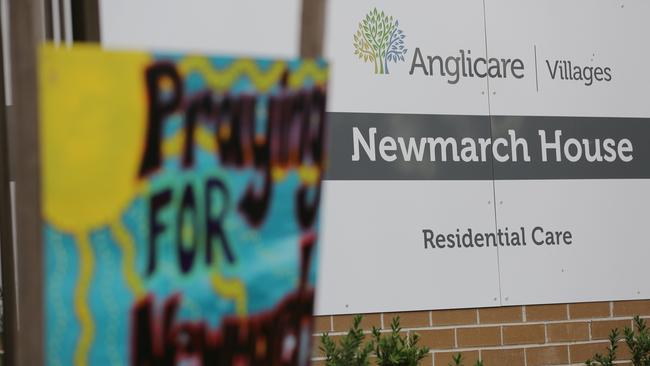

Coronavirus: Newmarch House nightmare exposes fatal flaws

We are deluding ourselves over our success in our handling of this pandemic.

They were the collateral damage of a system that herds old people together in institutions that we call care.

The outpouring of praise for aged-care workers by federal Health Minister Greg Hunt on Wednesday is all very well, but this is no substitute for the immediate questions that must be asked about Sydney’s Newmarch House and the whole model of an institutional system that has been found wanting.

As I know from bitter experience, the relatives of these people are probably too numb with grief and misplaced guilt to ask the questions that must be asked right now. However, the public deserves to know why the residents were not vacated from this facility and placed in isolation in hospital as soon as the first case was diagnosed. We know most of the intensive care wards around NSW are empty of COVID-19 patients, and a surge workforce at Newmarch was put in place only after three residents had already died.

Nursing infected patients within a hospital is very different from within a nursing home, where barriers were apparently so lax that infected people were being moved through common areas. Why were the families of residents kept out of communication, and why were those who tested negative not allowed to be removed by relatives, even to their own homes?

When the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission finally threatened to take away the institution’s licence, I, like many others, thought: “It’s about time.”

All these questions must be answered. However, blaming just one system failure in one institution or one set of bureaucrats is not going to be the answer here. The real underlying culprit is the aged-care system itself. We have come to rely too much on the institutional model of aged care in Australia. We have comforted ourselves with the idea that care in an institution equals real care. Blithe reassurances by politicians and the sector that “overall” they did a good job just don’t cut it.

I have had multiple experiences with institutional aged care. My parents were in not one but three institutions across a period of four years. All of these institutions were top quality, with all the latest facilities, kind staff, with reasonable staffing ratios. Of course, families always have to fill in the gaps, which was not a problem. Most of these places welcome the families and the best institutions regard their job as helping the family rather than the other way around. My husband and I even moved in for a week when my dad was dying, and we fed and nursed him ourselves. However, in every single one of these institutions there were problems, and none was the result of neglect or abuse but simply a result of the institutional mentality.

An aged person’s welfare is totally subsumed by the necessities of institutional life and its basic routine. In our experience, this led to my parents — married for 68 years — being separated in the first institution they were placed, simply because they had different needs. That is the way an institution is efficiently run, but needless to say they were moved to a place where they were not apart.

I came to see that long-term institutional care is fundamentally damaging to old people. First, their physical health is always precarious, and they are constantly exposed to some level of infection. No matter how clean the institutions are, minor infections — typically things such as eye infections — spread like wildfire and major ones are common, especially in large institutions. There are often minor epidemics. While my parents were in the last of the three places, there was a gastro outbreak. However, fundamentally, the major problem with institutional care is the subtle mental effect of isolation from a normal family and social milieu. Many experts have pointed to this.

Aside from the effects of sudden removal from their home where they have lived for decades, everyone in aged care is old. Think about it. The mostly young female staff do not interact with the residents in the same way as people would interact outside the institution. There is no real freedom.

The language we use betrays this. We speak of putting people intocare, and there they will stay. The principle of “ageing in place”, the preferred Australian institutional model, is somewhat ironic since the place is where they do indeed stay — with a few outings.

They mentally stagnate. In short, there is no chance to experience any normal life or social interaction — one of the most important bulwarks against progressive dementia.

So what can be done in a society where people are very loathe to look after their aged parents themselves? In 2018, a Flinders University-sponsored study found that smaller group housing produced much better physical and mental outcomes. This is pretty consistent with other overseas research and practice. However, the first thing is to give people who are generous enough to look after their own parents the proper support and incentives. Countries that have the most innovative models of aged care have recognised the fundamental flaws in an institutional model. In many European countries, including France and Germany, which have family unit taxation systems, the elderly in a family are counted as double tax deductible. In other countries, respite care, both in the home or in a small institution, is also favoured.

Australia is behind the times in pushing a large institutional model of care for the aged. However, unfortunately, social workers and medical staff are fixated on it as the only outcome. I will never forget the bland fatalism of the doctor and social worker at the hospital where my mother was languishing long after a broken shoulder had healed, telling me that taking Mum home was not a good idea — because “after all, she is institutionalised now”.

During this pandemic, “We are all in this together” has been the morale-boosting slogan du jour. However, while we are patting ourselves on the back for our success in handling the pandemic, people in aged care have suffered this terrible illness and died alone.