Coronavirus: How the lost generation will turn out

More than three-quarters of the world’s 1.5 billion kids aren’t in school right now. Here’s how their future will pan out.

In the streets of Amsterdam, children spend the “corona holiday” whizzing around on scooters; their peers in Paris are mostly stuck at home with video games; those in Dakar look after younger siblings. The one place they are not is at school.

More than three-quarters of the world’s roughly 1.5 billion schoolchildren are out of school, according to UNESCO, a UN agency. In most of China and in South Korea they have not darkened school doors since January. In Malta and California they will not return before September. This global locking of school gates is unprecedented in scope, duration and likely consequences.

Schools have always strived to remain open during wars, famines and even storms. Their prolonged closure is costly. Most immediately it stands in the way of parents’ productivity. More worrying is the long-term harm done to children and their prospects. Closures stymie the learning and development of all kids. No amount of helicopter parenting can make up for the influence of peers and thought-through lesson plans.

Closures especially affect the poorest and the youngest school-goers. Those less likely to have access to three meals a day, an internet-enabled computer, highly educated parents, an available teacher and a safe, quiet space to study will fare worst.

And if eight-year-olds’ learning stops until spring (northern autumn), as it will for some, they could lose nearly a year’s maths attainment, according to first estimates. Without interventions the effects could last a lifetime.

For these reasons Singapore in 2003 cut its month-long June holiday by two weeks to make up for a fortnight of school closures during the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Even short interruptions hurt performance. In the US third-graders affected by weather-related closures do less well in state assessment exams. French-speaking Belgian students affected by a two-month teachers’ strike in 1990 were more likely to repeat a grade, and less likely to complete higher education, than similar Flemish-speaking students not affected by the strike.

West Africans recall the devastation caused by longer shutdowns. Today’s older schoolchildren will remember how school closures during the Ebola outbreak in 2014 led to an increase in unplanned teen pregnancies and in related school dropouts.

The digital gap

The difficulties faced by today’s schoolchildren in the rich world may seem trivial in comparison. In fact they, too, are serious and life-changing. The rich world has no modern precedent but a 2017 paper by Keith Meyers, of the University of Southern Denmark, and Melissa Thomasson, of Miami University, on a polio epidemic in 1916 in the US made the lesson clear: closing schools hurts kids’ prospects. The younger ones leave school with lower achievements than previous cohorts and the older ones are more likely to drop out altogether.

Of course in 1916 there was no videoconferencing. Today nearly nine in 10 affected rich countries provide some form of distance learning (compared with only one in four poor countries). But this too can serve to highlight inequalities. In Britain more than half of pupils in private schools are taking part in daily online classes, compared with only one in five of their peers in state schools, according to the Sutton Trust, a charity.

In the first weeks of the lockdown some US schools reported that more than a third of their students had not even logged in to the school system, let alone attended classes. Meanwhile, elite schools report near full attendance and the rich have hired teachers as full-time private tutors.

Ashley Farris, an English teacher at KIPP high school in Denver, Colorado, says several of “her” kids are virtual truants. Her school worked hard to get students computers and Wi-Fi access, but the digital gap is only part of the story. Some have had to get jobs to make up for the wages their parents have lost. Others must look after younger siblings.

During the past century, as global attendance at primary schools has risen from 40 per cent to 90 per cent, schools have been engines of social mobility. Closures in Britain could increase the gap in school performance between kids on school meals (a proxy for economic disadvantage) and those not, fears Becky Francis, from the Education Endowment Foundation, another charity.

During the past decade the gap, measured by grades in tests, has narrowed by roughly 10 per cent, but Francis thinks school closures could, at the very least, reverse this progress. Fears are growing that the “summer learning slide”, which sees knowledge lost over the summer break, will become an avalanche for some. At least over summer, teachers are not on tap for anyone. In the current lockdown some students can still quench their thirst for education, not only with highly educated parents but also with teachers; others will have access to neither.

Some countries are better placed than others to withstand such pressures. The scale of pre-existing inequalities will be especially important. In places such as Denmark, Slovenia and Sweden the vast majority (95 per cent) of 15-year-olds have access to a computer at home, regardless of family background. In the US that is true for virtually all students in the wealthiest quartile but only three in four of those in the poorest. In Mexico it’s 94 per cent and 29 per cent respectively. To make matters worse, poorer kids tend to have more siblings to squabble with over the use of what devices there are.

Finland started distance learning only when it was satisfied almost every child would be able to take part. South Korea extended its school holiday to prepare teachers and distribute devices where needed.

Parents as teachers

Also important is how used students are to being given their own projects, says Andreas Schleicher of the OECD, a club of rich countries. “The real issue is if you’ve been spoonfed by a teacher every day and are now told to go alone, what will motivate you?”

In Estonia and Japan most students are used to “self-regulated activities”, and across OECD countries the proportion is nearly 40 per cent. But in countries such as France, Italy and Spain, such autonomy is rare.

Perhaps the biggest factor in exacerbating inequality in today’s circumstances is the parenting gap. In a recent poll by the Sutton Trust nearly half of British parents in middle-class professions were confident about home-schooling, compared with just over a third of working-class parents.

Since the 1970s, university-educated parents in the rich world have drastically increased the time spent with their children, including on homework. As better educated parents are able to devote more time to their children than less educated families, the “attainment gap” widens, particularly in early childhood. It has grown especially quickly in very unequal countries such as the US.

Ironically, primary schools in more egalitarian Scandinavian countries are reopening whereas in places such as the US and Britain pupils are left to their own devices at home. “Some five-year-olds will be home-schooling with parents while others might be left playing video games,” says Natalie Perera, of London-based research group the Education Policy Institute. Even in more egalitarian countries, however, the pain is not spread equally. At the Alan Turing primary school in Amsterdam, it quickly became clear that 28 of its 190 pupils could not take part in online classes. The school now opens its doors for 15 from this group three mornings a week and has found other ways to help the remaining 13, such as getting assistance from their neighbours.

“At first it felt like we were doing something illegal,” says headmistress Eva Naaijkens, “but how can you accept a situation where a number of children just drop out?” She calls for realism, estimating that her teachers can impart perhaps 40 per cent of the education they normally would.

That roughly tallies with the assumptions researchers in Norway have made to estimate the costs of closures to the economy. A “conservative” calculation by Statistics Norway estimates the country’s educational shutdowns — from creches to high schools — are costing its economy 1.7bn krone ($251m) a day. Most of that is the estimate of lost future income of today’s schoolchildren, who, they assume, are learning roughly half of what they normally would, and so are suffering a reduction in their “human capital”. The rest is lost parental productivity today.

The long-term cost

Another way to estimate the magnitude of learning losses — and gaps — now emerging is to dig into summer learning loss data. Across the holiday, young kids in the US normally lose between 20 per cent and 50 per cent of the skills they gained over the school year. This is a global problem but most studied in the US because of its long summer vacations.

Matthias Doepke, of Northwestern University, estimates that by the end of this northern summer the sizeable group of American children whose learning loss started when schools closed may have lost up to a year’s attainment. Since every year of education is associated with a rise in annual earnings of roughly 10 per cent, the consequences for those children become clear. “I fear we will see further inequality and less social mobility if nothing is done,” he says.

Social and emotional skills, such as critical thinking, perseverance and self-control, are predictors of all sorts of things, from academic achievement and employment to health outcomes and the likelihood of ending up in jail. And whereas older children can be plonked in front of a computer, younger ones learn far more when digital learning — whether reading an e-book or watching a video — is adult-supervised.

Primary school normally offers a crucial opportunity for gaps that emerged in early years development to start narrowing or at least to stop widening. That opportunity is now missing. For a glimpse of the cost to the unluckiest young children, consider the Perry preschool project of the 1960s, a study conducted in Ypsilanti, Michigan, that found a control group of young children from disadvantaged backgrounds who did not attend preschool suffered lifelong consequences.

Another concern is that reading gaps will widen. The downward spiral that comes with early reading difficulties is well established: when children fall behind they can become demotivated and read even less, dropping further behind. Poor readers are less likely to graduate from high school and at greater risk of ending up in a juvenile prison.

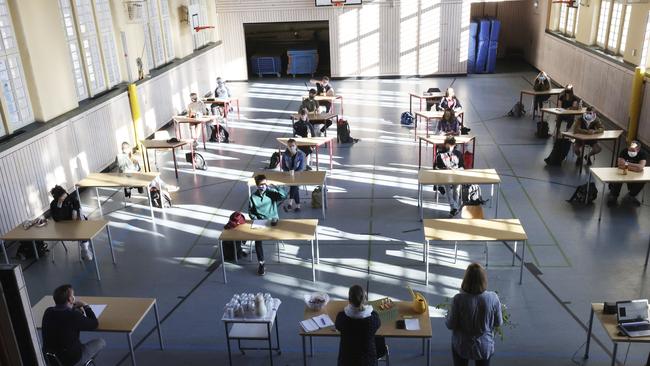

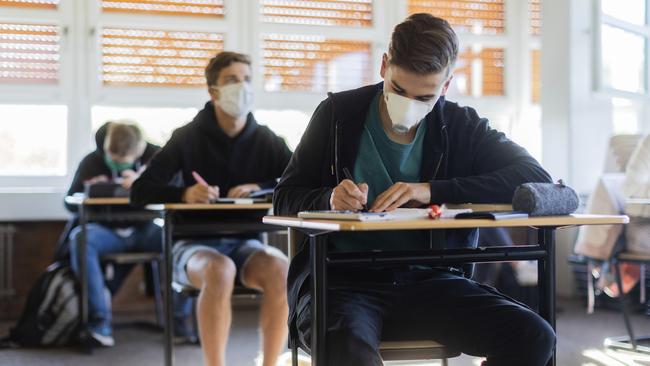

The other group to focus on is those facing critical exams, which may have a big impact on lifetime outcomes. Germany is reopening schools for final-year high school students who face exams in May and June. China has postponed its leaving certificate exam until July; South Korea has moved its university entrance exams to December. Several other countries, including Britain and France, have cancelled this year’s exams altogether. Grades are in part decided by teachers’ predictions of how a student might have performed. This further fuels fears of inequality, as some experts worry teachers unconsciously discriminate against less privileged children and give them unfairly low marks.

As well as letting final-year secondary students facing exams resume classes, Denmark has also reopened creches and primary schools. The decision to make a priority of the very young was driven as much by the realisation of how crucial this early stage of learning is, as by the childcare burden and perception that the risk of young kids getting or spreading the virus was low. Around the world many parents will be hoping their children’s schools too can safely reopen soon.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout