Coronavirus exposes the sum of all threats as our ‘national security’ is lacking

The COVID-19 virus particle is 1000 times smaller than the width of a human hair, yet it has wreaked chaos and will dramatically shift our approach to national security and supply chains.

The COVID-19 virus particle is more than 1000 times smaller than the width of a human hair, yet it has wreaked chaos across the globe and shaken the foundations of the world’s greatest powers.

So far Australia appears to be withstanding the pandemic better than most Western democracies. But the virus’s profound economic and human consequences will transform the way in which Australians view national security.

Before the crisis, Scott Morrison was being urged behind the scenes to recast the national security debate to include a clear-eyed assessment of the nation’s most pressing vulnerabilities.

Australia’s overwhelming reliance on imported medicines and fuel, its decimated merchant shipping fleet and hollowed-out manufacturing industry were among the identified priorities.

Now, in the age of coronavirus, the pressure will grow as taxpayers question why they are being forced to spend $80bn on the world’s most expensive conventional submarines when the country’s most pressing needs are surgical masks, hand sanitiser and hospital ventilators.

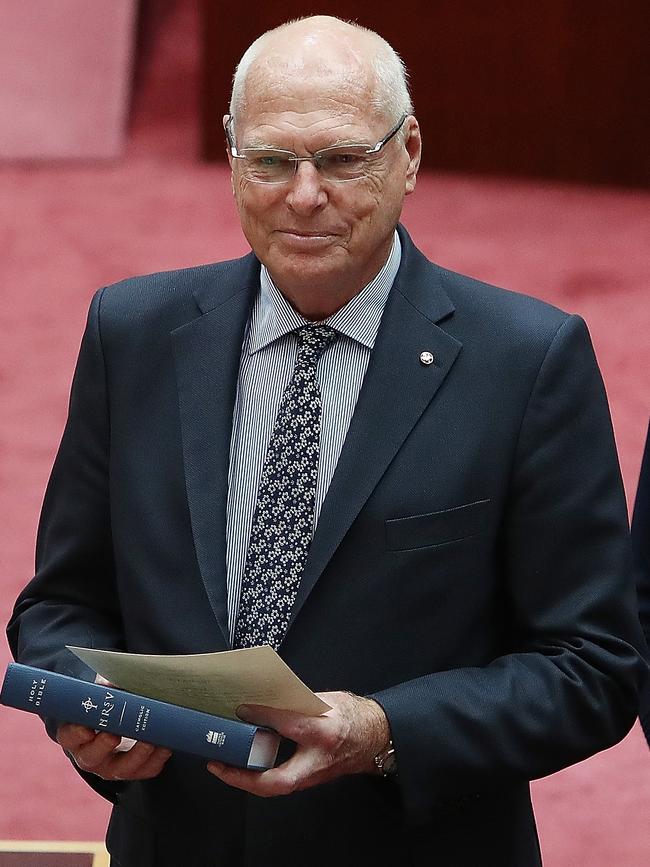

Liberal senator and former major-general Jim Molan has been quietly building support for the development of a new national security strategy, focusing on national resilience as much as military threats.

Liberal MP Andrew Hastie, the intelligence committee chairman and former SAS captain, is a strong supporter of the shift, along with Labor members of the committee Anthony Byrne and Mike Kelly.

More will join the debate as right-wing hawks find they have more in common with Labor-left protectionists than they may have thought possible.

Retired air vice-marshal John Blackburn has been one of the leading advocates for a more holistic view of national security based on “smart sovereignty” and trusted supply chains.

“We’ve got to accept that the price of not doing it is much higher than the lower cost of buying the cheapest thing,” he tells The Australian.

“When a crisis happens, the government and the community can get on and manage the crisis, and we’re not running around fighting for toilet rolls.”

The Institute for Integrated Economic Research, which Blackburn chairs, recently published a paper that identifies Australia’s 90 per cent reliance on imported medicines as a national security risk. It warns that the China-dominated supply chain for drugs and active pharmaceutical ingredients leave Australia’s medical supplies vulnerable to disruption.

And the Therapeutic Goods Administration’s medicines shortages list reveals that 58 drugs used by Australians are subject to critical supply issues, with more than a dozen added to the list in the past fortnight alone.

The retired RAAF officer also has been a key agitator on Australia’s fuel insecurity, railing against the lack of strategic reserves of crude oil and finished petroleum. According to Department of Energy figures, Australia has only 29 days’ worth of liquid fuel stocks at refineries and wholesale terminals — well under the International Energy Agency’s 90-day fuel security benchmark.

Energy Minister Angus Taylor recently signed an agreement allowing Australia to lease crude oil stored in the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which theoretically would be available to Australia in an emergency.

But the deal is widely seen as an accounting trick to appease the IEA. In a crisis, it would take between 20 and 40 days for the stored oil to get to Australia — even if the US allowed it and providing the sea lanes were open. The situation is compounded by the lack of any Australian-flagged tankers, or any other international ships, to deliver the precious cargo.

A 2018 study for the Maritime Union of Australia by respected shipping analyst John Francis found it would take 60 tankers working full-time to deliver the nation’s entire imported fuel supply, but the cost of such a fleet would amount to less than 1c a litre for motorists at the bowser. Says Blackburn: “We need to have smart sovereignty. We can’t be completely independent of global supply chains. But 90 per cent dependence on imported fuels and imported medicines is not acceptable in the world we live in today.

“When we come out the back end of this crisis, in the rubble of the economy and the rubble of the health system, when people are completely shocked, which direction will we all head towards?”

While Donald Trump has struggled to rise to the COVID-19 challenge, he has been quick to see its implications for his “America First” agenda, and his push to decouple from China.

“America will never be a supplicant nation,” the US President said this week as hospitals in New York and elsewhere in the country were overwhelmed.

“We will be a proud, prosperous, independent and self-reliant nation. We will embrace commerce with all, but we will be dependent on none.”

Across the world, global leaders are now looking through Trump-like eyes as nations fight for scarce supplies of personal protection equipment and lifesaving medical hardware.

Australian Institute of International Affairs president Allan Gyngell wrote this week that the economic and social shock of the pandemic “has done more to close borders, reverse globalisation, decouple supply chains and marginalise multilateral institutions than the most fervent efforts of the world’s populist nationalists”.

The Australian National University’s National Security College head, Rory Medcalf, says the reassessment of supply chains will be critical when the pandemic has passed.

Medcalf warns that Australians also will face fresh obligations as community members.

“We will think of security as holistic and inclusive — everyone has to contribute, including all levels of government, business and ordinary citizens,” he tells Inquirer. “We are finally realising that our security as a nation and a society is not just a problem for the professional security caste in Canberra but it matters to all of us, and all of us must contribute.”

A new non-military system of national service “should not be off the table”, Medcalf says, as Australia shifts to recovery, enabling citizens to contribute their skills and energy “to the sustainability and resilience of Australian society”.

Such a service could, across time, take over civilian tasks that increasingly have been thrust on the Australian Defence Force — including responding to natural disasters, such as the recent bushfires in our Black Summer — allowing the ADF to focus on its primary task of preparing for war.

“Right now, the government is literally giving — at a level nobody could have imagined — to the citizenry and the private sector to keep the nation going,” Medcalf says.

“That means there should be an expectation that we too will all be willing to give, in order to sustain and protect our country and therefore ourselves and our values.”

In Finland, which has a system of universal military service for men, national security is widely accepted to be an issue of personal responsibility.

The country’s shared border with Russia has fostered a doctrine of “total defence”, in which citizens, businesses and government institutions all play a role in safeguarding the society.

Norway and Sweden have similar systems, emphasising collective security and the engagement of all parts of society to safeguard the nation against outside threats.

Ross Babbage, a former intelligence and defence official and now nonresident fellow at the United States Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, says Australia could learn much from the Scandinavian countries as it considers the sort of country it will need to become after the coronavirus crisis.

“We clearly have to make our own judgments on what makes sense for Australia, but there is a lot we can learn from looking more closely at what has worked and what hasn’t in those countries,” Babbage says.

Hardening the nation’s critical infrastructure, including communications and energy systems, will also be important, he adds

“The bushfires demonstrated many of the weaknesses of Australia’s civil infrastructure in crisis situations. Power was lost for extended periods, communications broke down, emergency radio broadcasts failed, and communications between governments and local communities were essentially broken for extended periods,” Babbage says. “There is clearly a need to build a much stronger resilience into our critical infrastructure for multiple purposes, but certainly including bushfires.”

The horrific financial cost of coronavirus will have to be paid for across the economy, with the Department of Defence unlikely to be immune from post-pandemic belt-tightening.

Even if the government maintains its promised 2 per cent of gross domestic product funding for Defence, it will be 2 per cent of a much-reduced funding pool.

Inevitably, Defence’s mega platforms — including the Future Submarines and Future Frigates projects — will come under fresh scrutiny. The programs may have to be scaled back or delayed.

But, as Babbage warns, the post-pandemic world will be more fragile and dangerous.

Nation-states will fail economically. Competition for increasingly rare and precious resources will intensify.

And relations between the world’s superpowers will almost certainly worsen.

“Global tensions are not fading. In fact many of the conventional security challenges for the next five to 10 years look like becoming more severe,” Babbage says.

“This is not the time to contemplate serious cuts to our defence development programs. We really need to maintain those, and in fact we should go further in some key areas.”

Before the pandemic hit, Defence Minister Linda Reynolds was overseeing two related reviews by her department — a strategic update to the 2016 defence white paper and an updated force structure plan.

The authors of these reviews were grappling with a more militarily assertive China, as well as growing demands for Defence to respond to natural disasters at home and across the region.

With an even more constrained budget, and changed global circumstances, those reviews will have to be completely rewritten. Many will argue for a parallel assessment of broader national security questions to be included in their findings.

“It is time for a grassroots-up rethink,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute executive director Peter Jennings says.

The former Defence and government insider says the absence of a national security strategy and a national security adviser is making Australia’s pandemic response even more challenging.

While responsibility for the response lies within Peter Dutton’s Home Affairs portfolio, the Prime Minister, correctly, has been leading from the front.

“The question is: ‘Does the Prime Minister have the resources at his reach to deal with that?’ And I think at the moment the answer is no,” Jennings says.

“I would be appointing a national security adviser and developing a national security strategy and getting ready to rewrite the defence white paper as well.”

It is a sentiment Molan shares. But as a backbencher and sometime factional warrior, he has been careful not to push too hard on the issue for fear of jeopardising the project.

“I think it is critical to start the conversation on everything that Australia will be when we come out of this crisis, especially security, resilience and sovereignty,” Molan tells Inquirer.

“I can see that vision behind government health and economic policies at present. I am an advocate of a national security system for Australia and have been for years, but let’s wait until we can at least see the end of the crisis.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout