Coronavirus: Even glass-half-full optimists can do the maths

The genie is most likely already out of the bottle. If fewer than 100,000 Australians die, we will be doing well.

It’s the projected death toll that is most staggering. Indeed, that reality, and how profoundly it will impact on the Australian and global societies, is at the heart of the panic that has engulfed the planet.

Make no mistake: we are living through extraordinary times. And as one government MP said to me during the week: “We aren’t even at the end of the beginning yet.”

Doing the maths as to how many among us might fall victim to this virus is truly mind-boggling. We are constantly being told to listen to the experts. Hear what the medical professionals have to say. It is those same experts who say that the virus could easily infect between five million and 15 million Australians. Their assessment is that the genie is most likely already out of the bottle, and hopes of containing the virus such that it doesn’t spread so dramatically are wishful thinking.

Do the maths.

Politicians are hopeful that Australia’s infection rate can be slowed down — which is the so-called flattening of the curve. It’s not about containment. Rather, the aim is merely to spread out the time period during which so many of us catch the illness so that the hospital system can cope. That matters because exactly how well or badly the hospitals handle the crisis has a direct impact on the mortality rate.

If we do well, the mortality rate might match South Korea’s 0.7 per cent rate. In other words 7000 people die for every million who contract the virus.

While the government might want to stay glass-half-full and point to the fact that 80 per cent of people who are infected have only mild symptoms, that leaves one in five people who get it doing worse than that.

If between five million and 15 million Australians are infected, doing the best-case maths on the mortality rate to follow would mean 35,000-105,000 Australians will die from the coronavirus.

I have heard shock jocks play down the risks, pointing to how many Australians get cancer in their lifetimes and so on. But these figures are based on infections over the next six months, not over many decades.

What all nations are hoping to avoid is matching what has happened to Italy, where the virus is not only spreading rapidly but the mortality rate is closer to 7 per cent.

Do the maths.

If Australia suffers the fate Italy has, we will lose as many as 70,000 lives for every million infections. I don’t even want to do the maths on what that means if as many as 60 per cent of us get the virus.

Whether we do well by global standards, or badly, the corona-virus is going to be life-changing for all of us. The odds are most of us may know someone who dies from it. Perhaps someone close. Perhaps ourselves.

It is no wonder people are panicking. It is no wonder the elderly and the sick in particular are scared. And it is no wonder people want to trust their politicians to make the right decisions to minimise the pain.

We all hope our government succeeds.

And when we traverse from the best-case scenarios to the worst, it is clear that there are no good outcomes. Which is why the global economy is in meltdown as financial markets process the effect the virus is having and will have for a long time to come.

Australia has a natural advantage. Not only are we an island nation capable of easily shutting down our borders, as the Prime Minister finally did on Friday at 9pm. We are also behind the exponential growth rate of infections in other countries, meaning that we can watch what they do and how they react. Observing the differences to help us hopefully chart a more successful path than most. But is that happening? We will only truly know if our leaders got the decisions right many months from now. Possibly years.

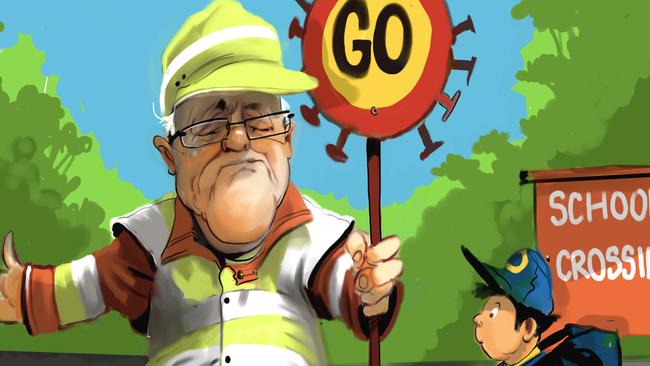

Right now the most contentious non-action is on schools. Scott Morrison has acted differently to most nations by leaving schools open. More than 100 countries have closed down their schools. While he tries to use Singapore choosing to leave schools open as a point of comparison, it’s not analogous. Singapore, which learnt a lot from combating the spread of SARS, has mandatory temperature checks at schools. Mandatory health checks. It enforces social distancing. Students and staff wear masks.

None of these things is happening here. Even teachers don’t wear masks as a mandatory protection. I spoke to a Singapore government official who said there was no way schools in his home country would remain open if the practices there matched the lack of safeguards in place here.

Another potentially bad decision by the government was not to immediately close down mass gatherings last Friday when the announcement was made. The argument was that organisations needed the whole weekend to get their affairs in order. The PM wanted to go to the footy on Saturday. Compare that complacency to the sudden decision to close our borders to foreign visitors in just 24 hours.

As it turns out, the Rugby Championships final in Sydney that Saturday saw a coronavirus contagion, which required the NSW Chief Medical Officer to order everyone who attended the game into self-isolation.

In his media conference on Wednesday the Prime Minister appeared more prime ministerial in tone than at any point during his 18-month tenure to date. But the uplift in his communication skills, both compared with his handling of the bushfires and his inconsistent messaging to date during this crisis, doesn’t necessarily mean that the right decisions are being made.

Why is it so important we continue to scrutinise if our political leaders are making the right decisions, rather than blindly accepting what they tell us?

Do the maths.

Peter van Onselen is political editor for Network 10 and professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

“Do the maths.” Whether intentionally or otherwise, in just three words, Deputy Chief Medical Officer Paul Kelly highlighted the gravity of the coronavirus in a way no politician has been willing to.