Coronavirus: Economy lurches into unknown territory

The waste and unintended consequences from the virus response will make Rudd’s GFC stimulus look like teething problems.

The impact of COVID-19, and more particularly the responses to it, dwarf the impact of all the recessions since the Depression of the 1930s, which took its toll gradually. During World War II, economic activity rose 26 per cent in the six years to 1946 and the jobless rate fell to 1 per cent.

In six weeks almost one million Australians have lost their jobs and the economy has shrunk about 10 per cent — the fastest rate ever. Big dollops of foreign exchange earnings — mainly from tourism and education — have evaporated, and immigration, the underpinning of economic growth for almost a generation, is set to slow to a trickle, potentially for years.

The coronavirus crisis will divide history just as September 11, 2001 did.

“Bar the traumatic declines in economic activity in one or two economies following the fall of the Soviet Union, nothing like this has been seen since World War II, indeed since the Great Depression and, before that, the chaos of post-World War I restructuring,” says John Llewellyn, former chief economist at Lehman Brothers through the global financial crisis.

Around $4bn of national income — the annual budget of more than three ABCs — is being forgone every week, Josh Frydenberg said this week.

Reflecting the divide among economists over whether the economy is facing a V, L, U, W or backwards J recovery, the Reserve Bank’s quarterly economic update singles out “the extremely high degree of uncertainty about the economic outlook”.

Its worse-case scenario has the jobless rate still a little under 8 per cent in the middle of 2022, and output about 3 per cent short of its level at the end of last year. The best-case scenario sees a sharp fall in the unemployment rate from the 10 per cent peak expected in June, to about 5 per cent within two years.

“The outlook for the domestic economy depends on how long social distancing remains in place,” the RBA says.

“It’s quite possible the current disruption will have some long-lasting effects, not only because it will take some time to restore workforces and re-establish businesses but also because it could affect the mindsets and behaviours.”

The economic shock will likely lead to large increases in saving rates and deferred purchases of non-essential goods. Car sales plunged last month, to be close to their lowest level in 20 years. The confidence of households and businesses has plummeted.

The uncertainty about the outlook provides some hope.

“Any snap back is likely to be half as big as the initial snap, with the remainder returning over a much longer period,” IFM Investors chief economist Alex Joiner says. “But we need to be honest as economists and admit we’ve not seen anything like this before, where the initial drop is straight down.”

The extent of the “snapback” is the great unknown. How many businesses in hospitality and retail can withstand six weeks of no — and potentially months of anaemic — revenue? And even if pubs, restaurants and cafes are allowed to reopen soon with restricted customer numbers, how many are viable with half or two-thirds the revenue?

“Growth in the population aged 15 years and over is assumed to slow considerably over the next year owing to the closure of borders, before picking up to be 1.5 per cent over the year to mid-2022,” the Reserve Bank says in its statement. Until then, construction will slump along with rents — commercial and residential — and very likely house prices.

That said, the outlook is better than it was a few weeks ago.

“The RBA is probably edging back towards a slightly less negative view, although that’s from a horrific baseline,” says Tim Toohey, chief economist at Yarra Capital Management. “And everyone jumped on the one million job loss figure this week, but the pace of decline slowed and retail jobs didn’t drop off as much as feared.”

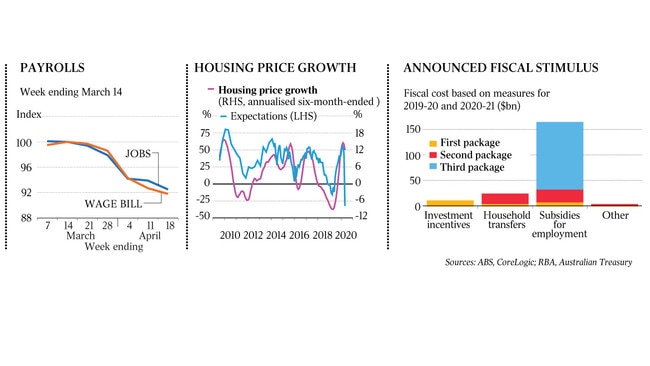

On Tuesday the Australian Bureau of Statistics revealed 7.5 per cent of jobs had vanished since mid-March, sapping the flow of wages and salaries by 8.2 per cent.

Toohey sees a jobless rate of 12 per cent by June still. And the wages slump “is 7.7 times the next-largest quarterly decline, recorded at the height of the 1983 recession”, he notes.

The supercharged Newstart payment, doubled for six months from March to about $1100 a fortnight, could perversely draw a lot of these people into the labour market.

“A lot of people forget we have 1.4 million people who say they want a job but aren’t counted as unemployed,” Toohey says. They may not bother jumping through the eligibility hoops for $500 but they will for $1000.

To be counted as unemployed — and qualify for benefits — one must have applied for a job in the week of the ABS survey and be available to start work within a fortnight.

Longer-term, though, a slump in immigration could see a lower jobless rate and upward pressure on workers’ wages.

“Recall if we had a (lower) US workforce participation rate, and (lower) US population growth rate, we would have 1.5 per cent unemployment rate,” Joiner says.

“Even though the Australian economy has generated twice as much jobs growth as the US recently we still, because of the growing labour supply, couldn’t get the unemployment rate down.”

The export sector has worked in our favour too. The trade surplus in March was almost double expectations, at $10.6bn, as shipments of iron ore — whose price has increased 5 per cent in the past few months — surged.

“Chinese demand for imported iron ore has remained fairly strong, reflecting some disruptions to domestic production, the gradual resumption of domestic economic activity and rebuilding of inventories in anticipation of government stimulus, which could boost demand for steel, “ the RBA said on Friday.

The export surge combined with the toilet paper stampede in March — encapsulated by the unprecedented surge in retail sales of more than 8 per cent for the month — could even see GDP in the first quarter of the year slightly positive. That would mean a technical recession would be avoided, based on the standard definition of two successive contractions. The federal government alone has launched stimulus budgeted at $214bn across the next few years, which is expected to almost double net debt as a share of GDP.

Right now the emphasis is understandably on health outcomes. As the virus recedes, the focus will shift to the economy. “You’re almost out of recession before bankruptcies have reached their peak,” says Toohey.

The waste and unintended consequences stemming from the series of huge stimulus packages will make the Rudd government’s GFC stimulus look like teething problems.

Governments desire to win the next election at least as much as they want to make the best decision for the long run. On Toohey’s calculations, the stimulus offsets the hit to labour income for the rest of the year. “July will mark the peak stimulus month, with labour income better off by an estimated $15bn in that month,” he says.

The government should bring forward its scheduled tax cuts, slated for 2024, too. “They could say, ‘Well, look at what we’ve just done for the bottom two-thirds of the income distribution’,” Toohey says.

“It’s a little unfortunate people in the most vulnerable hospitality sectors, some casuals, don’t meet the criteria while we’ve been a bit freewheeling with some higher-income earners,” he adds. Nevertheless, he gives the packages high marks.

About 6 per cent of the 720,000 businesses that have applied for JobKeeper are high-income partnerships and sole traders. Even if incomes bounce back by July, the $1500 a fortnight will extend to September. It’s a questionable use of public funds, but ultimately small fry given the government has fired a bazooka.

Even the Labor Party has conceded it will have to re-evaluate its spending promises, tacitly admitting there will be less money for education and health.

Whether the economic impact is worse than World War I, which maimed the nation in every respect more than World War II, remains to be seen. GDP in 1919 was still 4 per cent lower than in 1914, according to Ian McLean’s book, Why Australia Prospered.

If I had to bet, I would say not. A V- or U-shaped recovery rather than a depressing L or W seems more likely: the fiscal stimulus is colossal and the threat of the virus appears to be receding. Loss of control of, or confidence in, the monetary system as a result of rampant money creation appears a likelier outcome than an entrenched, 1930s-style depression.

In 2003, Nobel laureate Robert Lucas declared famously that “the central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades”.

In any case, it’s a salutary reminder experts can get it very wrong.

Even if 850,000 Australians are back in work by July, as Scott Morrison signalled on Friday when he laid out the three-stage plan to reopen the economy, the social, economic and political effects will be long-lasting. Not in a century have we as a nation become so poor so quickly.