Coronavirus: Complacency lulled all of us into delusion

The world forgot the lessons of the past that may have helped us prepare for the coronavirus crisis.

The coronavirus crisis has arisen so quickly and is now so global that most Australians, far more than our governments, are knocked off balance. We are bewildered partly because it was so unexpected. We have lost our knowledge of medical history, and so we were not prepared.

We are also puzzled to see China, and its authoritarian rule, eventually coping more effectively than Western Europe with the virus. The bold shutdown of northern Italy inspired hope; the subsequent surge in deaths in Italy foments fear.

We are also bewildered by the sudden arrival of a kind of infectious fever in economic life. Until three weeks ago, it was widely believed that this pandemic would not heavily damage the world’s economy. We failed to notice, however, that a global economic system so reliant now on tourism and other tertiary industries was especially brittle. Australia’s economy, stronger than most, is likely to be severely wounded this year, even after Canberra’s bold bout of bandaging.

Not long ago we were assured that climate change was the unprecedented disaster threatening the world, and now another crisis has pushed it aside. An earth-shattering warning, issued year after year, cannot instantly be replaced by another warning that is even more urgent. Few governments in history have been told, almost overnight, to march to a different drumbeat.

This difference between the mental moods and the priorities of two successive years is almost unique. It has magnified the work of national leaders, scientists, the medical and nursing professions, big business and small, the media and all who teach.

Food and Rationing

Few events in recent weeks have been so astonishing as the occasional stampede in supermarkets; the tussles over toilet paper, the rush for fresh meat, and the hectic pursuit of tinned beans and tomatoes, bags of flour and rice, and biscuits — for cats and dogs. There cannot be a real fear of food shortage, because in nearly every year Australia grows far more food than it can eat. I estimate that today every populous country in Europe and Africa is more in danger than Australia of running out of food.

At the same time, only a few shoppers are using their elbows or showing panic. The television news does not catch the cheerful and orderly scenes in supermarkets in Adelaide or in the Queen Victoria Market last Saturday morning in Melbourne. Moreover, government officials with the best intentions had initiated the panic by recommending that a typical Australian household should stock up to 14 days of food, “just in case”. Even the US Department of Homeland Security is recommending two weeks’ worth of supplies in each home. As for those people who were forced to quarantine themselves for 14 days, they had no alternative but to visit the supermarket and buy as much food as they could carry, and hoard it.

Yes, at first much of the hoarding was officially fostered or encouraged. This might be the first time in Australian history that leading officials have recommended the hoarding of food across the nation. Certainly, hoarding had not been encouraged in another acute national crisis, the darkest years of World War II. The official advice in 1942, when the Japanese threat was at its height, was the exact opposite: Do not hoard food. Instead, the federal government in effect arranged the hoarding and distributing of food on behalf of all the people.

Such vital items as butter, meat and tea were rationed — clothes and petrol too. Ration books or booklets were distributed to all citizens. With the aid of scissors, the butcher and grocer snipped the correct number of ration coupons from each booklet. Some foodstuffs were not rationed: they were simply unprocurable.

Looking back, we should notice an episode that will become important in the global analysis of why various politicians and scientists in the Western world were taken by surprise this year. The SARS outbreak that peaked in 2003 possibly misled them. Those who were sick, especially in China, were obviously in peril. The fear that the virus would spread was intense. Tens of thousands of Australians who planned a holiday in Europe postponed or cancelled it. Our family was among those wondering whether to stay at home. Worldwide, 8098 people contracted SARS but in the final count only 774 died. The death toll of the new coronavirus, at more than 10,000, is already almost 13 times that tally.

The conquest of SARS probably made us too confident. Medical science had triumphed yet again. At the onset of each winter, the increasing practice of administering flu injections, especially to the old, inspired a vague air of confidence.

You may argue that what we think as individuals is not that important. Living in a democracy, we know that public opinion can be crucial. Medical scientists can give their learned opinions, politicians can act on them, but if they fail to persuade the people, plans soon flounder or miss their targets.

A little more than a decade after the height of the SARS pandemic there arrived a warning that we did not seem to hear. The Ebola epidemic of 2014, starting with cases in the small West African nation of Guinea, was devastating. It frightened nearly all who tended the feverish sick. More than 11,000 people died; nearly all were Africans. Africa is a blind spot for most Westerners. Captivated by the River Nile and the Zambesi Falls, they bypass the tent hospitals where the Ebola victims died.

If that virus had claimed most of its victims in France, Italy or even Hong Kong, we would have learned much about it, and been shocked by its capacity to stop its victims from breathing. Ebola should have been another warning that new viruses were continuing to arise and erupt, and that their death rates might be disturbingly high. It should have prepared us mentally for Wuhan.

In retrospect, the warning that should have been etched in our mind was the influenza disaster of 1918-19. It shook and shocked Australia. According to professor John Mathews, an Australian expert on pandemics, this worldwide event “proved to have some gene segments like those from pig and bird influenza, which explains why it was new to humans in 1918”. Wartime conditions helped this so-called Spanish flu to spread in crowded army camps.

Actually, the influenza reached Europe in the troop ships from North America in the final months of World War I. In short, these packed ships were incubators or hothouses of infectious disease. It was a foretaste of tragic events in the cruise ship moored at Yokohama early this year.

Western Australia’s first clear sign of the disease came in a troopship from Britain in December 1918. The Boonah approached Fremantle and sent ashore the news that 337 soldiers were ill; the tally was soon stretched out by another 44. After the ill soldiers were sent ashore to a quarantine station, the ship was thoroughly cleaned before departing for Adelaide, where another 14 cases of the virus were detected. Meanwhile, in sight of Fremantle, a few of the pale-faced soldiers and the women who nursed them died from the virus.

When another troopship faced quarantine near Fremantle, a group of homesick Australian soldiers decided to escape. Lowering four lifeboats they were approaching the coast when captured.

On the Western Front and in the army camps, the influenza had spread first among the Allies and then the Germans, Austrians and Swiss. It migrated in several short-lived surges but Australia and the South American republics at first seemed immune. Perhaps, it was said hopefully, Australia was quarantined by distance.

The fever struck hard in 1919, and perhaps 15,000 Australians died. As the collecting of statistics varied from state to state the death rolls were imperfect but most victims were aged 25-40. Sometimes father and mother died but not the children. If the same proportion of the Australian population were to die from the coronavirus as from the Spanish flu, that would mean 70,000 deaths. It is a sobering thought.

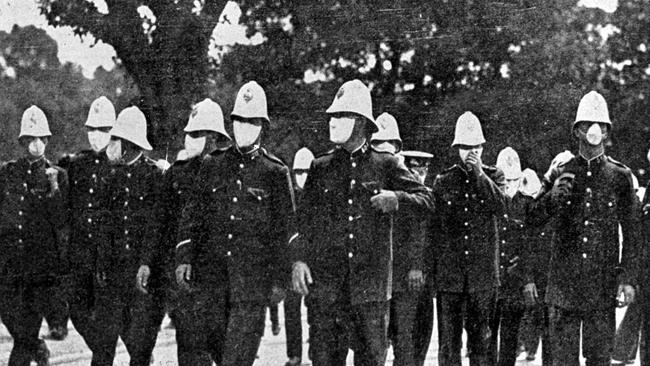

Everyone wears a mask

How did Australians cope with that virus? The state governments, more powerful than they are today, had many disputes with the federal government. The states imposed their own laws on interstate movements of people. Western Australia sabotaged the new transcontinental railway for three months. At Albury and other border towns, travellers from interstate were halted or turned back. Trade unions fought with governments on how to handle ships and infected passengers.

NSW, the heart of the epidemic, was the most drastic in its laws. On February 3, 1919, premier William Holman announced that “a danger greater than war” faced his people and “threatens the lives of all”. In capital letters he commanded: EVERYONE SHALL WEAR A MASK. Holman prohibited church services in Sydney and suburbs, banned race meetings, and closed theatres, music halls, libraries and those popular meeting places, public billiard rooms.

Though most of his bans did not last long, they mirrored the panic in the air and a sense of foreboding that appears to have been deeper and more pervasive than any we have experienced in Australia this year. They had every reason to be frightened. Their doctors did not know the cause of the new pandemic: moreover, antibiotics had not yet been invented.

Australians already knew how devastating the virus had been in Europe. There it had killed more people, both civilians and soldiers, than all the guns of war. The English newspapers that reached Sydney by sea told of individual tragedies. Brave soldiers who had escaped death in battle a dozen times were now, the war over at last, part of “the harvest chosen for the scythe of the Angel of Death”.

Last year was the centenary of that influenza pandemic. As a nation we failed to remember it, largely because it coincided with the signing of the peace treaty that ended World War I and created a new Europe.

I was one of the historians who, last November, should have given the Spanish flu more attention when I spoke at dinners celebrating the Treaty of Versailles and the end of the war.

It was vital that the tragedies of 1919 should be inside our national memory. They convey the message: Be prepared. But this year we were not prepared, mentally, for a new pandemic.

Messages culled from China and Italy?

We have been stunned by the speed with which a medical crisis in a Chinese riverside city spread across the world. The explosive nature of the coronavirus was largely to blame but world officials can also be blamed a little. The heads of the World Health Organisation, reading aloud their slow lectures, failed to call it a global crisis, a pandemic, until some weeks after it was self-evident. They intimated that they were frightened of promoting panic. Well, they did just that.

The crisis has altered our way of life in no time. Four weeks ago, who would have predicted that the whole timetable of sport here would be overturned? In no other nation has spectator sport been so influential for so long. Even in World War II, the football league in Victoria, with the specific blessing of prime minister John Curtin, had continued season after season, drawing large crowds even when the Melbourne Cricket Ground was occupied by the beds and offices of the armed forces.

But now the coronavirus is silencing what even the war did not: the infectious roar of the crowd. Some hardened supporters would prefer to keep the crowds and ban the players, including those of the opposing team.

But then this is a kind of war. In effect, war is being declared by our combined governments, Liberal and Labor, and their daily bulletins of instruction. There seems to be no alternative but to act swiftly.

This week the nation’s leaders reached another eye-opening decision. Meetings, banquets, lectures and other gatherings in a building cannot be attended by more than 100 people, unless the meetings are deemed essential. Outdoor gatherings have their restrictions too. This is a radical step or trial, and new to our nation. Even in the convict era, no such laws were generally imposed — to the best of my knowledge — on church services, government banquets and naval celebrations.

Schools will be closed from time to time. That debate will run on. But the closing of government schools is not an unusual event. In the 19th century they were often closed for economic reasons: a township ceased to have enough students, or the local farmers need the help of all their children in order to bring in the harvest. During epidemics, some state governments closed schools. When Victoria suffered severely from poliomyelitis in 1937-38, and more than 2000 children and adults were victims, schools were closed. It was a sad blow to education, declared some head teachers, but at the Newtown State School in Geelong one of the many boys and girls who cheered inwardly when the closure of the school was announced was Geoffrey Blainey.

Just as revolutionary is the experimental plan that a large section of the population, especially the old, should impose isolation — or “social distancing” — on themselves, not leaving their home except under certain conditions. Even when they do leave for an hour or two their familiar haunts — cafes, coffee shops, hotels, public libraries, sporting clubs, church groups — will probably not be open to welcome them.

Likewise, the citizens in retirement villages and outback eventide homes will have to accept a high measure of isolation from outsiders, even their own relatives.

To my mind these are justifiable experiments. I cannot think of any precedent in our history, unless briefly in the convict era. But a free nation has to agree to sacrifice temporarily a freedom or two for the sake of a greater freedom, the hope of life.

Geoffrey Blainey’s latest work is The Story of Australia’s People, in two volumes. A revised version of his 2008 book Sea of Dangers has been released by Penguin Random House entitled Captain Cook’s Epic Voyage. Out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout