Coronavirus: China’s ticking time bomb could be about to explode

It’s easy to see why so many pandemic pathogens have sprung out of the region. Experts warn this particular virus is still in its infancy.

Passenger A flies into Melbourne from Wuhan on January 22 before the Chinese government seals off the drab industrial city of 11 million people in a futile bid to halt the spread of the coronavirus. He doesn’t know it — because what he feels is excitement to be on holiday in faraway Australia — but he has brought the disease with him.

The man, 44, boards Tigerair flight TT566 to the Gold Coast five days later. By now, he is probably feverish. Unwittingly, he may have already infected four other Chinese nationals in the tour group. The counter ticks over. Everyone within 1m of him in the aircraft cabin has been exposed.

That means people seated within two rows of Passenger A must be tracked down and screened for coronavirus; so too hotel staff who serviced his room or encountered him at the reservation desk or restaurant. They will be interviewed, possibly tested, and details of their movements and interactions logged in case they become ill. Their children might be kept home from school as a precaution. Or not.

Tick, tick, tick.

And this is only one of the 8100 cases confirmed to date worldwide, nine of them in this country after a 42-year-old woman in Passenger A’s party tested positive.

An interconnected planet has broken down irretrievably the degrees of separation that used to provide early protection against pandemics, which is part of the reason this outbreak is creating such alarm. Nearly 2000 new cases have emerged during the past 24 hours, the vast majority of them in China.

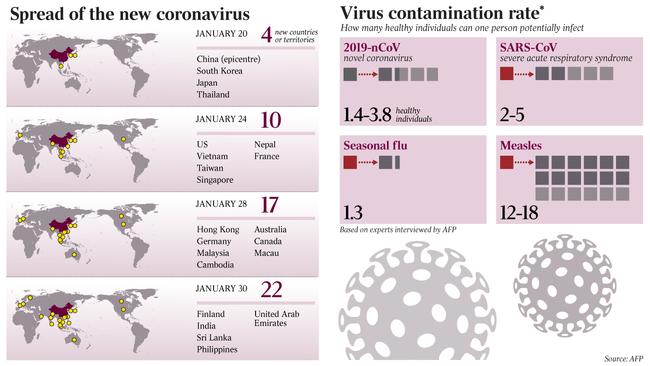

Epidemiologists use a measure called the basic reproduction number — R0, pronounced R-nought — to predict how a contagion such as coronavirus will burn its way through the citizenry. Broadly, this is the average number of people who will catch the disease from a single infected person, in a population that has not encountered it before. If the R0 is greater than one, the infection will probably keep spreading; less than one and it is likely to flame out.

The most consistent estimates for coronavirus from World Health Organisation research teams range between an R0 of two and three. But one Chinese group has put it as high as 5.5.

This in itself may not be as bad as it sounds. The multiplier for the new strain, now called 2019CoV, is in line with a number of other diseases, notably SARS (2-5), the coronavirus that burst out of southern China in November 2003 to cause 8098 known cases of infection, resulting in 774 deaths across 17 countries (none here). Measles, for example, has an R0 of 12-16.

And in the scheme of things, common influenza causes many times that number of deaths with barely a sweat raised by the media — on average 3500 people in Australia annually.

No need to panic

After revealing details of Passenger A’s movements on Thursday, Queensland Chief Health Officer Jeannette Young urged people to keep the risk of coronavirus in perspective. “This is a serious health issue but we are well prepared,” she said. “This is our first case and I strongly suspect it will not be our last case.

“We’ve responded to health emergencies in the past — swine flu, bird flu, SARS, MERS and Ebola — and we’ve done it effectively. Just like you would in flu season, wash your hands regularly, cover your cough or sneeze, and if you feel unwell avoid contact with others and get medical attention.”

Have governments around the world overreacted? There is no shortage of criticism of Beijing’s decision to lock down Wuhan and surrounding centres in thickly populated Hubei province, encircling nearly 60m people. For all its reach, China’s heavy-handed communist leadership has not been able to suppress public anger at the restrictions on Lunar New Year travel, when hundreds of millions crisscross the country or head overseas, and the disruption that is now hitting offices and factories, shuttering places where people gather or socialise as well as schools and universities. Some experts have suggested that the quarantine measures, too late to matter, will only make matters worse in the hot zones.

This is not the view of the CSIRO’s Trevor Drew, director of the Australian Animal Health Laboratory outside Geelong, the ultra-secure research centre housing some of Australia’s top bio-scientists and the planet’s deadliest viral pathogens. In sharp contrast to its handling of severe acute respiratory syndrome, covered up and downplayed in China until the evidence could no longer be denied, Beijing’s response this time has been exemplary, Drew maintains.

Technological gains

The genome of the novel coronavirus was sequenced within five weeks — against five months for SARS, reflecting the advance in technology — and promptly shared, allowing a research team at Melbourne’s Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity to become the first in the world to grow the virus, a critical step towards a vaccine.

“The response of the Chinese has been extremely vigorous, even though some of the feedback … has been that it might be a bit over the top,” Drew says.

“In fact, I think they are being prudent. At the same time, there may be a recognition that this could ultimately be worse than SARS and they don’t want to be caught on the back foot.”

While the mortality rate of coronavirus is about 2 per cent, compared with up to 7 per cent overall for SARS, rising to 50 per cent for those aged over 50 who contracted it, the veteran virologist cautions that the 2019 strain behaves differently to SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome, also known as camel flu, which kills a third of patients but was confined largely to the Arabian Peninsula after it emerged in 2012.

Researchers in Hong Kong announced this week that bats are likely to have carried the new coronavirus to a so-called wet market in Wuhan, where animals caught in the wild are sold to be eaten alongside the meat, seafood and produce. Genetically, it is about a 60 per cent match with SARS and also closely resembles MERS, both traced to the bat. The transmission path to humans, whether direct from the primary carrier or through an intermediary animal host, such as the skunk-like masked palm civet in the case of SARS, or horses in Australian Hendra virus, remains unknown.

But unlike SARS and MERS, people who contract 2019CoV seem capable of infecting others before showing signs of the illness. With an incubation period of up to 14 days, this sinister aspect of the disease compounds the challenge for health authorities to keep a lid on the outbreak, as demonstrated by Passenger A.

Australians exposed

The rise of China as a determinant of Australia’s national fortunes has rarely been in sharper focus. Inbound tourism tipped $43.9bn into the economy in 2018, nearly a quarter of it spent by holidaying Chinese. But this, in turn, has deepened Australia’s exposure to coronavirus. In 2003, at the height of the SARS emergency, short-term arrivals from China reached 172,300 for the year, according to Tourism Australia; to November last year, that number had increased eight-fold to 1,442,200.

The emergent disease, part of a family of coronaviruses that generally cause disease in humans ranging from a mild cold-like illness to fatal pneumonia, could become more virulent as it moves through the population.

Drew warns 2019CoV could evolve — and he stresses could — to become more lethal. “What I am thinking might be happening here is not that people have been infected for some time with this virus but that it is finding a new niche more slowly, and therefore could ultimately cause more of a problem than we have seen with other diseases because it is not so spectacular early on in its evolution,” he explains. “This … is a particular feature of coronaviruses because of the way they replicate.”

Drew says it might be better to think of the new strain as a cloud of similar viruses, evolving to become ever more dangerous: the key is the environment and the density of potential hosts. Teeming southern China fits the bill. Combine a human population counted in the hundreds of millions with the presence of sizeable, native bat numbers and a crossover agent of wildlife that’s killed on the spot in a wet market or taken home to be dealt with there, and it’s easy to see why so many pandemic pathogens have sprung out of the region. Citing what virologists call quasispecies theory, or mutation-selection balance, Drew says: “I am not saying this new coronavirus is doing this … but they do have a potential for quite rapid evolution. They will not exist as a single virus but as a cloud of similar viruses, and depending on the environment they find themselves in, particular attributes will be selected in or out because they benefit that particular group.

“So in a very high host-density environment you may well find that more virulent viruses emerge from that cloud and, conversely, in a very sparse host environment it may well become less virulent and even die out.”

Friday’s declaration of a global health emergency is formal acknowledgment by the WHO that the crisis is indeed grave, with 22 countries, including China, now registering confirmed infections cases, and the number of cases on track to surpass the combined tally for SARS and MERS.

On the positive side, the speed and scope of the Chinese response, lauded as “monumental” by WHO boss Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has underpinned an international research effort to fast-track the development of a vaccine. Batches of the homegrown virus from Mike Catton’s team at the Doherty Institute arrived at the AAHL on Friday, one of only five top-tier PC4 labs in the world capable of handling such a dangerous pathogen.

CSIRO director of health and biosecurity Rob Grenfell says pre-clinical trials of a vaccine could start within four weeks, an astonishing turnaround. At the same time, a team of molecular biologists and mathematicians at the University of Queensland under Keith Chappell is finetuning a revolutionary “plug and play” vaccine, a kind of template that will be able to accommodate different viral threats as they emerge.

“The technology has been designed as a platform approach to generate vaccines against a range of human and animal viruses and has shown promising results in the lab, targeting viruses such as influenza, Ebola, Nipah and MERS coronavirus,” Chappell says.

On a war footing

Together, these projects have put Australian scientists on a war footing at the forefront of the global response that has gathered pace and traction in record time.

Behind the scenes, former federal health department mandarin Jane Halton’s work as chairwoman of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, better known by the acronym CEPI and backed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust, has been instrumental in co-ordinating and funding the work.

Chappell’s research at UQ, supported by CEPI, is one of three projects internationally earmarked as most likely to deliver a working vaccine for coronavirus.

None of this has happened by accident. AAHL was central to creating a vaccine for the Hendra virus, nearly 10 years in the making, and is also involved in developing a treatment for Ebola in the wake of the devastating 2014 outbreak in East Africa.

“Australia is very gifted in the sense of having such great scientific talent, but the challenge for us was to organise these in relation to the particular challenge we are confronting,” Grenfell says.

No one has any illusions about the danger posed by coronavirus or the ever-lurking worry that one dark day a pathogen might go into the churning mix of viral mutation and explode in nightmare form, say with the lethality of Ebola and the contagious properties of flu.

For now, we can be thankful that all that can be done to contain the virus is being done.

Tick, tick, tick.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout