Coronavirus: China’s extreme measures to tackle COVID-19

Totalitarian methods seem to have worked, but that doesn’t make them acceptable.

As the rest of the world is struggling to fathom what a post-coronavirus existence may look like, China claims it is on the verge of declaring a momentous victory in the “People’s War on COVID-19”.

But the Chinese government’s authoritarian path to tackling the deadly virus is not open to the rest of the world. It included:

• Mobilising 91 million party members to act as neighbourhood behaviour enforcers.

• Intensifying the “grid management” system that corrals every 200 families under a supervisor with 24-hour-a-day scrutiny powers, including comprehensive CCTV coverage and facial-recognition technology.

• Harnessing the almost universally used apps of top internet corporations Alibaba and Tencent, which runs WeChat, to allow the government to track everyone’s movements.

• And, horrifyingly — if some reports on social media are to be believed — the tying of people to poles, or publicly humiliating them in other ways, for violating prevention measures.

Such harshness contrasts with the virus measures undertaken with considerable success by neighbours of China, including Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea, which along with painstaking attention to detail — including chasing down the contacts of each person afflicted — are building substantially on deep reserves of civic trust to achieve overwhelming consent for their programs.

There is no evidence yet that a third way can have any success.

The official numbers out of China are hotly contested. As of Tuesday, the Chinese government said the country had recorded 81,171 coronavirus cases, resulting in 3277 deaths.

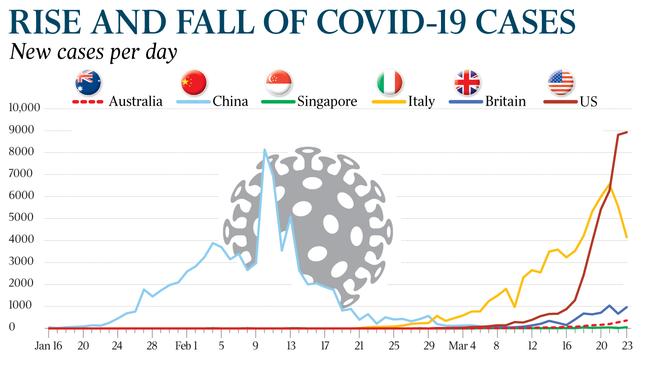

At the peak of the virus in China in the middle of last month, 14,000 new cases and 150 deaths were reported for one day. On Tuesday, there were only 39 new confirmed cases — none in Wuhan — and only nine recorded deaths.

But according to a report in the South China Morning Post on Tuesday, which cited classified government data, China has under-reported its confirmed COVID-19 cases by one-third, or more than 40,000 infections, while leader Xi Jinping has been described by Xinhua news agency as “the People’s Leader commanding the decisive battle”.

The decision to leave asymptomatic patients out of the country’s confirmed tally has not necessarily affected the success of its quarantine efforts, however, because, although not counted, patients without symptoms still were isolated in coronavirus facilities.

Putting aside the quibbling over numbers, China’s “effective” strategy in slowing the transmission of the virus has given rise to a fresh narrative — that the new era of Chinese socialism holds the answers to the world’s apocalyptic challenge.

The surveillance tactics employed by China have held little regard for personal liberties.

Soon after the initial discovery of the virus, everyone in China was assigned a green, yellow or red health status code that ubiquitous officials could check instantly on their smartphones to decide where people were permitted to go.

This is all happening as the Chinese Communist Party regains full and firm control of its social media and banishes more Western journalists, while Western pundits, especially on social media, launch viral onslaughts on their political leaders over their handling of the pandemic and even urge fellow citizens to break laws.

China is selling itself as the resolute leader of humankind’s “shared destiny”, eyes ahead, with the West left dithering in a delusional past.

China’s propaganda outlets are proclaiming its altruism and generosity in spreading its antivirus expertise and its bounty of masks, testing equipment and other health products to smitten countries around the world, although some of it has been targeted especially at ethnic Chinese populations in foreign lands.

The message of Chinese success is being amplified by international elite supporters such as Jim O’Neill, the celebrity former Goldman Sachs economist, who praises the “tough, aggressive” response of China, without referring to instances in places such as Wuhan, where officials welded some of those suffering the virus into their own homes.

This take echoes that of Christiana Figueres, who for six years was head of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and recently visited Australia to receive the 2020 Sydney Peace Prize’s gold medal for human rights. She previously has praised China’s leaders for “doing it right” because the party’s political system “avoids some of the legislative hurdles seen in countries including the US”.

She’s correct, of course. But it’s not just “some” legislative hurdles that the CCP’s leadership does not countenance. It’s all of them — as well as judicial, civil, popular, electoral, or any other infernal type of hurdle. This muscular, brook-no-wimpish-rights-or-accountability-nonsense ethos is now being compared with the claimed weakness of Europe and the US.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian says: “China’s signature strength, efficiency and speed in this fight have been widely acclaimed. To protect the health and safety of people across the world, the Chinese people have made huge sacrifices and major contributions.”

The core of the new narrative of victory by Xi and the CCP against the deadly virus has been firmly entrenched. “Xi is the backbone of this battle,” proclaims Liu Jingbei, a professor at the party academy in Pudong, Shanghai.

Xi finally visited Wuhan a dozen days ago. He stayed about nine hours, speaking to a few scrupulously screened party officials and health workers, and to some patients via video screen. His “walkabout” was confined to an area where officials had been consigned to every residence and snipers to rooftops, following the rare and thus shocking heckling of Deputy Premier Sun Chunlan a week earlier, when angry residents shouted at her: “Fake, fake, it’s all fake!”

Accompanying Xi on his brief foray to Wuhan was the CCP’s next most important leader: Wang Huning, its chief strategist and propagandist, creator of the “Chinese dream”, the Belt & Road Initiative, and “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism With Chinese Characteristics for a New Era”, which is nowpart of China’s constitution. Since their visit, the propaganda efforts around virus victory have intensified markedly.

Those concerned about any residual virus vulnerability of China’s leaders — Xi and Wang and their five colleagues on the politburo standing committee are all men in their 60s — should rest easy. They live, as their predecessors have largely done since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, in handy isolation from the rest of the population.

Politburo members eat food specially grown for them in set-aside and guarded farms, travel totally apart from the public, always stay in guesthouses specially maintained for them when they travel around China and never in hotels, do not eat in restaurants with members of the public, and never go to shops or to museums unless they are closed off from the public.

Visits from even their closest friends and relatives need prior registration with security services. Their homes are located in guarded compounds — chiefly Zhongnanhai, the communist Forbidden City in Beijing.

Of course, all such leaders have privileged access to health services that are entirely separate from those available to the broad community, with history showing that the very top leaders tend to be treated at elite military hospitals.

So, any additional antivirus measures to keep the top cadres out of harm’s way need not be that onerous. And as seen in the special visit to Wuhan, the contact duration of leaders with others is strictly limited, the pre-encounter efforts exhaustive, and each meeting curated down to minutiae.

As the true dimensions of the coronavirus threat began to emerge last month, a different disease began to spread that, if it had gained a hold, might have caused existential trouble for the CCP — namely, questioning and debate. Dr Li Wenliang, the whistleblower hero ordered to repent for “spreading rumours” via WeChat, and who later died from the virus, responded: “A healthy society cannot have just one voice.”

Whereas online posts critical of the party or its leadership have always been taken down, now their writers are usually also taken in for extensive grilling by public security officers, and are required to disavow their views and to sign pledges of loyalty.

It is a tribute to the sheer power that the party can bring to bear within China, to its adroitness at seizing political and propaganda openings, and to its new-found capacity to pull strings around the world, that Han Jian, director of China’s Industrial Economics Association, could declare audaciously and credibly, in the face of a slump in trust among many inside China, that “it is possible to turn the crisis into opportunity — to increase the trust and the dependence of all countries around the world on ‘Made in China’.”

But at what cost?

China’s most famous artist, Ai Weiwei, writing from exile in Berlin, asks in response: “If the PRC’s systemic illness continues to worsen, and to spread by contagion, the world may have to face the existential questions that the illness raises: can civilisation survive without trust? Can government that lacks legitimacy survive indefinitely?” And he quotes his father Ai Qing, then China’s most famous poet, who wrote in 1938 as Wuhan fell to Japanese troops: “If I were a bird / I would sing myself hoarse / About this land torn by storm / This raging river that surges around our anger … / Why are there always tears in my eyes? / I love this land too deeply.”

While the PRC certainly has grappled successfully, if belatedly with the virus, using its authoritarian clout to lock down much of the country, democratic Taiwan has become a model of success using a very different path — in health control as well as governance. Taiwan moved swiftly and decisively before the end of last year, with the important background of lessons learned from the disaster of the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. In place was easily accessed and well-resourced universal healthcare, cutting-edge tech and big data, as well as the “X factor” — widespread trust in government, recently re-elected in a landslide, and equally crucially, mutual trust between citizens.

A Central Epidemic Command Centre was established, led by Health Minister Chen Shih-chung, on January 20, allocating funds, mobilising personnel and issuing three or four fresh instructions daily, which are publicised in hourly bulletins on all television and radio stations.

Travel bans are tough. The contacts of those infected are traced and isolated. The movements of those in mandatory self-isolation can be tracked through location-sharing on their smartphones. Rapid research and manufacture produced efficient testing kits. Soldiers have boosted masks output, with everyone able to buy at least three a week for a few cents each. Temperatures are checked and hand sanitiser dispensed to everyone in public buildings.

Taiwan, with a similar-sized population to Australia, integrated its health, immigration and Customs data so that travel histories could be swiftly reviewed during the weeks when many flights were still arriving.

And it has achieved the exemplary result of only 195 confirmed cases and only two deaths, while remaining cut off from formal advice from the World Health Organisation, which insists Taiwan is a mere province of the PRC.

Taiwan health officials say they warned the WHO about the virus in late December, but its concerns were not passed on.

Rowan Callick, twice a China correspondent for The Australian, is an Industry Fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.