Coronavirus forces Australia to face a recession

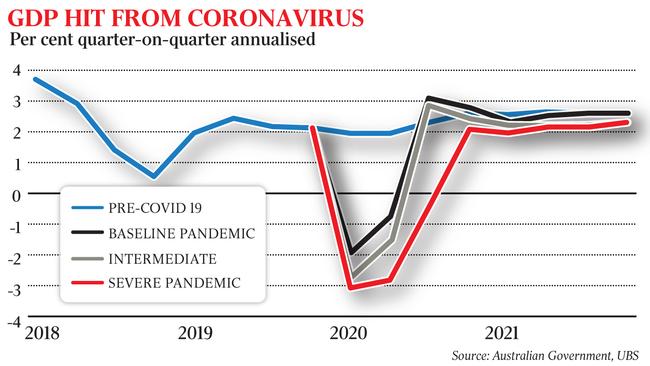

It’s the response to COVID-19 that’s generating an almost certain recession, rather than the virus itself.

“Recessions kill people, too,” says Bob Gregory, who has seen his share of economic downturns, and knows the social havoc they can wreak.

The 80-year-old emeritus professor of economics at the Australian National University — and former Reserve Bank of Australia board member — says while recessions invariably lead to collapses in income and employment, that in turn fuels suicide, alcoholism and social breakdown.

“The big deficits will crimp future investment in hospitals and that kind of public infrastructure that saves lives,” he says.

The octogenarian, currently holed up in his Canberra home — “the university is frightened I’ll die if I come in” — was on the RBA board for a decade to 1995, during the economic turmoil of the 1991 recession that threw an extra 500,000 people onto the dole queue within 12 months.

“This recession — the first one ever triggered by coffee shops, restaurants and airlines — will be very deep and long,” he tells The Australian. “We have to be humble given the enormous uncertainty, but it’s more likely we’re looking at a jobless rate of 8 per cent rather than 6.”

The unemployment figures released on Thursday showed a slight fall, to 5.1 per cent in February, but those numbers now seem almost quaint — reflecting the relatively carefree period before the coronavirus shook business and consumer confidence, and financial markets, with a severity not seen since the global financial crisis.

Qantas’s decision to stand down 20,000 workers until May is the first wave in an emerging unemployment tsunami, as governments move to flick the off-switch across vast chunks of the economy in an effort to stifle the spread of COVID-19.

Unprecedented jobless

A jobless rate of 8 per cent would mean an extra 400,000 people looking for jobs, bringing the total to 1.1 million, a figure unprecedented in Australia.

Any recession won’t be formally declared until September, when the GDP figures for the June quarter emerge. But Australia’s record unbroken economic expansion, a boast beloved of politicians for years, is certainly over.

Internet searches for “recession’’ — arbitrarily defined as two consecutive quarters of economic contraction — have skyrocketed this month. Household confidence, already low, is set to dive as share prices collapse, sapping consumption, which makes up almost 60 per cent of economic activity.

“You go back to every major recession at this equivalent point in time, and everyone knows it’s coming — but they consistently underestimate how bad it’s going to be,” Gregory says.

Almost 60 per cent of businesses surveyed by Roy Morgan last weekend said the economy was already in recession, with the most pessimistic respondents coming from Queensland, where almost three-quarters of business owners were of the view that the economy hit the wall weeks ago. Panic is palpable. Before a dollar of the federal government’s first $18bn stimulus package has been spent, a much larger second one will be announced. And the RBA’s decision to cut the cash rate to 0.25 per cent was an unthinkable scenario a generation ago.

Our biggest trading partner, China, the engine of the global economy, will be lucky to grow 2 per cent this year, down from 6 per cent last year. “An enormous first-quarter shock in China, shutdowns across the US and Europe, and local virus transmission guarantees a deep recession across the Asia-Pacific,” said Shaun Roache, the chief Asia-Pacific economist at S&P Global Ratings.

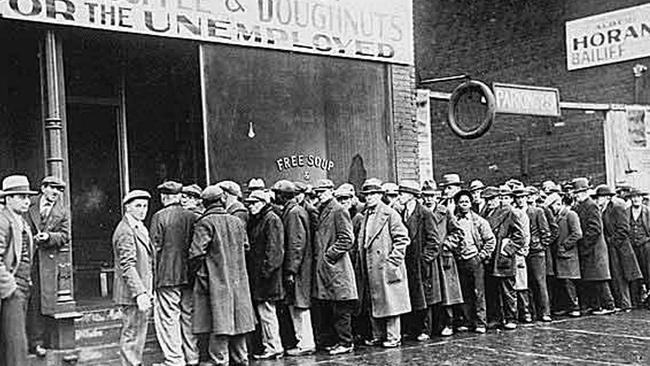

The slump in economic activity could be far larger than any time since the 1930s. “We are facing a joint health and economic crisis of unprecedented proportions in recent history,” says Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley. “The coronavirus is creating a situation where, for a brief amount of time, 50 per cent or more of people may not be able to work,” he tells The Australian.

If GDP falls by 50 per cent for one month, followed by a 25 per cent reduction the next month as some workers return to their jobs, annual output growth would decline by 6.5 per cent relative to the previous year, Gourinchas estimates. “Extend the 25 per cent shutdown for just another month and the decline in annual output growth reaches almost 10 per cent.

“Such a sharp but short-lived decline in activity does not seem unreasonable if one thinks that a majority of the labour force is currently shuttered at home in places like Italy or China.”

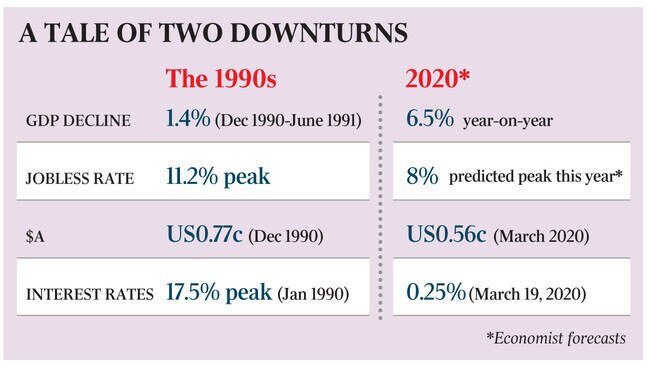

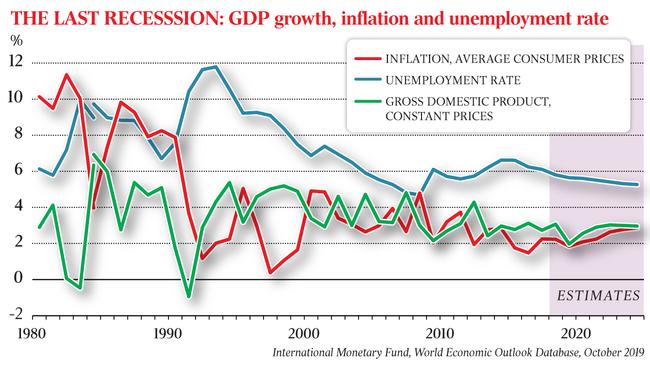

Veteran economist Saul Eslake agrees. “It’s by no means implausible the downturn could be harsher than that of 1991,” Eslake says. Then, the jobless rate jumped from 6.6 per cent in mid-1990 to 9.5 per cent in June 1991, the trough of the recession.

No recession the same

It peaked at 11.1 per cent in 1992 and took seven years — until late 1999 — to get back to 6.5 per cent. From peak to trough the economy contracted by 1.4 per cent.

In the recession of 1982 and 1983, the economy shrank by a cumulative 3.5 percentage points, while the jobless rate surged from 6 per cent to 10.5 per cent.

Leo Tolstoy’s quip about families — happy ones are all alike but every unhappy family is miserable in its own way — might apply to economies too. Recessions manifest for a variety of reasons.

In 1986, then treasurer Paul Keating feared we’d become a “banana republic” unless our trade balance improved. Double-digit inflation was the norm in the 1980s, and the RBA sent interest rates soaring to a punishing 17.5 per cent by early 1990, up seven percentage points from 1988. “The board was acting early to lift interest rates to create a recession, to avoid a deeper one later. It worried inflation would break out,” says Gregory.

It’s not only much lower interest rates that could lessen the blow this time around. The dollar crashed below US60c this week for the first time since 2003, providing a cushion, however uncomfortable, for export sectors not affected by curbs on international travel. Back then, the relatively recently floated dollar was trading around US77c for almost all of 1990 and 1991.

Alan Oster, National Australia Bank’s chief economist, isn’t as pessimistic as others. “It’s not going to be as bad as 1991; unemployment is not going to be 11 per cent,” he tells The Australian. NAB expects the jobless rate to rise to about 6 per cent by year’s end, a modest rise compared with the surge in unemployment that accompanied earlier recessions. “Everything pretty much fell over in the 1990s; this time it will target particular sectors,” Oster says.

The financial system appears in much better shape this time too. “If you go back 50 years and you had a recession, the people knocked out were the breadwinners,’’ Gregory says. “What’s interesting about this time is a lot of job losses will be focused on casual workers, in families where there’s someone else working. Households are more insulated.’’

New world order

In the accommodation and catering sectors, which make up about 7 per cent of the workforce, about 60 per cent of workers are part-time staff.

Also, government and the central banks are acting far more aggressively than they did in the early 1990s, says Eslake.

“Back in the early 1990s, this was the first stage of the period where there was economic orthodoxy against using counter-cyclical fiscal policy,” he says. “A key difference with this recession is that, unlike the last two recessions, this time we know it will come to an end. Indeed, it’s been caused by the measures the government has taken to contain the spread of virus, which is not a criticism.”

But Warren Hogan, an economist at the UTS Business School in Sydney, stresses the longer-term costs of aggressive government intervention.

“In two years’ time our budget could be in as bad a place as monetary policy — that is, very little conventional policy capability. We could have a $100bn budget deficit,” he says.

There are other reasons why this recession could be worse than the one of three decades ago. Certainly, it will be the quietest downturn ever, given swaths of the population will be at home, too worried or not allowed to go outside.

“I must be spending around $100 a week less being stuck at home,” Gregory notes, illustrating how much working from home will kneecap many services.

“Self-isolation means workers won’t be spending as much on lunches, transport, clothes, and make-up.

“I feel that if I go in to uni everyone will look at me like I’m doing the wrong thing. I was also going down to the coffee shop, but I can’t even do that,” he muses.

Higher-income workers in media and the public service can work at home, but the overwhelming bulk can’t. Construction and retail alone employ 1.2 million and 1.3 million workers respectively.

And for those white-collar workers who have suddenly been forced to work from home, productivity won’t be as high, as they grapple with looking after children and potentially inferior information technology.

One of Australia’s leading global fund managers, Magellan Financial chief executive Hamish Douglass, wouldn’t rule out an economic depression in remarks on Thursday, warning of a “near total shutdown” of the world’s economy and a “near total collapse in demand”.

The economy shrank by about 10 per cent in the depressions of the 1890s and 1930s. For Australia, the Great Depression wasn’t as bad as the first, but unemployment still increased rapidly to 19.3 per cent soon after the 1929 stockmarket crash, before reaching a peak of 29 per cent in 1932.

“We could be seeing a fundamental shake-up of the global system — what pops out at the end will define a new world economic and political order for decades to come,” says Hogan.

Many won’t survive

“The concern is that we’ve accumulated zombie firms across the world economy and the magnitude of the demand shocks means many will not survive, mainly because we can’t reduce their funding costs any more,” he says.

Some businesses will be able to alter their operations. Roy Morgan Research, for instance, which employs about 1000 staff, conducts interviews with almost 100,000 Australians face to face in their homes every year. That can’t happen for now.

“Within three days we were working remotely; interviewing is now being conducted via telephone, online and mobile,” says the company’s chief executive, Michele Levine.

But many other businesses don’t have the luxury of such flexibility. Barely four people had lunch at popular Italian restaurant Beppi’s in East Sydney on Tuesday. “Last night we had 50 bookings and 30 cancelled,” the night’s underemployed waiter said.

The sparsely populated restaurant illustrates Gregory’s theory, that it’s the response to coronavirus that is generating the recession, rather than the virus itself.

The best we can hope for is that Australia’s containment measures work as well as they appear to have done in China, where infections, let alone deaths, remain a microscopic proportion of the nation’s population.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout