Coronavirus Australia: Abandon the old? ‘Not on my watch’

Thankfully, the new ethos of sacrifice the elderly first has so far not influenced government policy in Australia.

“As a white candle in a holy place,

“So is the beauty of an aged face.”

— Joseph Campbell

“Discard me not in my old age; as my strength fails, do not abandon me.”

— Psalm 71

-

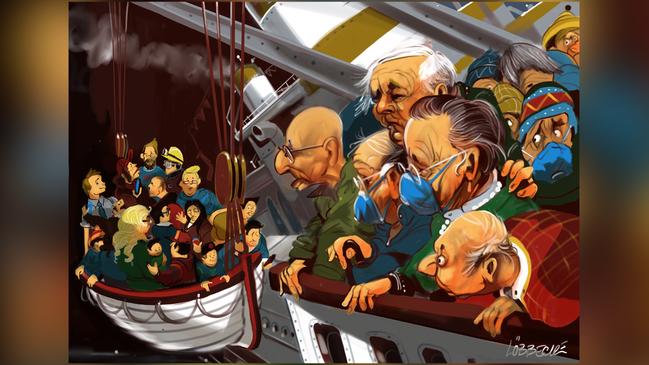

In all the film versions of the sinking of the Titanic, and the attendant tragic loss of life, the rush to the lifeboats is a key moment. The cry is always the same: women and children first.

When it becomes clear there are not enough lifeboats for everyone, only the old and the frail among the men are invited to join the women and children. Able-bodied men are expected to stay behind and take their chances, to do what they can, but essentially to go down with the ship.

This set of actions embodies a principle several thousand years old in Western civilisation (though of course often honoured in the breach) — that the strong protect the weak.

But to listen to much of the discussion around the coronavirus response there is a new idea abroad. How dare we spend so much money, and subject the economy to so much difficulty, to save lives predominantly of people aged over 60? Although this sentiment has not informed government policy, certainly in Australia, it has featured heavily, and in some strangely unlikely sources, in the virus debate. While the virus can kill anybody, it will kill people at higher rates the older they are. Why are we spending so much money to save old folks when young folks will inherit the economic difficulties?

So, if we were to remake the Titanic in the spirit of much of the debate, we would have to rewrite the lifeboats scene. The cry would go out: the frail, the sick, the old, the lame, anyone with a pre-existing medical condition, you stay on the ship, we able-bodied young men are going into the lifeboats because we have the highest chance of survival.

The new ethos of sacrifice the elderly first has so far not influenced government policy in Australia. But it has come into play in countries that have let the virus overwhelm their health system; in Italy, famously, and briefly in parts of the US.

The Italian College of Anesthesia, Analgesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care reported: “It may become necessary to establish an age limit for access to intensive care.” The same body in another report commented that priority should be given, among other criteria, to patients “who have more potential years of life”.

In an early meeting, Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy was briefing Scott Morrison, Health Minister Greg Hunt and a few others on these issues, noting that some jurisdictions were operating a triage system that essentially ruled old people out of intensive care.

“That’s not happening here,”the Prime Minister said. “Not on my watch.”

“Not on my watch either!” Hunt emphatically agreed.

“I’m glad you said that,” Murphy replied, “because I didn’t want it to happen on my watch either.”

That meeting galvanised the determination to secure 7000 ventilators for when the virus might peak, to get enough intensive care beds.

Both Morrison and Hunt told me shortly afterwards that they were determined to fight for every life in Australia. When accused of overreacting to the virus, Morrison told a press conference: “Every Australian matters. It doesn’t matter whether they have just been born or are approaching the end of their lives — every Australian matters.”

And now we seem to be on the brink of victory in round one of what may turn out to be a bout of many rounds with our stealthy, vicious enemy, the coronavirus. Because we flattened the curve so successfully, and not only delayed but perhaps prevented a surge of hospitalisations, our medical resources were never overwhelmed and we never had to confront the worst choices.

If you get sick in Australia, you will be properly treated unless you are very unlucky. Despite all the airy commentary and dogmatic assertions to the contrary, there never was any credible let ’er rip strategy that would not have produced disaster. There was a period early on when Australia had more coronavirus cases in absolute numbers than the US.

But today, a state such as Massachusetts, which has about the same population as Victoria, has had more than 3500 COVID-19 deaths. And they haven’t all been old people. But this should also be borne in mind: many parts of the US have tougher lockdowns than Australia and still they have these horrible death rates. That could easily have been us.

If you let the virus rip, in the hope it would kill only elderly people who you are prepared to sacrifice for the greater good, you would certainly also get a lot of deaths among health workers. Is it fair enough to sacrifice them too for the sake of the economy? What would the utilitarian response be to that? Don’t give old folks who get very sick with the virus proper medical attention, because you’re expecting they are going to die anyway?

This utilitarian approach to life goes in ugly directions. In fact all through this crisis, Morrison has tried to keep as much of the society and economy running as is consistent with suppressing the virus. It is the premiers, also undeniably working towards what they believe is the best policy, who pushed for greater shutdowns.

The obvious point of conflict is schools. All the evidence is that schools are about the safest institution you could open as the virus hardly ever attacks kids. When we reopen more of the economy we probably will get some community transmission. If we don’t open schools until we open other institutions, we will wrongly blame schools for these virus transmissions.

We could easily go into a fantastically damaging cycle of open, then shut, then open, then shut. It is quite possible this virus will come in devastating waves, like the Spanish flu 100 years ago. It is also possible it could be like a guerrilla insurgency, staging sudden, devastating, sneak attacks in areas we thought we’d pacified.

The thing about pandemics is they can get away from you very fast. If the effective infection rate for each patient is one, then after 10 rounds of infection, you have 10 patients. If each infected person infects two others, then after 10 rounds of infection you have 1024 infected people. If the effective rate of infection rises only to three, then after 10 rounds you have more than 59,000 infected people.

We have the disease level so low, and have such a good health and monitoring system, it’s very unlikely we’ll ever get to a New York or Italian-style situation. But it’s by no means impossible. If we stop social isolation practices altogether we could well get there. And if we did, once again the question of how we treat our elderly, what we think their lives are worth, would come back into central focus.

Already we know we have a big problem in nursing homes. The virus hunts out any weakness in a national health system, and that’s where our weakness is.

The arguments about not paying too much attention or devoting too many resources to the elderly come in two forms. One, at the macro level, is: don’t do too much because it’s only old people who will die. And the other is: if there’s any competition about resources, always put the old person last.

Variations of these views, though seldom put so crudely, are, I am sorry to say, popular in parts of the centre-right of politics, especially in the US.

Yet if these attitudes were ever operationalised they would represent the reversal of the heart of our ethics, that we protect the weak. They would represent the reversal of our health practice, that we treat the sickest folks first.

During the past week I have spoken to a range of physicians. Each has said to me they have never refused a patient treatment on the basis of age, and never been in a situation, within Australia, where they could not offer treatment to a sick person because of resources.

A distinguished cardiologist set out a hypothetical situation for me. Imagine there is a hospital with a team ready to conduct an emergency heart angioplasty. Say two ambulances arrive simultaneously. One contains a 60-year-old woman, the other a 40-year-old man. Both have had heart attacks. The hospital would of course treat them both. But normal practice would be to treat the woman first because, being 60, she is likelier to die than the 40-year-old man. But undeniably the 40-year-old man statistically probably has more life years ahead of him than the 60-year-old woman, even more so-called “quality adjusted life years”.

Ian Meredith is one of Australia’s most distinguished clinical and research doctors. (Full disclosure: I was his patient for a time). He is now global chief medical officer and executive vice-president at the giant Boston Scientific, based in Boston. I stole 90 minutes of his time this week over the phone and he told me in more than 30 years of practice he never refused a patient treatment because of their age, and he never chose one patient over another because there weren’t resources to treat both.

It is always a case of assessing each patient individually and asking what they want when they have all the information, and assessing if their general health is such that they would benefit from the treatment, and if the pain or danger of the treatment is worse than the disease. Age is obviously a factor in their general health but age itself is never a determinant.

This week I have asked this question of a half-dozen brilliant and experienced physicians. They all gave me a version of Meredith’s answer.

But the support for a “don’t worry too much about the elderly” approach is quite widespread. Lionel Shriver, a writer in her 60s whom I generally admire, argues in The Spectator that, based on her age, “Protecting the lives and livelihoods of young people is more important than protecting the lives of people like me”. That’s a heroic position for Shriver to take individually, but it’s still wrong. It classifies one category of human life as inferior to another.

Texas Lieutenant-Governor Dan Patrick said older people would rather die than hurt the US economy. Right-wing broadcaster Glenn Beck argued all people over 50 should go back to work, even if they all get sick.

There is a crude and really deeply anti-human economism at work in much of these arguments. The economy is immensely important. It is the basis of modern affluence. Resources, even medical resources, are not unlimited. One research program is funded at the expense of another and so on. But it is an entirely different and radically destructive, profoundly anti-human move from that to the assertion that one human being is intrinsically less worthwhile than another.

The marginalisation of the old in our society — casting them only as a burden and ignoring the richness of their lives and their inherent human dignity — is an evil trend much abroad already.

It is often argued that we spend too much money on people in the last five years of their lives. But of course we spend medicine on sick people. What a surprise. It’s a good thing. It’s human solidarity. FLASH NEWS BULLETIN: doctors treat the sick.

Our health system does assist our economy, but it is not altogether about economic values. It is primarily about human values.

Economism can go too far. Jonathan Swift’s Modest Proposal in the Irish famine suggested, satirically, that the best policy would be for poor people to sell their babies to be eaten, solving overpopulation and hunger, and preventing babies from being a burden.

More benignly, Yes Minister famously had a hospital win a national award for hygiene. But it was a hospital that had no patients, which meant of course it worked very efficiently and had excellent results.

There are two criteria for being treated in a hospital to the best of the hospital’s ability: being human and being sick.

Old people, even very old people, are abundantly and gloriously human. That’s all that counts.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout