Coronavirus: A level playing field for schoolchildren?

Over 100 countries have closed schools impacting 850 million students. But Scott Morrison says there’s no need.

It started with a ban on large outdoor gatherings; no more football games, concerts, food festivals or street fairs. Now the libraries, museums and cinemas are closing, social and junior sport seasons have halted, fun runs and gym classes are out, even Friday prayers at mosques are a no-go.

Life as we know it has stopped in the aim of achieving “social distancing”, a term few of us except the most committed introverts would have heard until recently.

But not schools. Those institutions of learning — where hundreds of students, in many cases more than 1000, pile in five days a week, seated shoulder-to-shoulder in close quarters, sharing equipment and supplies, bumping into each other in the hallways and playing tag in the playground — have been advised to remain open.

It’s been a tough sell for the health experts and politicians charged with getting the message across. Unveiling tough new crowd-control measures on Wednesday, Scott Morrison pointed out that he was happy to comply with official advice. “As a father, I’m happy for my kids to go to school,” the Prime Minister said.

“There is only one reason your kids shouldn’t be going to school and that is if they are unwell.”

Yet schools across the country are reporting significantly reduced attendance as parents, fearing their children will catch the potentially deadly coronavirus if they continue to attend school, keep them at home.

Teachers are also anxious and many are angry. On social media, where teachers have a robust presence, they vent about being used as babysitters, accusing the government of sacrificing them and their health for the nation’s economic interests.

As teachers unions have rightly pointed out, there is a contradiction between banning large public gatherings and insisting teachers and children mingle in close quarters for up to 30 hours a week.

Mass gatherings

NSW Teachers Federation president Angelo Gavrielatos estimates that 30 per cent of schools have more than 500 students, with the state’s largest public school having a population in excess of 2000 students.

“Schools have been told to implement a range of social distancing measures, which include keeping a distance of 1.5m between persons and minimising physical contact where possible,” Mr Gavrielatos said this week.

“However, the design of many of our schools and the size of our classrooms make this impossible.”

School administrators have been told they can help to minimise the risk of COVID-19 transmission by implementing strategies to restrict physical contact between staff and students. They’ve been told to cancel all non-essential activities, including assemblies, excursions, camps, school sports, even parent-teacher interviews.

Playgrounds have been rearranged, and recess and lunch times have been staggered to reduce large groups congregating.

It’s not been easy. As any primary teacher will attest, small children love hugs. Plus, with their clumsy hands and roaming fingers, they are still learning the basics of personal hygiene.

There have been reports of kids playing coronavirus-themed tag in the playground, while one Victorian secondary school had to sternly remind its students this week of acceptable behavioural standards after learning some older children had been deliberately coughing and spitting on others.

Rising anxiety

According to NSW Primary Principals Association president Phil Seymour, anxiety within schools is rising. Principals are being bombarded with questions and complaints from teachers and parents concerned that the virus could spread through the school; and that staff and children would become sick and infect those at home, including elderly and vulnerable family members.

“They feel like they’re being thrust on to the frontline of this thing,” Mr Seymour said

As the head of Sydney’s 150 Catholic schools pointed out on Tuesday — before apparently being pulled into line by the national Catholic schools body — many parents are ignoring the government’s advice and keeping their children at home.

More broadly, parents appear split. The Australian conducted a Facebook poll on Wednesday asking people if they felt comfortable with schools remaining open.

Although the poll continues, more than 3600 people have voted — 55 per cent say they are comfortable with schools remaining open and 45 per cent say they are not.

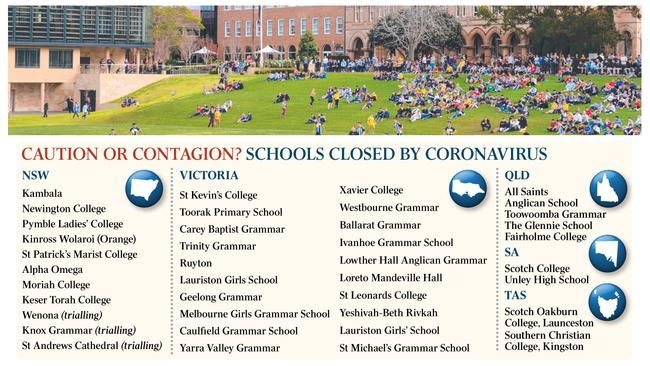

According to UNESCO, 102 countries have closed schools and educational institutions nationwide in response to this pandemic, impacting more than 849.4 million young people. Closures in Australia have been limited to a handful of schools that have reported COVID-19 cases, or close contact with cases, as well as a growing list of mainly metropolitan independent schools that have the resources and capability to send students home to continue their learning online.

Digital classrooms

One of the latest to close its doors, Kambala girls school in Sydney’s affluent eastern suburbs, assured parents it was in the fortunate position of having “an effective learning management system” that would enable remote learning.

“This is not the first time the school has faced such issues,” it said, in a statement to parents, noting that the school closed for a period in 1919 to counter the influenza epidemic of the time.

“Necessity is the mother of invention and through the school’s remote learning systems we remain true to, and confident in, our vision of inspired learning, and empowering young women of integrity.”

While reports of COVID-19 transmission in schools remains low, there are social, educational and economic benefits to keeping schools open. The Australian Health Protection Principal Committee, whose membership includes chief health officers from the states and territories, met recently to consider school closures in relation to the community transmission of COVID-19. The committee’s most recent advice to government was that “pre-emptive school closures are not likely to be proportionate or effective as a public health intervention to prevent community transmission of COVID-19 at this time”.

As Victorian Chief Health Officer Brett Sutton says, for pre-emptive school closures to be effective, prolonged closure is required and “it would be unclear when they could be reopened”. “If there were still a large pool of susceptible students when schools are reopened, there would be likely to be re-emergence of transmission in the community,” he says.

Mr Morrison spelled this out on Wednesday. “Whatever we do, we have to do for at least six months. That means the disruption that would occur from the closure of schools around this country, make no mistake, would be severe,” he said.

High economic cost

A report on social distancing on the federal Health Department website makes clear that while school closure was “moderately effective” in reducing flu and delaying the peak of an epidemic, “this measure is associated with a very high economic cost and social impacts”. “School closures should therefore be considered only in a severe pandemic and for the shortest duration possible,” it says.

“Individual school closure can be as effective as entire school-system closure. A limited duration of closure would be acceptable to the Australian public, especially if it was reactive rather than proactive, but it is likely that most children will continue to make contacts through outdoor activities during the period of closure, which may negate some or many of the benefits expected to be achieved.”

Appearing at the National Press Club on Wednesday, Doherty Institute director of epidemiology Jodie McVernon defended the government’s current stance, albeit acknowledging that it was a “hot-button topic”.

“The intentions behind the advice were clear … reducing the mixing with other non-vulnerable people and the fact that children are not actually experiencing severe infection and can probably be better managed in their social contacts in school under supervision than they would be out of school,” said Professor McVernon.

“In Singapore, schools have continued and they’re managing to contain their epidemic with a strong emphasis on maintaining continuity.”

It has been estimated that up to 45 per cent of parents could be taken out of the workplace to take care of children in the event of mass school closure. Many will call upon other family members, such as ageing grandparents, to pick up the childminding.

It is almost universally the schools in wealthier suburbs that have taken the jump to closing campuses and switching online.

A notable exception to the government’s advice related to boarding schools, which were seen at a higher risk of spreading the disease. Many of the independent schools which have closed in recent days already had the digital infrastructure in place to send their kids home to access curriculum. One of those schools trialling remote learning is Wenona, run by highly regarded principal Briony Scott. (Ironically Dr Scott is married to NSW Education Department secretary Mark Scott, who has been the public face of the state’s decision to keep public schools open.)

The North Sydney girls school has been sending different cohorts of students home each day to continue their learning remotely as part of the trial.

“It is a way of testing whether we can deliver what we think we can, and to iron out things that don’t work, while we can,” Dr Scott says. “We’re not switching to remote classes yet! But if we need to, we want to be ready.”

According to Dr Scott, the school community has been “legendary”. “They’ve been reading and watching, and juggling the different opinions, even within the medical profession,” she says.

“They recognise the complexity of the situation for everyone — not just their children or their family. I could not be more grateful for the support, the advice, and the guidance of experts in this field, and for the encouragement of parents who appreciate the challenges.”

The University of Wollongong’s school of education head Sue Bennett says a system-wide move to remote digital learning poses a significant challenge for the education sector.

Schools vary greatly in their access to technology, as well as the expertise of their staff, she says.

Then there’s the assumption that kids are surrounded by technological devices at home, when not all are. “A lot of my work has been around debunking this idea of the digital native; that all young people love tech, that they use it all the time,” Professor Bennett says.

“That’s just not the case, we can’t assume that all young people are skilled with tech.

“So one of the key concerns about these potential changes will be the equity issue and what we can do to address it and help out those vulnerable students.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout