Communities overruled as Victoria puts all its eggs in the onshore renewables basket

The Victorian government’s new planning fast-track for renewable energy projects has residents fearful the renowned Heathcote wine region is about to become home to Australia’s largest solar farm.

Almost exactly two years ago, the Victorian government released a policy directions paper that stated that meeting its net-zero targets using onshore renewable energy generation “could require up to 70 per cent of Victoria’s agricultural land”.

The government has since distanced itself from the assertion – which has been rubbished by energy industry experts as an “embarrassing” attempt to justify plans to invest in more expensive offshore wind generation – and removed the paper from the state Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action’s website.

However, the claim continues to serve as an inconvenient reminder of the degree of difficulty Victoria faces in seeking to meet its target of 95 per cent renewable energy by 2035.

As The Australian has reported in recent weeks, energy experts from across the ideological spectrum are predicting that Victoria’s offshore wind targets will take longer to meet and be significantly more expensive than the state government estimates.

This has been compounded by the dual setbacks of federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek vetoing the government’s plans to use the Port of Hastings to assemble and transport turbines, and a reduction in the Southern Ocean wind zone to 20 per cent of the area originally proposed amid concerns over whale habitat.

With 62 per cent of Victoria’s energy currently derived from fossil fuels, and the state one of the nation’s most coal-dependent, it is running out of time to find alternative means to keep the lights on before its brown coal-fired generators switch off. The Yallourn coal-fired plant, which supplies about 22 per cent of Victoria’s electricity, is due to close in 2028.

Adding to the imminent challenge of ensuring the availability of reliable, dispatchable power is a looming gas shortage, as highlighted this week by the Australian Energy Market Operator in its annual Victorian Gas Planning Report.

AEMO has predicted possible shortages as soon as next year, warning that gas-fired generators could be forced to burn diesel to keep the grid running. In unusually frank comments, the market operator attributed the looming shortfall to a lack of investment in new supply, as production from Bass Strait – which historically has supplied about two-thirds of southern Australia’s gas – continues to decline faster than demand.

“Many potential projects identified in the 2023 VGPR have not materially progressed due to regulatory approval requirements, difficulty acquiring financing for natural gas projects, and market participants’ resistance to making long-term commitments in an uncertain investment environment,” AEMO stated on Thursday.

The most significant factor contributing to that “uncertain investment environment” is the Allan government’s Gas Substitution Roadmap, which aims to encourage Victorians to shift from gas to electricity, including through a ban on gas connections to new homes that began on January 1.

The imminent closure of coal-fired generators, impending gas shortage, increasing demand for electricity as the government encourages the electrification of homes and vehicles, challenges in establishing an offshore wind industry and the government’s determination to reach its renewable energy targets all add up to an insatiable demand for investment in onshore solar and wind.

Enter Premier Jacinta Allan’s announcement last week that from April 1 her government will fast-track planning approvals for renewable energy projects, removing the right of third parties to appeal to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal, and concentrating power in the hands of Planning Minister Sonya Kilkenny.

The minister will be advised only by a specialist team of in-house bureaucrats whose primary objective will be to ensure applications are approved or rejected within four months of receipt.

Communities objecting to projects in their vicinity will be able to appeal to the Supreme Court only on a point of law, with no grounds for appeal on a policy or planning basis. The same rules already apply to development of schools, hospitals and projects that form part of the state government’s “big housing build”, under what has been dubbed by the “development facilitation pathway”.

Earlier this week, RMIT University environment and planning emeritus professor Michael Buxton told Inquirer the new regime would lead to “terrible decisions”, with wind and solar farms being “placed in the wrong locations”, cementing Victoria’s reputation for having the “most radically centralised and autocratic model of decision-making in the country”, with negative consequences for biodiversity, farmland and Victoria’s landscape.

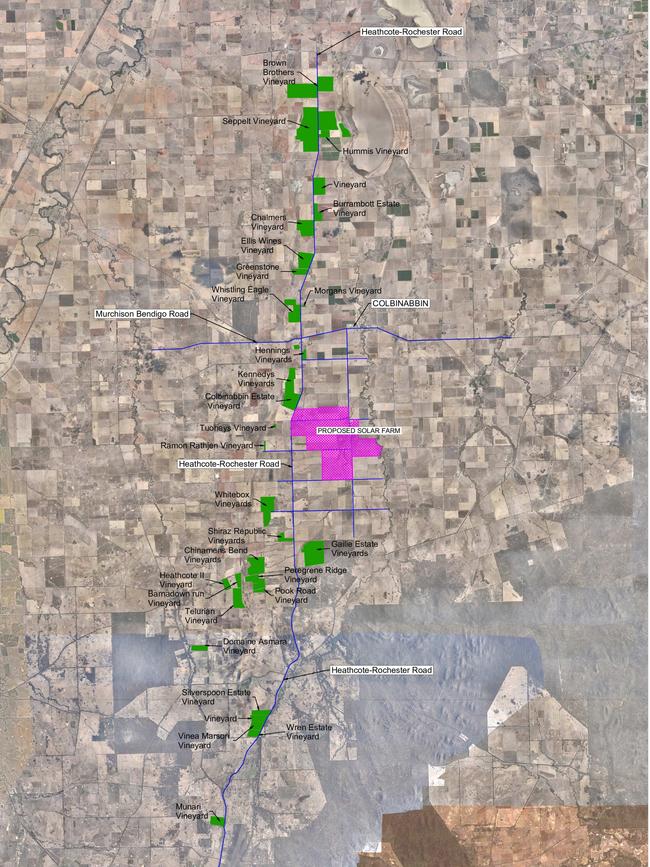

It is a view shared by the Colbinabbin Renewable Action Group, which represents about 60 businesses, farmers and residents in the heart of the Heathcote wine region in central Victoria, where multinational renewable developer Venn Energy is planning to construct what would be Australia’s largest solar-powered plant, taking advantage of the site’s proximity to major overhead transmission lines.

“This is political bullying by an arrogant government that has zero tolerance for alternative views,” says spokesman John Davies. The more than 800ha Cooba Solar Farm being proposed by Venn Energy, which has headquarters in Canada and directors in Turkey and Afghanistan, is being considered by the state government.

Davies, who with wife Jenny owns the 60ha vineyard Colbinabbin Estate, says locals initially had been hopeful of a fair hearing for their case against the project, which would be located on some of Victoria’s most productive agricultural land.

“State planning guidelines prioritise the protection of productive agricultural land, and when you have a look at the land in question, it’s not only productive, it’s highly productive – it’s another step above merely productive agricultural land.

“Then you add that there’s a community irrigation pipeline that connects most of the properties all along the Mt Camel range, including the proposed location of the solar plant, and you add reliable quality water to highly productive land, and that converts it into strategically important land.”

Land adjacent to the solar farm recently sold for almost $20,000 a hectare – testament, Davies says, to the fact this “isn’t just normal flat-land grazing country”.

The proposed solar farm is also located in the middle of the Heathcote grape-growing geographic indicator, meaning Wine Australia has assessed the fertile Cambrian volcanic soil as being highly suited to intensive viticulture.

“Do you think a 2000-acre solar factory would be allowed to be established in the middle of Bordeaux or Burgundy?” Davies asks.

“The wine industry and wine tourism have been identified as being strategically important growth industries. The solar factory will have a catastrophic impact on the views and amenity of this iconic wine region.”

Davies says when he and his neighbours first examined the state and local government planning guidelines, they believed they had a strong case for appeal.

“And we had confidence in the independence and authority of VCAT to ensure that the state planning guidelines were followed.

“But we now feel that the calling-in process means the minister doesn’t have to follow any advice. The only avenue for appeal is on a point of law to the Supreme Court, which is beyond belief in fulfilling natural justice.”

Buxton says the Colbinabbin community’s concerns reflect those of community groups, farmers and environmentalists all over the state. While the largest projects and those being built in particularly environmentally sensitive areas will be required to undergo an environment effects statement and be subject to third-party submissions, Buxton says he is not at all reassured that the EES process, conducted through the Planning Minister’s office, will provide communities, ecosystems and landscapes with adequate protection.

He recently has examined the EES for the massive 16,000ha Golden Plains wind farm, 70km northwest of Geelong, which is set to become home to 278 turbines, each with a height of 230m.

“They identified all these serious environmental impacts, but said they could be offset,” Buxton says. “So there’s all these vulnerable species, but it doesn’t matter because you can go and buy offsets somewhere else, which is never going to make up for it.

“The other really worrying thing they said was that yes, there are serious environmental impacts, but these should be balanced by the social and economic benefits. So what they’re doing is basically saying it doesn’t matter that the environment is trashed, so long as they meet their renewable energy targets. It’s nonsense. The incremental, relentless loss of habitat and landscape from each of these projects will add up to really major environmental loss and destruction. It’s insidious.”

Buxton says the government should be using commercial, industrial and retail sites for rooftop solar generation.

Victorian Farmers Federation president Emma Germano says the Cooba Solar Farm proposal is among countless examples of projects planned for prime agricultural land.

“How many of these projects have to be put in inappropriate places that completely conflict with the use of the land for food production before the state government realises it has a serious problem?” Germano asks.

She says arable land makes up just 4 per cent of Australia’s land mass. “And here we are putting renewable developments on this precious resource rather than considering how we utilise the vast, barren space in the middle.

“Food and fibre is the biggest export out of Victoria, the state is going broke, and yet here we are threatening that industry because of poor planning and a mad rush to an arbitrary target. This government has rocks in its head,” Germano says.

“The government can see the increasing objection to these inappropriate projects, and yet its latest move was to ensure that more inappropriate projects can be built, without giving two hoots for the communities they affect.”

A Venn Energy spokeswoman says the company welcomes the Victorian government’s decision to fast-track planning decisions on renewable projects.

“Such a process would greatly assist in achieving the state and federal governments’ renewable energy targets,” the company says. “While further details are still to be released from the Department of Transport and Planning, Venn believes that neighbours and the community will still have an opportunity to provide input during the planning process.”

The spokeswoman says the Cooba Solar Project planning application will be made public as part of the planning process “and is supported by specific studies, comprehensively addressing questions around agriculture, visual impact, hydrology, biodiversity and more”.

“Venn’s consultation with the Colbinabbin community is ongoing, and we will continue to meet with relevant community members throughout this process.”

A state government spokeswoman says there is no change to the public notice process for permit applications for renewable energy projects. “Notice will still be given of all permit applications, and neighbours and community members will be able to formally object to the project,” she says.

It remains to be seen how much sway those objections will hold with a minister who has every incentive to ignore them in her government’s desperate push to meet renewable energy targets.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout