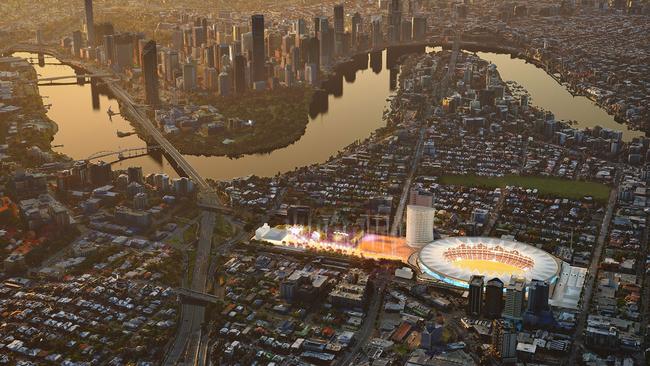

Commonwealth Games cost debacle has implications for Brisbane 2032 Olympic Games

Don’t be fooled by claims that Daniel Andrews’ hatchet job has no implications for Australia’s third Olympics. The experience to date with the Gabba hardly inspires confidence.

But any sense of complacency – that it was business as usual for the organisers – bit the dust this week after the Victorian government did the unthinkable and canned the next biggest multi-sports tournament going, the 2026 Commonwealth Games.

Don’t be fooled by claims that Daniel Andrews’ hatchet job has no implications for Australia’s third Olympics. The Victorian Premier’s rationale that the Commonwealth Games were “all cost and no benefit” on the back of a $4bn-plus blowout in the state’s projected spend will shake confidence in the Brisbane set-up if costs there also balloon.

History says there is every chance this will happen.

And yes, the Olympics are a step up in size and complexity, with 11,500 athletes attending pandemic-delayed Tokyo in 2021, against 4426 for the 2018 Commonwealth Games on the Gold Coast. Yet arranging and managing these events are broadly similar propositions. The influx of competitors, officials, media and paying visitors must be accommodated, world-class venues laid on, transport links provided, security put in place.

Brisbane 2032 also shared with Victoria 2026 the cost engine of a regional footprint.

The Olympics will unspool across southeast Queensland – volleyball, weightlifting and the triathlon devolved to the Gold Coast, basketball and road cycling to the Sunshine Coast, soccer in Toowoomba as well as Townsville, Cairns, Sydney and Melbourne – vulnerable to the cost pressures that mugged Andrews – if you accept his account of what transpired, which Commonwealth Games Australia certainly doesn’t.

Businessman Andrew Liveris, the moustachioed president of the organising committee for the Brisbane Games, OCOG, says the Victorian decision was shocking and “not a good look for Australia”.

Still, he is adamant that the funding models are very different: corporate sponsorships, a richer ticket base and the best part of $1bn kicked in by the International Olympic Committee from broadcast rights mean that, operationally, the Olympics can be cost neutral.

Echoing the assurances provided this week by Anthony Albanese and Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk, Liveris tells Inquirer: “The Commonwealth Games business model, as I understand it, involves very, very different types of funding … there’s no application at all. We’re full steam ahead.”

There’s a disclaimer, however. The $4.9bn in costings detailed in Brisbane’s successful bid to the IOC and associated Host City Contract cover the running expenses such as security, hospitality and setting up the three athletes’ villages, not investment in venues and transport infrastructure brought on for the Games, providing much of the vaunted legacy for all those taxpayer dollars sunk into them.

While the Prime Minister and Palaszczuk have agreed to split a $7bn bill to construct or upgrade stadiums and sports halls, there is growing unease about the lack of clarity around the other capital works. Queensland Opposition Leader David Crisafulli demanded on Wednesday that the Labor governments get together to list the priority projects.

The experience to date with Brisbane’s Gabba stadium hardly inspires confidence.

The inner-city ground will be Olympic HQ, site of the opening and closing ceremonies as well as the athletics competition. More than $160m in new stands and refurbishments across the past two decades have lifted the capacity to 42,000 for cricket and the AFL, but the proposition that the creaking facility has passed its use-by date is generally accepted.

A dearth of amenities for women and unresolved issues with disabled access top the to-do list. The cost cited by Palaszczuk in 2021 to bring the Gabba up to scratch and expand the seating to 50,000 was $1bn, which the then Coalition government in Canberra under Scott Morrison would share in a 50-50 funding agreement for the Games as a whole.

Fast forward to February this year when Albanese, the 2022 election victor, stood up with the Premier in Brisbane to announce a revised deal. Demolishing and rebuilding the stadium was to now cost an eye-watering $2.7bn and the project would become a Queensland responsibility, while the federal government picked up the tab for the $2.5bn Brisbane Arena to house the Olympic swimming in a drop-in pool. Another 16 venues would be revamped with the remaining $1.8bn in shared funding.

Palaszczuk is yet to explain the Gabba blowout beyond saying, unconvincingly, that it was a function of post-Covid construction inflation. Queensland Auditor-General Brendan Worrall gave a more persuasive answer: the original price tag was unverifiable given no business case could be turned up, he revealed in March. In fact, the evident source of the $1bn estimate was a government press release.

Liveris, 69, won’t touch the criticism of Palaszczuk being fast and loose with the Gabba numbers, at least in the first instance.

Darwin-born and a graduate of the University of Queensland, he’s the former chief executive and chairman of US industrial giant Dow Chemical who professes to have brought a boss’s eye for the bottom line to the Olympics role. So what would he have said to his old corporate team had they tried to sell him on a project that exploded in cost by 170 per cent in under 18 months?

“Well, that has happened to me,” Liveris replies. “My reaction would be very clearly to ask, have we got the right scope and have we got a right view to the economic returns of that span? And, similarly here, you’ve got to understand that … one year, two years later, when you get people looking at what has to be done and what the cost of the entire project is, you will get a new estimate and that new estimate has a lower error band. The fact that it’s gone north, not south, is no shock.”

He is circumspect when asked to comment on the axing of the Commonwealth Games. Was it justified? Should Andrews have tried harder to save the event? “If there’s no source of funds and it’s blowing out to that extent … really, they had a financial breakdown in their business model,” Liveris says. “But that’s all I know.”

He agrees that cost-of-living pressures are biting through price inflation and the resultant interest rate hikes here and abroad, though the prospect of a recession in the US is no more than 50 per cent and even then would involve a “soft landing”.

The upshot is that the macroeconomic environment is far tricker than it was 12 months ago when he was named to head OCOG.

Between that role and board gigs with state-owned oil producer Saudi Aramco, IBM and electric carmaker Lucid Motors, Liveris found time to write a new book, Leading Through Disruption, styled as a tour d’horizon of climate change, economic downturns and geopolitical upheaval in the 21st century. It has helped him identify big-picture opportunities for the Games.

Take the supply chain disruption that emerged as a result of Covid and ongoing tension between the US and China. Liveris says this has compelled companies and governments globally to rethink logistic networks and shift to onshore manufacturing, something Brisbane 2032 can leverage.

On cue, Palaszczuk marked Friday’s second anniversary of the Games being won by unveiling a strategy for local businesses to tap into the $20bn spent annually by the Queensland government on procurement. “I’m very much wanting to take advantage of these new macros that are causing companies to locate to safe or less risky jurisdictions,” Liveris says.

Benchmarking OCOG’s progress to date, he says his first year in the chair was about “listening” – to his counterparts in Paris at the pointy end of delivering next year’s Olympics, to those in LA, next cab off the rank in 2028 and beneficiary of an extended runway matching Brisbane’s; to the Queensland and federal governments, of course, Brisbane City Council and stakeholder regional municipalities; to First Nations representatives, an important constituency for him; to the IOC, the Australian Olympics Committee as well as Paralympics Australia; and, not least, to Olympic athletes and the various sports federations.

He has met Crisafulli and takes on board the criticism the Queensland LNP leader has levelled at Palaszczuk and Albanese over the pace of infrastructure development for the Games, a frustration shared by industry think tank Infrastructure Partnerships Australia. Issuing a hurry-up, chief executive Adrian Dwyer has said: “The 2032 Olympics infrastructure needs to be delivered in the context of an existing $96.5bn forward pipeline yet to begin delivery – that’s a huge task and it needs a co-ordinated approach.

“It is essential that there is an integrated transport plan for the 2032 Olympics – the most decentralised Olympics ever delivered – that focuses not only on venues but also connections between them. Key projects like the Beerburrum to Nambour Rail Upgrade (on the Sunshine Coast), Logan to Gold Coast Faster Rail and the Coomera Connector (motorway) must be progressed so that athletes aren’t playing to empty stadiums outside of Brisbane.”

Seizing on the debacle in Victoria, Crisafulli renewed a pledge to reinstate the independent Olympic Co-ordination Authority that was proposed in the Brisbane 2032 bid to oversee the infrastructure program but dumped by Palaszczuk with the backing of IOC powerbroker and former AOC president John Coates. The LNP man didn’t mince his words in demanding a plan to bring in projects on time and on budget.

“There has been no discussion about roads and rail and housing and water and a 20-year tourism vision from the state government. Nothing since the Games have been secured,” he said on Wednesday.

Liveris is appealing for the critics and sceptics to be patient. It’s still early in the countdown, he says, and the New Norm approach mandated by the IOC to make the Olympics more affordable and beneficial to the host city or region requires new thinking.

Better to be measured and “front load” the difficult decisions, like big business does. Scope definition is critical. “We have to be very, very careful that we don’t add to the scope, that we don’t have the scope creep,” Liveris explains from LA, en route to Brisbane for this weekend’s “nine years to go” festivities. “We don’t want to make this, you know, literally bigger than all outdoors because that’s a recipe for disaster.”

As we report in the news section, his nomination of nuclear power from cutting-edge small modular reactors as part of the prospective energy mix to deliver the first “climate-positive” Games shows he is prepared to ruffle feathers; neither Albanese, a product of the Labor Left, nor the ever-cautious Palaszczuk is likely to thank him.

And it’s not the only unconventional idea Liveris has to cut costs and boost “optimisation”. He likes a suggestion by Coates to limit how long athletes can stay in village accommodation: “Does every athlete need to come for two weeks for the two sets of Games? Or can we just bring in athletes for their timeframe and have them leave?”

In the same vein, Liveris wonders whether a vast and expensive broadcasting centre is really necessary in the digital age. His chief executive at OCOG, Cindy Hook, is exploring the proposition with the IOC. Watch this space, he says, as advanced technology including virtual reality will feature heavily in Brisbane.

Lord knows that after this black week for Australia’s reputation as a sporting nation a little sunshine is entirely in order. This country held two outstanding Olympics in Melbourne in 1956 and Sydney in 2000, and Liveris’s upbeat message is there’s no reason the three-peat can’t be achieved at Brisbane 2032.

“We will completely overcome any negativity that might have come out of that,” he says of the collapse of the Commonwealth Games. Here’s hoping.

When Brisbane secured the right to hold the 2032 Olympics two years ago, time was very much on its side. The Queensland capital joined Los Angeles in having the luxury of 11 years to plan and prepare.