Climbers fight for right to higher ground

Parks Victoria has vastly overstated the impact of cultural and environmental damage at national park sites amid fresh doubts about the campaign against Australia’s rock climbers.

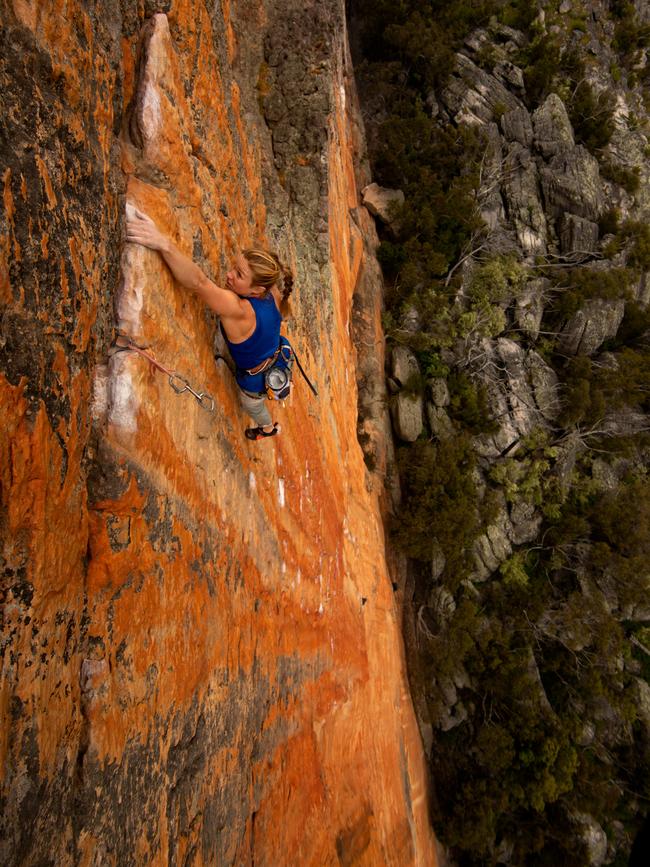

For months men and women with clipboards, hard hats and hi-vis jackets have been quietly deliberating among the cliffs in the back blocks of the Grampians National Park, low-key participants in what has become Australia’s seminal public land access dispute.

With specialist surveying tools, the groups have been examining the environmental and cultural heritage impacts of well over a century of white Australian influence in a grand bush setting known to Aboriginal tribes for 22,000 years.

It is widely accepted that Parks Victoria and its predecessors have dropped the environmental ball in recent decades in the outer areas of the park, allowing the Grampians to be degraded by vandalism and at times cavalier behaviour that has alarmed indigenous and green groups.

However, just who committed much of the harm is wide open to debate, given the cross-section of people who visit the park every year from local towns, cities and overseas, arriving on foot, motorbikes, four-wheel drives and even from the air.

At the same time, Parks Victoria has picked an unprecedented fight with the Australian rock climbing fraternity, which has broad implications for recreational access to national and state parks across the country.

The impact, while not as symbolically significant as the end of climbing at Uluru, has the potential to snowball across Australia’s parks, ski fields, mountain biking tracks and climbing theatres as greater power is handed to indigenous co-managers.

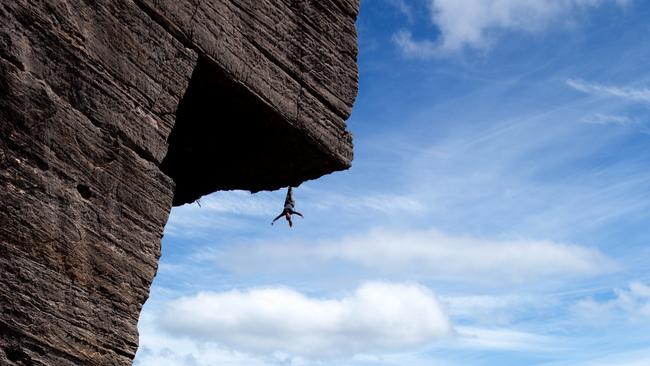

With workers in the final stages of surveying large tracts of the Grampians land, Parks Victoria and the traditional owners are planning what sort of access climbers and others will have to the area, potentially maintaining or even widening the effective climbing ban on 500sq km of the park.

Within the current ban areas lie some of the world’s best rock climbing sites. Local businesses such as Mount Zero Log Cabins in the northern Grampians are reporting dramatic cuts in revenue, in the order of 25 per cent.

“I’ve got to tell you, I was a bit pissed off about the way Parks Victoria went about it,’’ businessman Neil Heaney tells The Weekend Australian. “They are picking on the wrong people … They (the climbers) are deeply respectful people.’’

There is broad acceptance in the climbing community that there is capacity for its members to overhaul some practices and a willingness to help address core issues such as the undermining of vegetation and the need to remove chalk remnants in key areas.

‘Smear campaign’

But there is also growing concern that the Parks Victoria narrative has been bolstered by a series of legally unverifiable, anti-climbing claims that included the false assertion that a climbing bolt had been put through art. In fact, it was past government workers who desecrated the site.

Valid questions are being asked about whether Environment Minister Lily D’Ambrosio has been accurately briefed about who is responsible for the most serious harm and whether or not climbers are victims of an excessive spin campaign.

Simon Carter, a climbing photographer with a global following, believes climbers are victims of a sophisticated campaign of vilification. “I believe climbers have been scapegoated to distract from far, far more serious impacts that are occurring to the cultural and environmental values of the park, appalling mismanagement and a sneaky move towards the commercialisation and commodification of our national parks,’’ he says.

“The legal determination behind it (the climbing bans) is based on observations and research undertaken at other locations, not based on anything that has actually occurred in the Grampians.

“Rock climbers have been wrongly vilified by parks staff or consultants in what I can only describe as a smear campaign based on absolute falsehoods.

“For example, rock climbers were accused of placing safety bolts into Aboriginal rock art. Climbers had done no such thing, not even close, but then Parks published a ‘bolt-in-rock-art’ photo on its website as some ‘evidence’ of climbers’ impacts. But the bolt had been placed by land managers, not climbers. It was a fabrication.

“And photos sent by Parks Victoria in briefing papers to the Minister for the Environment show chain-sawing of trees, fireplaces and other impacts that almost certainly had nothing to do with rock climbers.’’

Evidence doubts

Last March D’Ambrosio was sent a series of photographs from Parks Victoria chief executive Matthew Jackson purporting to show evidence of climber damage, except many of the photos Jackson sent to his minister failed to meet any serious legal test. Instead, what D’Ambrosio received was a series of pictures in which environmental harm had occurred, but with no actual proof of who committed the harm.

Yet this was crucial timing, occurring when the government had doubled down on the climbing community.

While different scenarios, the incident is similar to the photographs released by the Howard government in 2001 during the children overboard crisis. In this, there were photos showing that something had happened, but no serious evidence that supported the government’s narrative.

Of the eight images sent to D’Ambrosio, only one shows verifiable harm by climbers; this is of persistent use of chalk at one location to help people negotiate a climbing route.

No one would doubt this as climber damage; the rest show a fireplace with nobody around it, a log that had been cut with a chainsaw by an unknown person and some stone stacks created by someone who is not in the picture.

Several other images are of damage to vegetation at Venus Baths, near Hall’s Gap, which has become a popular site for the climbing discipline called bouldering.

What should have been articulated to the minister is that Venus Baths also happens to be one of the most visited tourism hot spots in the Grampians, three hours’ drive west of Melbourne. It is an easy walk for parents with young families, who have trampled through the area for many decades because it is in close proximity to the main town in the park.

Without addressing specific questions on the accuracy of the photographs showing climbing damage, Jackson said in an email: “Information and updates are regularly provided to the Minister for Environment as per standard briefing processes.’’

On the question of who is responsible for the damage, he said: “Parks Victoria has continually provided updates on direct recreational impacts in the Grampians to members of the rock climbing roundtable, including updates from independent experts of the impacts of rock climbing at sensitive rock art sites.

“Parks Victoria has specifically informed members of the rock climbing roundtable that not all recreational impacts are caused by rock climbers.”

Assault on art

Parks Victoria has been savaged by climbers and some local businesses for the unilateral bans, which were imposed without any meaningful warning, partly on the basis that the Grampians contain as much as 90 per cent of the indigenous rock art in southeastern Australia.

The Grampians’ Mount Arapiles — Australia’s rock climbing mecca — has just had a major outcrop declared out of bounds because of unspecified cultural heritage discoveries. Taylor’s Rock is one of the cradles of rock climbing education in Australia and is a key part of the adventure sport economy that underpins the nearby Natimuk community, 330km northwest of Melbourne.

Ben Gunn, an archaeologist and rock art specialist who recently wrote a paper on the effects of climbing in the Grampians, says he has no doubt who causes the most damage in the park. He also acknowledges that much of the indigenous art can’t even be seen with the naked eye and damage may be inadvertent.

“With the explosion of rock climbers in recent years, it is they who currently pose the greatest human threat to cultural heritage sites within the Grampians National Park and surrounding sandstone ranges and potentially to other national and state parks elsewhere in Australia,’’ he wrote with several authors including Jake Goodes, brother of football great Adam Goodes.

Gunn has outraged climbers by claiming that some in their midst were behind graffiti in parts of the wider park; again, climbers want to see the proof of this to a legal standard.

“Much of the graffiti in the Greater Gariwerd (Grampians) has not been produced by rock climbers,’’ Gunn wrote.

“In other instances, particularly at Lil-Lil, it is all too apparent that rock climbers are at fault. At Lil-Lil, some graffiti has been deliberately placed over rock art and the damage is permanent.

“Others have been racially offensive or, through the production of pseudo rock art, deprecating to Aboriginal people and the majority of non-Aboriginal Australians.’’

Chalking, he wrote, was classed as damage comparable to graffiti. Whether this claim about chalking as graffiti passes the legal test is questionable, particularly if people do not know there is art where they are climbing.

Australian Climbing Association Victoria president Mike Tomkins is open to overhauling some climbing practices to protect indigenous art, but says accusations of climbers writing over art and carving words into rock walls are false and unverifiable. “You can’t prove it. You cannot pin that on climbers. All the locations have been visited before there were even climbers,’’ Tomkins says.

While the climbing community has been divided about how to deal with the crisis, there is deep angst about the way the pursuit has been characterised. Climbers have congregated for decades at the Grampians and Mount Arapiles has traditionally been strongly green and sympathetic to the indigenous plight.

Others are highly sceptical, also, about figures used by Parks to suggest an unprecedented rise in climber numbers in recent years, arguing that while there is an uplift in interest, Parks Victoria has greatly exaggerated the number of extra climbers by misreading the statistics.

Uncle Ron Marks, a Wotjobaluk elder with close ties to Mount Arapiles and the Grampians, has worked in cultural education for decades, teaching about indigenous history. He wants a pragmatic approach that protects heritage, but enables people to go about their business in the knowledge that at Mount Arapiles, for example, the indigenous connection is long-running.

He warns the “kerfuffle’’ affecting climbing at both locations is having a clear impact. “You look at it from a business point of view, people are suffering,’’ he tells The Weekend Australian.

Meanwhile, climbers are locked in a form of political purgatory, with no clear line of sight to when the ascension to higher ground will be guaranteed.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout