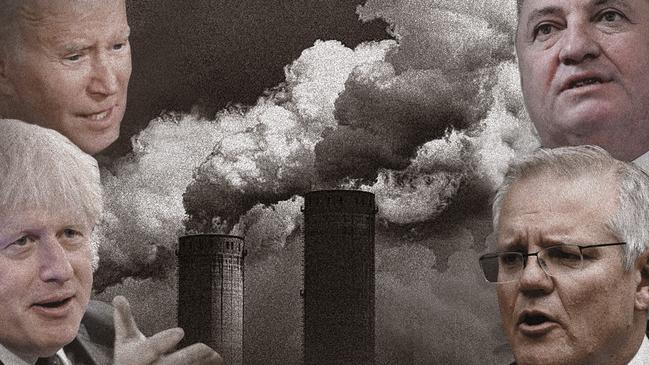

Climate of dissent has divided the world ahead of Glasgow climate summit

The future is on display – ambitious assurances in collision with entrenched domestic politics. Forget any notion that Australia is unique.

At home, US President Joe Biden is battling to secure his clean electricity bill through congress to avoid his embarrassment at Glasgow. The US is trying to persuade China’s President Xi Jinping – leader of the world’s largest emitter – to change his mind and attend. Leader of the world’s third-biggest emitter, India’s Narendra Modi, has just agreed to go. Russia’s Vladimir Putin representing the fourth main emitter is not attending, and nor is the darling of progressive opinion, New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern.

The host, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, has spent the past week talking up the UK’s climate change agenda while talking down expectations about Glasgow. “COP was always going to be extremely tough,” he said, referring to the 26th UN Climate Change Conference that is aiming to secure new and more ambitious emissions-reduction targets across the world.

While Johnson cast Britain as the leader of “the green industrial revolution” with the 10 policy commandments “that I brought down from Sinai last year”, government documents revealed the reality: new taxes from the transition, lower revenues, assessing mortgages on climate change criteria, road pricing, and more investment in nuclear power.

The British stake in Glasgow is huge. The royals feel saving the planet transcends their monarchical neutrality. Prince Charles said the threat to the planet “was already beginning to be catastrophic” and, desperate to become greener still, he had converted an old Aston Martin to run on English white wine and whey.

Prince William has criticised the space entrepreneurs, saying the world’s best minds must focus on repairing the planet not finding “the next place to go and live”.

Remarkably, the Queen’s frustration boiled over in an overheard comment: “Extraordinary isn’t it, still don’t know who is coming. No idea.” She’s right. It is extraordinary. But it reveals so much. The credibility of Glasgow is on the line. Climate action is a profoundly divisive issue and much of this political fracture is still between developed nation elites and the less better-off, both among nations and within nations. Opinion is moving in favour of action but don’t be fooled by the latest propaganda that net zero at 2050 is yesterday’s debate and grossly inadequate. There is no certainty this goal can be met. The changed living conditions and structural adjustment involved are huge; witness Bill Gates saying the 2050 target will be “the hardest thing humanity’s ever done” and getting the public to accept the necessary changes remains an unknown project.

The myopia in Australia’s debate is also extraordinary. Scott Morrison’s project has been to shift the Coalition parties onto a new position and consign the Abbott-Turnbull climate battles to history. While the Nationals should have faced this issue much earlier, net zero at 2050 is one of the toughest decisions they have faced in the post-war period. It was always going to be traumatic.

People lamenting this don’t have a grip of the real world. Perhaps they should ask why so many national leaders aren’t going to Glasgow and take a check on the internal divides running through so many countries.

Acting in the national interest and his party’s interest, Morrison had no option but to make the big shift. Having Barnaby Joyce as Nationals leader has been invaluable. But the backlash from the populist right will be fierce, suggesting a high minor-party vote at an unpredictable federal election.

Unless China steps up and plays a credible role, damage to the Paris Agreement will be accentuated. Climate outcomes depend largely on deals between the US and China, the two main emitters. But last month, China took a tough line with Biden’s climate envoy John Kerry, who wanted more ambition from Beijing. China, it seems, wants to be responsible, but its dependence on coal is immense and it runs linkage with the US – tying climate to other issues in bilateral relations.

Authoritarian leaders feel less need these days to follow global norms. Glasgow occurs against an ominous global landscape – the debilitation from Covid-19, rising populism, escalating geo-strategic tensions between the US and China, the tearing apart of the liberal trade order, mounting protectionism, and a new mood of introspection and self-reliance among nations. This threatens to usher in a new age of disruption and escalating nationalism.

The Covid-19 crisis saw the complete demise of effective international co-operation. China engaged in cover-up, deception and refusal to co-operate with the World Health Organisation. Donald Trump tried to play down the pandemic’s danger and repudiated any US global leadership role. The crisis became a stage for US-China rivalry.

The most serious global health crisis for 100 years saw a broken international system and a startling inability of leaders to operate on the principle of an interdependent world. This setting is the prelude to Glasgow. An optimist would hope leaders will not repeat the same climate change mistakes but a realist would be wary.

Country pledges remain voluntary but the story since the Paris Agreement has been leaders strong on pledges and weak on action. That’s because of fear of shock. China wants to use coal for longer, a signal recently coming from Premier Li Keqiang, at the same time as Beijing becomes supplier to the world of renewable energy tools, a nice win-win play.

Contrary to lectures from billionaires about how Australians must adapt, the transition for many people will be difficult, with many pitfalls. As The Economist stated: “Many countries have net-zero pledges but no plan of how to get there and have yet to square with the public that bills and taxes need to rise.”

Morrison is right to say the debate is about “how” but his road map, when released, needs to go far beyond the political construct of “technology, not taxes”.

Lobbying has been under way to persuade a number of leaders to attend at Glasgow. But it appears there are still no acceptances from the leaders of Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, India and Saudi Arabia. Current reports are that more than 120 leaders will attend, including Morrison. More conformations may come through. But the perception cannot be avoided – there are vast discrepancies across the globe on climate change priority.

If Glasgow fails or disappoints, the dangers are guaranteed to intensify. The upshot will be growing energy disruption and political agitation. The world has never been here before. Capital flows, banks and central banks will operate on the net-zero 2050 timeline. The risk premium on carbon-intense industry will rise, perhaps in a brutal and what many will interpret as an undemocratic way, while, at the same time, doors will open for investment in green energy opportunities.

Australian corporates are embracing the 2050 targets. In effect, Morrison is saying if Australia doesn’t move, it will be punished. Liberal and Labor act on this foundation. The two parties are being driven closer together by energy, financial and political forces. Net zero at 2050 will become the shared stance of Coalition and Labor at the election.

There will still be differences, probably, over the medium-term 2030 or 2035 targets. Morrison won’t lift his medium-term ambition. He will merely provide an update that, on current policy, Australia will exceed its 26-28 per cent target, coming in around 34- 35 per cent (showing how deliberately conservative the Abbott government’s initial decision was).

Such caution at 2030 is designed to save Morrison’s political life in the regions at the election – but that will still remain a daunting call. When Labor settles a medium-term target, it is likely to be higher but not too much higher than the Morrison-Joyce position. What is Anthony Albanese’s consistent tactic? Denying Morrison a scare campaign against him.

Australia’s debate is topsy-turvy, best symbolised by the realignment from the Business Council of Australia to embrace a 2030 emission-reduction target of 46-50 per cent. The Greens pocketed this win but neither Morrison nor Albanese will go near it.

Morrison’s challenge is to retain enough credibility with two rival constituencies: people in the suburbs who want action on emissions and renewables; and people in the regions who fear for their jobs and livelihoods.

The main parties need to pitch to both sides. This is where Morrison had the advantage at the 2019 election, with the Liberal-Nationals Coalition making it easier to send different messages to different constituencies from leafy Melbourne to regional Queensland. It will be more difficult to replicate this at the 2022 poll given the grassroots revolt Clive Palmer and Pauline Hanson will ferment.

If you thought Barnaby Joyce’s big test ends with next week’s announcement you could not be more mistaken. It is after the announcement that Joyce will face the most exacting test of his political life – having to explain and justify net zero at 2050 to his electoral base, with much of it sceptical or even hostile.

Morrison, meanwhile, is redefining the climate issue as an economic policy. Have you noticed he almost never mentions saving the planet, never invokes the “moral challenge of the age” and rarely talks about rising temperatures?

The entire purpose of Glasgow, of course, is to keep rising temperatures to below 2C above pre-industrial levels and try to achieve 1.5C. But Morrison knows nothing is more calculated to inflame conservative sentiment than green rhetoric about Australia’s global climate obligations when it contributes less than 1.3 per cent of total emissions.

Morrison is right to go to Glasgow and make his case but he will not satisfy the global climate audience. Meanwhile, the climate change schism between the developed and developing worlds remains entrenched. Beyond that, the rich world flirts with creating new border tariffs to punish those not taking equivalent action. Don’t accept this at face value – it is a neat excuse for the new post-pandemic protectionism.

The problem for Glasgow is the sheer chasm between the “now” and the future. Annual capital spending on new energy to meet demand and restructure to cut emissions must more than double. Yet the world is currently trapped in what The Economist calls “the first big energy scare of the green era”.

Britain is turning coal-fired power stations back on. Power shortages are plaguing China and India. On display are the problems inherent in any uneven transition to clean energy. Gas, oil and coal prices are soaring. The populist pot is being stirred against climate change policies at the exact moment those policies are supposed to be intensified at Glasgow.

Nothing, however, will stop the new energy economy emerging. It will be driven by costs, technology and the imperative for clean energy. Anybody thinking the current global price dislocations define the future is mistaken. In its 2021 report, the International Energy Agency said that, based on current policy settings, almost all net future growth in energy demand comes from low-emission sources.

The IEA outlook showed “fossil fuel demand slowing to a plateau in the 2030s and then falling slightly by 2050” – for the first time. Yet this would still see the global temperature climb 2.6C by 2100. It said that announced net-zero pledges by countries if implemented “in time and in full” – a heroic assumption – would “start to bend the global emissions curve down”. It was now apparent that solar PV or wind constitute “the cheapest available source of new electricity generation”.

In the US, Biden will have to manage the pro-coal Democrat from West Virginia, Joe Manchin, who has been blocking his principal energy measures.

In Australia, Morrison will have to manage his dilemmas as a compromise centrist with the progressives claiming his 2050/2030 targets are an untenable contradiction, and his right flank accusing him of betrayal and selling out over climate change.

Of course, this assumes a settlement will indeed be reached in the next couple of days with the Nationals. Everyone expects this, but the Nationals are capable of sudden surprises.

However, the moral seems apparent: no historic change on a matter of high policy is possible without provoking furious resentment. There are three highlights about Australia’s new position: it is a national interest imperative to achieve the 2050 benchmark; it reduces the Coalition/Labor climate change divide; and it creates a political time bomb on the populist right that will decide whether Morrison survives or falls.

The future is on display – ambitious assurances about a global clean-energy revolution in collision with entrenched and alarmed domestic politics. As the Glasgow conference looms, forget any notion that Australia is unique as the Coalition parties struggle to finalise their new stance.