Classroom classics revolution could save our failing society

Nothing is failing in Western societies more completely, and more tragically, than school education. We’ve sub-let our thinking out to algorithms, and in the process all but abolished deep learning, while embracing the terror of the screens. But there’s a way back.

We cram every ideological fad into the curriculum – safe schools, reconciliation, gender theory, race theory, decolonisation, peace studies, green worship, net zero hymns and devotions – yet division, alienation, even violence, spread.

Even as we’ve sometimes banned the use of mobile phones in school hours, we’ve flooded our schools with gadgets – laptops and iPads and endless, endless screens. But instead of producing citizens who master technology discerningly for their beneficial use, the memes and screens have fried our children’s brains, the relentless giddy, dizzy images, bright colours, dark colours, dopamine hits, changing images, fluid images, rapid image turnover, relentless distraction, have destroyed childhood, eaten adolescence and blighted young adulthood.

We’ve sub-let our thinking out to algorithms, and in the process all but abolished deep learning, while embracing the terror of the screens.

But there’s a way back.

Perhaps the most dramatic and hopeful development in all Western culture right now is the rapidly growing movement in the US, which is also gaining traction in Australia, for an approach of classical education in high schools. This is the same as what is often called the liberal arts approach.

It’s huge in the US, with 750-odd classical high schools and 100,000 students. Growing and growing.

It’s just getting started in Australia. I’ve been investigating this in recent months, on both coasts of the US and in three Australian states.

This is a road back to sanity, learning and truth in education. A road back to depth and texture in life. A road back to intellectual substance and enchantment.

If we’re lucky, these students will form eventually a leadership cadre in our culture.

What does classical education mean?

Mary Broadsmith, principal of Harkaway Hills College, a newish girls school in eastern Melbourne, which is not fully a classical school but has moved strongly in that direction, says: “We want students to pursue the good, the true and the beautiful.”

Frank Monagle, the founding principal last year of Sydney’s Hartford Academy (Ian Mejia is the principal this year), believes state education systems have a narrowly utilitarian ideology.

“The purpose of education was seen as getting a job,” he says.

“The true purpose of education is to help young people be the best young people they can be.”

Kenneth Crowther, the principal of the new St John Henry Newman School in Brisbane, which will take its first students in 2026, was a teacher for years before he embraced classical education.

“I realised there were deeper purposes around what it means to be a human being,” he says.

“We have this educational inheritance that we’ve rejected. I saw so much alienation. Fifteen-year-olds would say to me, ‘why am I studying Shakespeare, when will I use Shakespeare in a job?’

“This represented an ideology of utilitarianism, instead of seeing Shakespeare as a way to deeper meaning and purpose.”

Peter Crawford, academic dean of the US Institute of Catholic Liberal Education, whom I met in Napa, California, says: “The purpose of education is to teach children the art of being free.”

He adds: “A school first of all is a community.”

Claire Whereat, the secondary school head at Toowoomba Christian College, is another who, along with her school, which was established in 1979 and has 800 students, has been on a journey to a liberal arts approach. “We had to ask ourselves what is the purpose of education? The purpose of education is to form young people of wisdom,” she says. “A wise young person is able to engage in any topic with a critical understanding of truth, beauty and goodness. Wisdom is also for everyday life.”

All of these schools are classical, or liberal arts, schools up to a point. In Australia, every registered school, especially an independent school, needs to follow state and national curricula. But they can still organise much of their school’s effort around classical principles.

All these schools are explicitly Christian. In classical education, the idea of integrated understanding – as a Christian might say, all truth is God’s truth – is a central organising principle. An integrated understanding of the world leads to an integrated human being. But in the US many classical education schools, and many liberal arts colleges, are not religious. There are 50-odd Great Hearts Charter Schools, funded by government but with a local community given a charter of independence. They’re not religious but they still study the Great Books. This is not only for religious believers, though much of humanity’s greatest thinking focuses on God.

So what does classical education consist of at the practical level of teaching and content?

From speaking to dozens of teachers, principals, parents, students, movement leaders, education administrators and curriculum developers, I would offer the following summary.

Classical education offers the student an integrated understanding of life, culture, knowledge and the meaning of being a human being. It gives students direct exposure to what English poet Matthew Arnold called “the best that has been thought and said”, the greatest of the Great Books.

It promotes an intellectually sophisticated encounter with these writers through Socratic dialogues. It offers the thrill of chronological, deep history and the finest literature. As Crowther comments: “Contemporary education fails in giving students an understanding of how the (modern) world came about.”

Thus, a classical school student may study ancient Greek civilisation in history at the same time as reading ancient Greek plays in literature. If the school teaches philosophy and theology, as many do, that too will be co-ordinated.

Says Crowther: “The unity between subjects is very important in classical education. The modern system is very fragmented. The subjects don’t connect up.”

Socratic dialogue is critical. Students might have read Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, then explore in discussion the nature of evil. This inculcates moral education and accustoms students to disagreeing with each other, profoundly and passionately, but civilly, in friendship.

Many classical schools teach Latin, the most accessible of the classical languages, in which many of the greatest works, from ancient Rome through to the late Middle Ages, are written. Studying Latin helps students master English grammar, and understand the roots and history of words.

In the most junior years, children might begin their classical exposure through Aesop’s Fables or Arthurian legends. In Australian schools they’ll meet Snugglepot and Cuddlepie.

In the early years there’s an emphasis on play, but also on explicit instruction, led by the teacher, and on rote learning. Learning times tables and English grammar provides foundational knowledge, but also exercises brain muscle, memory, attention span.

In the US recently I journeyed out from Washington DC to Annapolis in Maryland, to spend an afternoon and evening with the Chesterton Academy of Annapolis.

I was met at a nearby rail station by Azin Cleary, who founded the school with her husband, Bill. She’s originally Iranian. The family left Iran when Azin was a teenager so her brother could avoid the army in the Iran/Iraq war. In the US she fell in love with Bill, a dashing air force pilot. He wasn’t very religious but told her he wanted to get married in a church, was pro-life, and wanted to bring his kids up Catholic.

Azin was fine with that. She was a disengaged Muslim and felt no pressure to change her religion. It was years later that she herself became Christian.

The classical education movement is extremely ecumenical. The Annapolis Chesterton Academy, although a school in the Catholic tradition, rents its space from a Lutheran church, to which it’s a close friend.

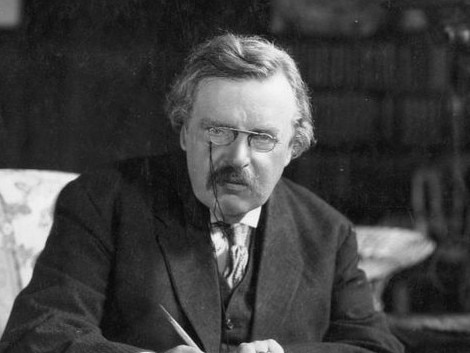

Two things are striking. First, it’s named after GK Chesterton, an English journalist – my hero – who died nearly a hundred years ago. Chesterton and CS Lewis, who died in the 1960s, are inspirations to the classical education movement. It reveres them, two of the most prodigiously gifted Christian writers of the 20th century, because they bring everything together. They wrote theology, biography, newspaper columns, novels, poetry, adventure stories, profound theological meditations. And they exuded joy.

The Chesterton schools movement has been going just 15 years but already has 62 high schools in the US and 10 overseas. Bill and Azin hadn’t heard of Chesterton when they were looking for something better for their kids. The Chesterton network provided them a full template for a classical school.

“It’s good to have someone tell you what to do when you don’t know what you’re doing,” Bill says modestly. Now they love Chesterton.

The school’s other striking feature is its no-gadgets policy. Students hand their phones in every morning. But also, throughout their entire school learning, they don’t use laptops, iPads or anything else. The fees are $US11,700 a year. That’s cheaper than many good Catholic schools, but the families typically have iPads and the like at home. The kids all have phones. They get computers. But school time is a screen-free oasis, a time for deep learning.

State school curriculum requirements are much less prescriptive than in Australia so classical schools can design the program they want. At the Chesterton Academy, the curriculum is full and demanding. For all four years of their senior secondary schooling, students study the humanities, maths and science, and the fine arts. In the humanities, they spend what Americans call Freshman Year in the ancient world. In literature: Homer, Aeschylus, Virgil and a book by Chesterton; in history: ancient Greece and Rome; in philosophy: Plato, Aristotle and formal logic; in theology: Old Testament. In Sophomore Year literature: Augustine, Chaucer, Shakespeare and Chesterton on St Francis and on Orthodoxy; history: early church and early medieval; philosophy: Plato and Aristotle; theology: New Testament. In Junior Year literature: Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, plus Chesterton on Thomas Aquinas; history: Renaissance, Reformation, and Counter-Reformation; philosophy: Aquinas, Descartes, Hobbes; theology: the Catholic Catechism. And in senior year literature: Goethe, Dickens, Dostoevsky, Orwell, plus Chesterton’s classic, The Everlasting Man; history: American and French Revolutions, US Civil War, World Wars I and II, communist revolutions; philosophy: Locke, Rousseau, US Founding Fathers, Marx and more Chesterton.

In all four years, students study Latin and practise debate, take maths and science, practise and study art (really the history of art), practise and study music, and stage plays, including in senior year a full-length Shakespeare. And of course they play sport.

That is a rich and taxing educational experience. Not every student could manage it, not every school could attempt it. Notice there are no elective choices for students? This is extremely sensible.

When I was at secondary school, English, maths, science and history were compulsory. We could choose an elective combination either of Latin and French, or commerce and geography. I’m profoundly grateful I studied Latin and French and didn’t have elective choices, at age 14, like guitar, environment studies, or, as in some American schools, “forensics”, in which kids actually get to waste their time watching NCIS episodes and pretend it’s school work.

No electives and no gadgets at all, and the students graduating from Chesterton Academy are blitzing college entrance exams and pursuing stellar academic and professional careers. If you can think well and hard, and read deeply, you can master anything.

Some US states actively promote classical education. Florida recognises the Classical Learning Test as the equivalent to the SAT for college admission.

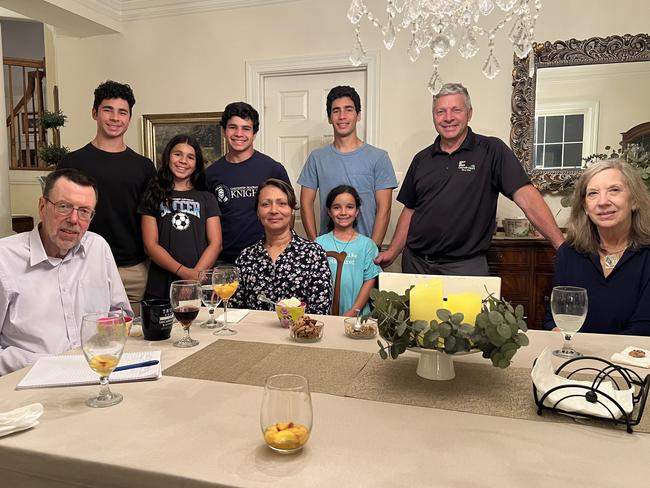

That night I had dinner with Bill and Azin, five of their six kids, Azin’s mum, and a school board member, at the Clearys’ home. They may be the nicest people I’ve ever met. The kids are years ahead of their respective age groups in conversation and sophistication. Nor do they automatically agree with each other, with me, or with their parents. But also, they actually seem to like their parents, and even to find the conversation of a visiting journalist from Australia worth turning up for. The oldest son, Matthew, a college student, after dinner drives me all the way back to Washington and is an absorbing conversationalist.

Kids at this Chesterton Academy are lucky. But classical, or liberal arts, education is a broad movement. There are lots of different shades of emphasis, different intensities. Australian liberal arts schools also de-emphasise gadgets. But because NAPLAN assessments have foolishly gone online, no school now can banish gadgets altogether. Some classical schools have classes on gadgets to acquire particular skills, typing or coding, but don’t use them in most classes.

Whereat tells me the science is conclusive. When students take notes by hand they can’t write as quickly as when they type, so they actually have to process and select information much more actively. They learn better taking notes by hand than typing notes on an iPad.

Broadsmith comments: “One of the problems we have is not that students aren’t interested (in deep learning) but they’ve been taught that everything has to be fast and snappy.” Students see devices not as paths to contemplation but as sources of entertainment and distraction. Efforts to ban social media for kids are a tiny recognition that gadgets fry brains.

No Australian school could produce a curriculum like the Chesterton Academy because of the state requirements, which are obviously necessary for accountability but seem to emphasise mediocrity, ideology, narrowness in the faux service of choice, triviality, incoherence.

Claire Whereat tells Inquirer that the Toowoomba Christian College secondary literature curriculum includes Shakespeare, Dickens, Jane Austen, Louisa May Alcott, Pilgrim’s Progress, To Kill a Mocking Bird. They’re all good choices.

She also makes a profound point about teaching history chronologically: “You can’t understand where Australia has come from if you don’t understand the Judeo-Christian background, or the Westminster system.”

All the classical or liberal arts schools teach grammar. She says: “We spend a lot of time looking at beautiful words, looking closely at what words mean, their Latin and Greek roots.”

NSW schools enjoy one happy curriculum freedom because of the legacy of former premier Bob Carr. Monagle says: “Carr saved history as a discipline.”

In other states history has been rolled into geography and social studies and mangled into a thousand incoherent pieces, often at best a few isolated case studies and relentless agitprop.

Carr recalls: “I insisted on maintaining the traditional disciplines. I wanted curriculum rigour. I insisted history remain a separate subject. History could be defined as what happened next and why. I also reinstated traditional grammar, and corrected the retirement of Shakespeare from English courses.”

Carr wrote his own version of a guide to the Great Books in his much-neglected My Reading Life, which is a classic of sorts in Australian letters. He thinks now a suitably supple Great Books approach has a lot to recommend it.

Dedicated classical and liberal arts schools are just beginning in Australia. But existing schools, especially Catholic and Christian schools, are increasingly examining this option. It’s a trend. It’s the future.

In an important recent speech, Sydney Catholic Archbishop Anthony Fisher argued for a move to a more integrated liberal arts approach in Catholic schools. He asked: “How might we cultivate a more expansive educational environment, whereby all academic disciplines interconnect and serve the transmission of faith and development of the whole child?”

In a distressed and bleeding culture, these schools are field hospitals; perhaps more than that – base camps; perhaps more than that – signs of a new creation.

Nothing is failing in Western societies more completely, and more tragically, than school education. This is especially so in Australia. Billions upon billions of new dollars – Gonski funding, NAPLAN funding, state promises, federal commitments – and yet the results, even measured in narrow, utilitarian, technical terms, get ever worse and we sink further down the international education league tables.