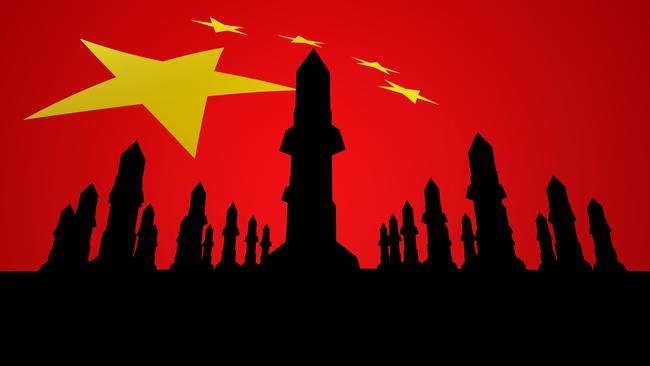

China’s ballistic missile program a wake-up call to the nation

China’s PLA is the world leader in developing anti-ship ballistic missiles. Trying to change Beijing’s calculus should be a high priority in Canberra.

In the years since, PLA programs have only accelerated: China now has hypersonic missiles (which travel five to 10 times the speed of sound, making them extraordinarily hard to intercept) and hypersonic glide vehicles (space shuttle-like warheads accelerated to hypersonic speed by a ballistic missile, which can orbit the planet and re-enter the atmosphere to strike a target anywhere on Earth). The PLA is building missile launch complexes – hectare upon hectare of subterranean silos – in China’s western desert, and constructing replicas of US ships as mobile targets.

As the name suggests, anti-ship ballistic missiles are designed to destroy surface warships, though they can also target fixed locations, such as ports, air bases and, under certain circumstances, submarines. Chinese systems are land-based and road-mobile. Like other ballistic missiles, ASBMs follow a parabolic path, passing briefly through space before descending to their targets. In 2020 China claimed its ASBMs – the most advanced on the planet – had demonstrated the ability to manoeuvre during descent (avoiding missile defences) and then strike a moving target at sea.

China’s two principal ASBMs are the DF-26, with a range of at least 4000km, and the DF-21D, which can strike targets at 1685km. Even with non-nuclear payloads, ASBMs are sufficient to sink major fleet units, including big-deck amphibious ships (such as HMAS Canberra or Adelaide) or aircraft carriers, hence their nickname, “carrier-killers”.

ASBMs matter because of their potential placement in our region.

When China’s security agreement with Solomon Islands was revealed in April last year, it prompted much discussion about spheres of influence, introspection about Australia’s colonial legacy in the Pacific and debate about China’s ambitions in the region. In July, under pressure from Australia and others, Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare ruled out a permanent Chinese military base in the country. The cancellation of a Chinese company’s attempt to lease the island of Tulagi, whose harbour makes it an attractive naval base, reduced tension, but a different Chinese company is still pursuing plans to purchase an airstrip and deep-water port at Kolombangara, in the New Georgia group of the northwest Solomons. Chinese advisers have deployed to train Solomon Islands security forces, and the emergence of the Southwest Pacific as a zone of great-power competition remains of concern in Canberra.

China’s ties with Solomon Islands – and other Pacific states – must be understood through the lens of the PLA’s long-range missile capability. To be clear, there is currently no public evidence that Beijing intends to place ASBMs at any of China’s offshore bases or in Chinese-controlled ports across the Indo-Pacific, let alone in the Solomons. But from a military standpoint, strategists understand future threats by analysing capability (which takes years to build) rather than intent (which can change in an instant).

Consider the precedent of the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. In March 2015, foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying insisted Beijing’s intentions in the islands were peaceful, seeking merely to fulfil China’s international obligations in areas such as maritime search and rescue. Six months later, during a press conference with Barack Obama, Xi Jinping acknowledged that the PLA was building runways and living facilities in the Spratlys but claimed “China does not intend to pursue militarisation”.

These soothing statements were abruptly walked back in 2016 after the discovery of radars and missile emplacements on the islands. By 2018, the PLA had stationed surface-to-air missiles in the Spratlys, along with cruise missiles able to strike ships 545km away, and was staging nuclear-capable H-6 strategic bombers through the islands. Chinese intentions, in other words, were peaceful – until they weren’t.

Beijing’s record of deception and obfuscation in the Spratlys (and elsewhere) suggests capability, rather than stated intent, must guide any threat assessment, especially when it comes to long-range strike assets such as ASBMs. Maps showing the ranges of PLA missiles often portray them as if measured from the outermost edge of mainland Chinese territory; on such maps, the DF-21D’s range appears to extend to northeastern Borneo, while the DF-26 reaches northwestern Papua New Guinea and falls just short of Darwin.

This is unrealistic, of course: the PLA does not deploy missile units right on China’s borders. A more accurate depiction (based on the location of the PLA Rocket Force’s first DF-26 unit, thought to be based in Henan Province) gives a range that reaches Borneo and brushes the Vogelkop on the northwestern tip of Indonesia’s Irian Jaya province.

But ASBMs are not constrained to mainland China. Both launchers and missiles can be shipped in the vehicle deck of a car ferry or amphibious ship. Transported by sea, they could be placed on any Chinese-controlled island or at any of the ports and naval bases China owns or is building across the Indo-Pacific.

These include the harbour at Hambantota in Sri Lanka, the naval base under construction at Ream in Cambodia, the port of Gwadar in Pakistan and Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, all of which are Chinese-controlled, while two (Djibouti and Ream) are PLA bases or shared facilities.

Obviously enough, a Chinese base in Solomon Islands could serve the same purpose. Forward positioning could occur openly, or covertly with support from “denial and deception” activities, as during the Soviet deployment of medium-range nuclear missiles by cargo ship to Cuba in 1962.

The PLA has the ability to ship missiles to any Chinese-controlled port facility, then operate them from container-based launchers or from a truck-like system (called a transporter-erector-launcher), with or without the knowledge of the government concerned. A pre-developed pattern of “lily pads” – a network of regional sites set up to receive missiles and launchers when needed – would enable rapid deployment of ASBMs in a crisis or conflict.

If Solomon Islands became part of a Chinese lily-pad network, the implications would be profound. DF-26s in the Solomons could strike ships anywhere west of Fiji or Tuvalu, south of the Marshall Islands, north of Brisbane, or east of Wewak, in PNG. They could prevent ships leaving Cairns, Townsville and Brisbane, block transit through the Torres Strait, interdict export terminals in Queensland and NSW, and deny movement around Vanuatu, Nauru and New Caledonia. Shipping routes connecting Australia and New Zealand with Asia and the US – which pass through the Solomon Sea, between New Ireland and Bougainville, carrying much of our maritime trade – would be threatened. Australia’s energy imports, critical to every aspect of national life, would be severely impacted, while our ability to protect fibre-optic cables and other offshore infrastructure would be hampered, since naval forces would need to avoid the PLA’s missile bubble.

Such a “sea denial” strategy, employing a web of land-based ASBMs overlaid with cruise missiles, bombers, submarines and surface warships, is exactly the approach China is taking in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait. Described recently as an “anti-Navy”, it has changed Washington’s entire risk calculus for deploying naval forces into the region. Naval commanders are now much more cautious about risking fleet units in the area, while analysts, for the first time this year, assessed the US military’s ability to perform assigned tasks in the Western Pacific as “weak”.

If China applied the same approach off Australia’s northeast coast, this would severely limit Washington’s appetite to assist us in a crisis. In extremis, it could block American or allied reinforcements in a major war, leaving Australia isolated unless we develop the capacity to neutralise it – or, far better, prevent the PLA from putting it into practice.

The impact of even potential placement of ASBMs would be almost as significant as their actual deployment. Merely by creating a sustained presence in the Solomons (say, under the guise of ongoing security assistance) and then resupplying deployed troops with vessels capable of carrying containerised missiles, China would send an important message. The PLA would, in effect, be demonstrating the capacity to interdict maritime movement across an enormous area, excluding American and Australian naval forces from Southwest Pacific. Communicating that capability would allow Beijing to call the shots across the region in political, economic and diplomatic terms. All this suggests that changing China’s calculus should be a high priority in Canberra.

At the strategic level, the tactical and operational implications of Chinese ASBMs are concerning. As far as China is concerned, American strategic ambiguity on Taiwan increasingly looks as if it masks uncertainty, while economic sanctions and technology restrictions (particularly on semiconductors and critical commodities) risk backing Beijing into a corner. US Navy commanders openly talk of a danger window, starting this year and running until 2027, when China will be in the strongest position it will ever reach, relative to the US, and may be tempted to move against Taiwan – an action that would almost certainly provoke a wider war in the Pacific, drawing Australia in.

Australian leaders of all parties would do well to consider the risks involved in continuing to tie Australia so tightly to an alliance partner that is clearly in relative, if not absolute, decline. This does not imply walking away from ANZUS, let alone attempting to play both sides or position ourselves as neutral in a future conflict. After everything that has happened in our relationship with China, this would be unlikely to work, while telegraphing weakness that might only provoke an attack. Rather than rejecting the US alliance, Australian strategists should be realistic about its limits.

In a crisis over Taiwan, it is entirely possible that Washington might back down from a confrontation. Even if the US were to fight China and win, Australia would likely suffer heavily. And if US forces fought and were defeated, the impact would be even worse.

In any of these cases, Chinese ASBMs in Southwest Pacific – cutting us off from reinforcement and resupply, blockading critical commodities, interdicting our seaborne trade – would pose an existential threat. In May 1942 the US Navy, along with Australian warships and land-based aircraft operating from Townsville, defeated a Japanese invasion fleet in the Battle of the Coral Sea, buying time for Australia to mobilise against the Japanese onslaught and allowing the US to deploy forces to Australia and, in time, mount a counterthrust.

In a future Pacific war, such a battle might never take place if ASBMs had already been pre-positioned in the region. Any battle would involve heavy losses with limited chance of success: US commanders might refuse to risk scarce, critical national assets such as aircraft carriers under those conditions. Even if the US were only temporarily neutralised in the initial phase of a conflict with China, a PLA missile bubble in the Southwest Pacific would mean Australia might need to survive unaided for a considerable time, perhaps years. This perhaps sounds alarmist, but unless Australians understand the stakes, we run the risk of missing the urgency of the problem. Prevention is critical: retaking a regional lily pad, once ASBMs were established, would require the entire ADF and, even with US help, we would likely suffer casualties on a scale unprecedented since 1945.

Nor can we rely on Washington to rescue us – whether American leaders want to help or not, their capacity to do so is clearly declining. Instead, we need to engage partners, now, to develop regional deterrence and a cost-imposition strategy. This alone would not solve the problem but it might buy time for urgently needed military modernisation (including theatre missile defences, our own long-range strike assets, the ability to project joint forces into the region and a capability for stealthy distributed operations).

It would also buy time to improve national resilience across the board, an effort that is crucial given the sharply increasing likelihood of conflict between our most important trading partner and our traditional military and political ally. Seen in this light, China’s pact with Solomon Islands is not simply a matter of economic and political influence but also a matter of firepower, missile ranges and hard-power logic. Given the risks involved, it ought to be a wake-up call for Australia.

This is an edited extract from David Kilcullen’s article Wake-Up Call in Australian Foreign Affairs. Out Monday.

Anti-ship ballistic missiles are a class of medium or intermediate-range ballistic missiles pioneered by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, the world leader in developing them. A US intelligence assessment in 2017 noted: “China continues to have the most active and diverse ballistic missile development program in the world. It is developing and testing offensive missiles, forming additional missile units, qualitatively upgrading missile systems, and developing methods to counter ballistic missile defences.”