China climate and subs deals loom as traps for Australia

We should take notice of the surprise US-China joint pledge on climate. Where is Australia? Nowhere.

And where is Australia?

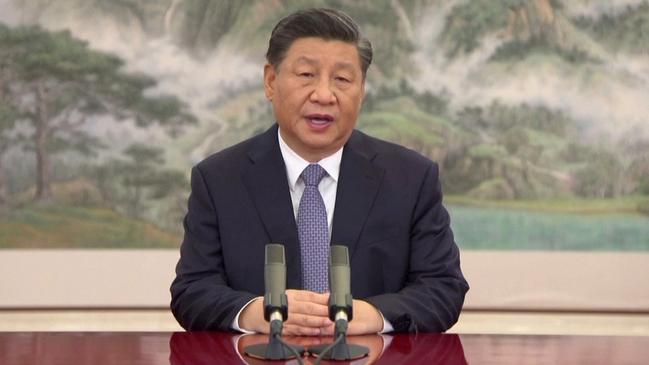

Nowhere. The prospect now is for deeper US-China dialogue amid their flawed, competitive relations. But the expected Xi-Biden virtual meeting only highlights Australia’s dilemma.

Our ministers have no communications with China – no phone calls, no letters, no meetings, and no visits.

Biden can meet with Xi but Scott Morrison cannot. Biden’s America can do deals, but Morrison’s Australia cannot. And what future deals might the US do with China that don’t align with Australia’s interest?

As a postscript, how Xi must chuckle as he talks with America but keeps Australia in the deep freeze.

The longer this status quo prevails, the deeper the embarrassment and dilemma for Australia since no access to the most powerful nation in East Asia is a problem that can only become a permanent negative for Australia.

Australia is being taught a lesson in great power relations. China needs to communicate and sit down with the US. It doesn’t need to do this with Australia because the price it pays is not sufficiently harmful. China got Australia wrong by thinking it would fold under economic coercion. But neither Beijing nor Canberra is willing to make the political concessions required to re-establish communications, so the stalemate continues.

After a strained opening year of Xi-Biden relations, the two leaders have sent letters creating a positive tone for their expected November 15 meeting. Xi’s letter said China is willing to “enhance exchanges and co-operation across the board … so as to bring China-US relations back to the right track”.

The meeting is virtual because Xi won’t leave China. Biden would prefer a face-to-face encounter. Neither side is likely to make concessions but the atmospherics should improve. The climate announcement, weak on specifics, took a year for Biden’s envoy John Kerry to negotiate in dozens of meetings with Chinese officials.

Xi and Biden have got a vested interest in singing from the same song sheet: no cold war in the Asia-Pacific. In case you missed the point, Biden’s National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, speaking to an Australian audience this week, repeated Biden’s position: “We are not seeking a new cold war, we’re not looking for conflict, what we’re looking for is effective competition with guardrails and risk-reduction measures in place to ensure things don’t veer into conflict.”

Sullivan said Biden’s purpose was “to work together with China where it’s in the common interests of our countries and in the interests of the world to do so”. He said all the talk about the US and China going into conflict or the Thucydides Trap overlooked the point: “We have the choice not to do that.”

The issue is whether the “no cold war” mantras merely disguise the march towards deeper conflicting interests or actually point to management of a great power rivalry.

Delivering the 2021 annual Lowy Lecture in a virtual address, Sullivan sketched out the guiding principles that govern Biden’s approach to the world. The first priority is replenishing and restoring America at home – reinvestment in infrastructure, human capital, innovation and “the basic building blocks of our economy and our society”. Hence the huge spending bills Biden is pushing through congress.

Biden believes foreign and domestic policy must operate in lock-step. His political ambition is to restore the American middle class; his policy ambition is to renew the engine of American dynamism, from manufacturing to hi-tech, to meet the China challenge.

Conflict with China doesn’t appear in Biden’s script. Biden wants to strengthen America, to muscle up safely against China but avoid any cold war – a difficult task with its viability depending on Xi, whose leadership and grip on power is being extended at the precise time Biden’s leadership constituency is weakening.

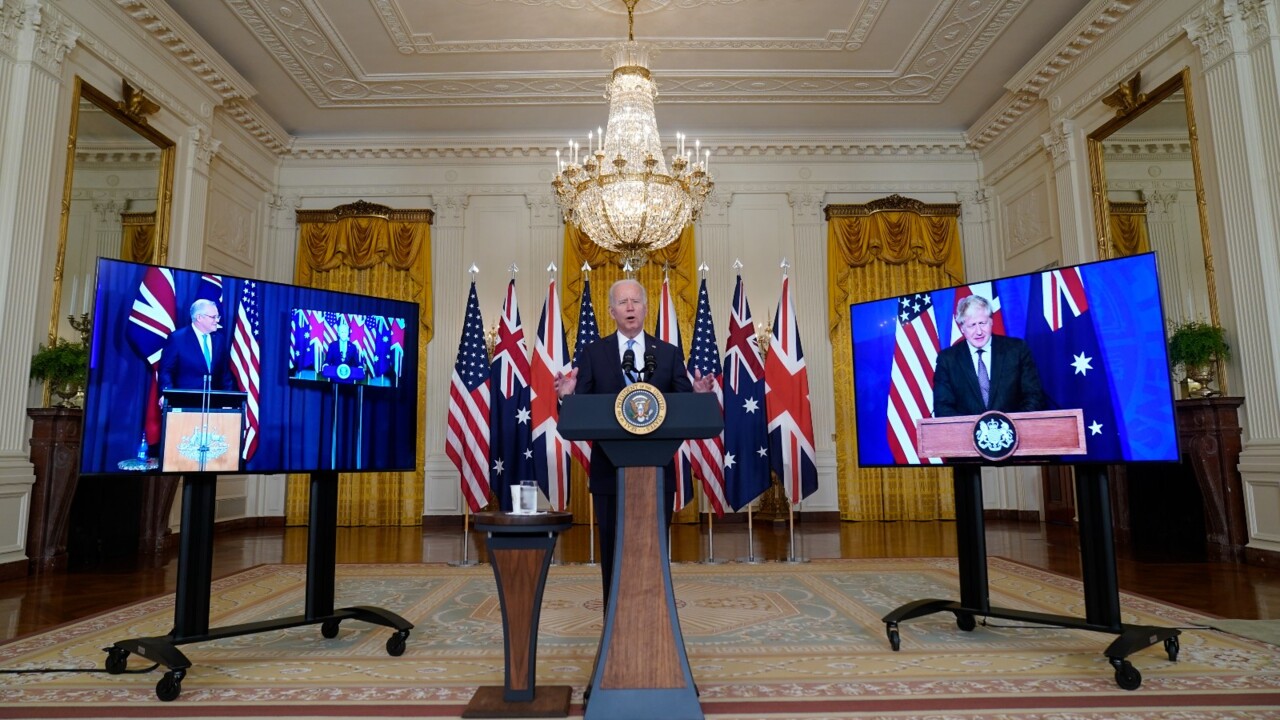

Biden’s second priority is rebuilding old alliances and creating new partnerships, with Sullivan nominating as the top examples the Quad summit involving the US, Australia, Japan and India and the AUKUS nuclear submarine agreement constituting the US, UK and Australia. These priorities are good news for Australia.

Sullivan said Biden wanted to send a message to Australia and the world: “If you are a strong friend and ally and partner and you bet with us, we will bet with you.” This is how Biden promotes his diplomacy. But the stakes here could hardly be higher for Australian-US relations. The US has made a commitment, and what counts now is its delivery to Australia.

Sullivan said Biden wants to “turn the page on an overemphasis on military engagement and war and an under-emphasis on diplomacy in key parts of the world” – notably the broader Middle East region. Biden sees himself as restoring the US diplomatic leadership that Donald Trump sabotaged. That judgment is correct but it begs the related question: does Biden possess the toughness to manage Xi? Doubts on that score can hardly be overlooked.

As Australia deepens its strategic alliance with the US, it needs to get the contours right. America will play its leadership role in sorting where to confront and co-operate with China – but Australia occupies a different boat. For Australia, it is a mistake to think that deepening the US alliance is a substitute for our collapsed relations with China. That doesn’t work.

As the Glasgow meeting wraps up, the joint announcement from John Kerry and China’s climate envoy Xie Zhenhua reveals everything you need to know – this is gesture politics and climate action fused in inseparable orchestration.

China, as the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, knows it must present as a responsible global citizen on climate yet it will keep running energy policy in its own self-interest. Biden has no time for Australia’s political problems over fossil fuels. The US-China statement merely confirms that Morrison will remain under permanent pressure to provide more ambitious medium-term targets and that his net-zero at 2050 stance was vital for Australia to skate through the Glasgow meeting.

In his speech, Sullivan offered a reassurance of sorts for Australia – after the global diplomatic assault from French President Emmanuel Macron and criticism of Australia by Biden, the US remains pledged to the AUKUS agreement for the long-term. Sullivan said America would back Australia “with the most advanced, most sensitive technology we have” because “we trust you, we believe in you”.

“Good allies to the United States deserve a good ally in the United States back to them,” Sullivan said. “And that’s what led to the United States in 1958 providing this nuclear propulsion technology by Eisenhower to (then British PM Harold) Macmillan. And it’s what led Joe Biden to step forward to say he wants to travel this road with Australia. And it’s a road we will travel together, literally, for decades to come.”

There could be no stronger or long-term pledge. AUKUS puts strategic intimacy onto another plateau that must last for most of the coming century. Opening the door for Australia to develop a nuclear submarine fleet is unprecedented in technological support and alliance ambition. Have no doubt, it will test the alliance and test the trilateral UK-US-Australia collaboration as never before. Sullivan, in response to questions from Lowy Institute executive director Michael Fullilove, admitted there had been “some challenges” dealing with the AUKUS rollout and engagement with the French. That’s a polite way of describing Biden’s horror at upsetting the French and his subsequent appeasement of Macron.

Sullivan implied that chapter was terminated and the task now was to “look at actually putting this thing into place”.

Australian sources confirmed on Friday that the Morrison government in the near future would provide more details on the meaning, direction and implementation of AUKUS with an 18-month or shorter period designated to finalising decisions on the type of boat. Given the political dramas since the September 16 announcement, this is imperative.

A trilateral agreement has advantages and disadvantages. This deal originated with Morrison and Boris Johnson – the US was only brought in after the UK-Australia partnership was sorted.

You can be sure that Johnson will be looked after in the final decisions. But this must be balanced against the reality that the US is the world leading exponent in nuclear submarine technology, and securing access to its “crown jewels” is central to Australia’s goals.

How will the competition be resolved between the UK and the US in chasing their respective benefits from the proposed Australian nuclear submarine fleet, with the ultimate question being does Australia go with either the UK or US boat?

Central to any arrangement must be Australian access to, and crewing with, either UK or US nuclear subs. This needs to begin as soon as possible, along with getting Australian engineers involved. Hosting British submarines in Australian facilities could allow the Australian Navy to begin to get the crewing experience that will be essential.

The US has told Australia the level of “nuclear stewardship” will be a non-negotiable requirement. The US could not afford an accident in the Australian nuclear program. When AUKUS was announced, a Biden administration official said: “I do want to underscore that it’s very hard to over-estimate how challenging and how important this endeavour will be. Australia does not have a domestic nuclear infrastructure. They have made a major commitment to go in this direction. This will be a sustained effort over years.”

The assurances provided by Sullivan this week were valuable but left unanswered the pivotal question: what exactly is the US committed to under AUKUS? The September statement by the leaders – Morrison, Johnson and Biden – was lofty but vague. They pledged to “commit to a shared ambition to support Australia in acquiring nuclear-powered submarines” and “leverage expertise” from the US and UK, with the submarines being “a joint endeavour between the three nations”.

The obligations of the UK and US under the agreement need to be clarified. The same applies to the construction agenda, which is complicated by domestic politics. At some point, presumably after the South Australian election in March and the federal election, probably in May next year, the government must modify or abandon its initial claim that the submarines, from the start, will be built in Adelaide. That is not tenable, a point widely recognised. “There will be a lot of bump and grind in the US system as we sort this,” an Australian official said.

The related assurance offered by Sullivan came in response to a question put by Frank Lowy as conveyed by Fullilove: how did he respond to Australian critics saying the US was not a resident power in Asia, unlike China, and hence it would not possess “the staying power”.

This promoted the firmest reply of the evening. “First of all, we are a resident power in the Indo-Pacific,” Sullivan said. “We are resident with substantial long-term troop presence in Japan, in Korea, in Australia. We have just this year renewed the visiting forces agreement with the Philippines. At any given moment, American surface and undersea assets are at work, enforcing freedom of navigation, engaging in exercises, engaging in work on humanitarian assistance and disaster response.

“And so we have been a resident power in the Indo-Pacific for decades. It is fundamental to our identity. And President Biden has been very clear with our allies – as with our competitors – that the United States is a Pacific nation, has been a Pacific nation and will always be a Pacific nation. The fact that we are only doubling down on that – with what AUKUS represents and offers – shows that the direction arrow is pointing in terms of more intensive engagement, not less.”

Sullivan is right on the history. He is also likely to be right about the future. People who think the US will fade away or retreat from the Pacific don’t get either its history or its compelling national interests in the Indo-Pacific.

Australia should take notice of the surprise US-China joint announcement on climate change. Whether tokenism or substantial, it sends a message that Beijing and Washington are talking, negotiating and engaging at the highest levels, with a virtual meeting coming up between the presidents Xi Jinping and Joe Biden.