China and the US can exist in a positive rivalry

The deeply conflicting nature of US and Chinese strategic objectives and the profoundly competitive nature of the relationship may make conflict, and even war, seem inevitable — even if neither country wants that outcome. China will seek to achieve global economic dominance and regional military superiority over the US without provoking direct conflict with Washington and its allies. Once it achieves superiority, China will then incrementally change its behaviour toward other states, especially when their policies conflict with China’s ever-changing definition of its core national interests. On top of this, China has already sought to gradually make the multilateral system more obliging of its national interests and values.

But a gradual, peaceful transition to an international order that accommodates Chinese leadership now seems far less likely to occur than it did just a few years ago. For all the eccentricities and flaws of the Trump administration, its decision to declare China a strategic competitor, formally end the doctrine of strategic engagement and launch a trade war with Beijing succeeded in making clear that Washington was willing to put up a significant fight. And the Biden administration’s plan to rebuild the fundamentals of national US power at home, rebuild US alliances abroad and reject a simplistic return to earlier forms of strategic engagement with China signals that the contest will continue, albeit tempered by co-operation in a number of defined areas.

The question for both Washington and Beijing, then, is whether they can conduct this high level of strategic competition within agreed-on parameters that would reduce the risk of a crisis, conflict and war. In theory, this is possible; in practice, however, the near complete erosion of trust between the two has radically increased the degree of difficulty. Indeed, many in the US national security community believe the CCP has never had any compunction about lying or hiding its true intentions in order to deceive its adversaries.

In this view, Chinese diplomacy aims to tie opponents’ hands and buy time for Beijing’s military, security, and intelligence machinery to achieve superiority and establish new facts on the ground.

To win broad support from US foreign policy elites, therefore, any concept of managed strategic competition will need to include a stipulation by both parties to base any new rules of the road on a reciprocal practice of “trust but verify”. The idea of managed strategic competition is anchored in a deeply realist view of the global order. It accepts that states will continue to seek security by building a balance of power in their favour, while recognising that in doing so they are likely to create security dilemmas for other states whose fundamental interests may be disadvantaged by their actions.

The trick in this case is to reduce the risk to both sides as the competition between them unfolds by jointly crafting a limited number of rules of the road that will help prevent war. The rules will enable each side to compete vigorously across all policy and regional domains. But if either side breaches the rules, then all bets are off, and it’s back to all the hazardous uncertainties of the law of the jungle.

The first step to building such a framework would be to identify a few immediate steps that each side must take in order for a substantive dialogue to proceed and a limited number of hard limits that both sides (and US allies) must respect. Both sides must abstain, for example, from cyber attacks targeting critical infrastructure.

Washington must return to strictly adhering to the “one China” policy, especially by ending the Trump administration’s provocative and unnecessary high-level visits to Taipei. For its part, Beijing must dial back its recent pattern of provocative military exercises, deployments and manoeuvres in the Taiwan Strait. In the South China Sea, Beijing must not reclaim or militarise any more islands and must commit to respecting freedom of navigation and aircraft movement without challenge; the US and its allies could then (and only then) reduce the number of operations they carry out in the sea. Similarly, China and Japan could cut back their military deployments in the East China Sea by mutual agreement over time. If both sides could agree on those stipulations, each would have to accept that the other will still try to maximise its advantages while stopping short of breaching the limits.

Washington and Beijing would continue to compete for strategic and economic influence across the various regions of the world. They would keep seeking reciprocal access to each other’s markets and would still take retaliatory measures when such access was denied. They would still compete in foreign investment markets, technology markets, capital markets, and currency markets. And they would likely carry out a global contest for hearts and minds, with Washington stressing the importance of democracy, open economies and human rights, and Beijing highlighting its approach to authoritarian capitalism and what it calls “the China development model”.

Even amid escalating competition, however, there will be some room for co-operation in a number of critical areas. This occurred even between the US and the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. It should certainly be possible now between the US and China, when the stakes are not nearly as high.

Aside from collaborating on climate change, the two countries could conduct bilateral nuclear arms control negotiations, including on mutual ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, and work towards an agreement on acceptable military applications of artificial intelligence. They could co-operate on North Korean nuclear disarmament and on preventing Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. They could undertake a series of confidence-building measures across the Indo-Pacific region, such as co-ordinated disaster-response and humanitarian missions. They could work together to improve global financial stability, especially by agreeing to reschedule the debts of developing countries hit hard by the pandemic. And they could jointly build a better system for distributing COVID-19 vaccines in the developing world.

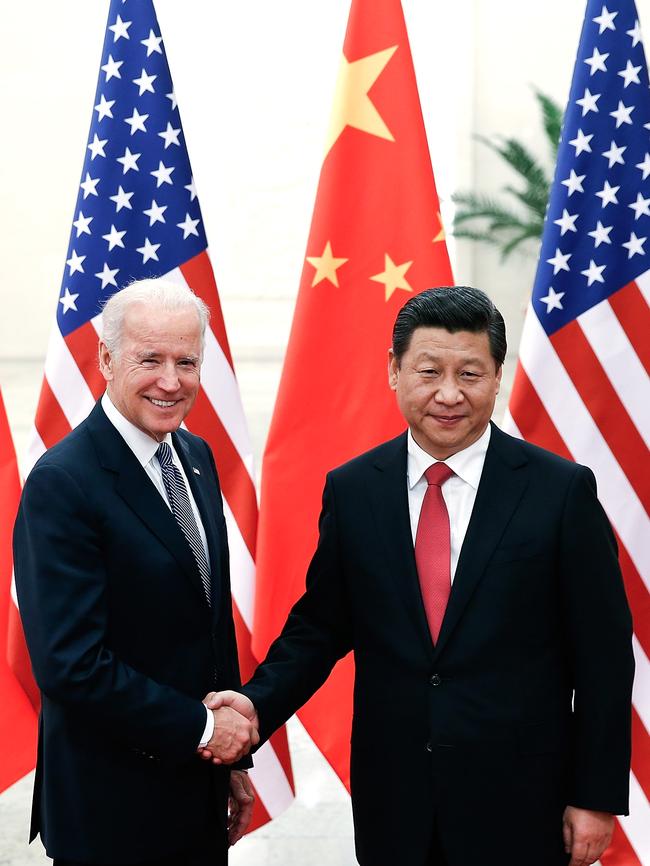

That list is far from exhaustive. But the strategic rationale for all the items is the same: it is better for both countries to operate within a joint framework of managed competition than to have no rules at all. The framework would need to be negotiated between a designated and trusted high-level representative of Joe Biden and a Chinese counterpart close to Xi Jinping; only a direct, high-level channel of that sort could lead to confidential understandings on the hard limits to be respected by both sides.

The two people would also become the points of contact when violations occurred, as they are bound to from time to time, and the ones to police the consequences of any such violations. Over time, a minimum level of strategic trust might emerge. And maybe both sides would also discover the benefits of continued collaboration on common planetary challenges, such as climate change, might begin to affect the other, more competitive and even conflictual areas of the relationship.

There will be many who will criticise this approach as naive. Their responsibility, however, is to come up with something better. Both the US and China are currently in search of a formula to manage their relationship for the dangerous decade ahead. The hard truth is that no relationship can ever be managed unless there is a basic agreement between the parties on the terms of that management.

Game on

What would be the measures of success should the US and China agree on such a joint strategic framework? One sign of success would be if by 2030 they have avoided a military crisis or conflict across the Taiwan Strait or a debilitating cyber attack. A convention banning various forms of robotic warfare would be a clear victory, as would the US and China acting immediately together, and with the World Health Organisation, to combat the next pandemic. Perhaps the most important sign of success, however, would be a situation in which both countries competed in an open and vigorous campaign for global support for the ideas, values and problem-solving approaches their respective systems offer — with the outcome still to be determined.

Success, of course, has a thousand fathers, but failure is an orphan. But the most demonstrable example of a failed approach to managed strategic competition would be over Taiwan. If Xi were to calculate that he could call Washington’s bluff by unilaterally breaking out of whatever agreement had been privately reached with Washington, the world would find itself in a world of pain.

In one fell swoop, such a crisis would rewrite the future of the global order.

A few days before Biden’s inauguration, Chen Yixin, the secretary-general of the CCP’s Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, stated “the rise of the East and the decline of the West has become [a global] trend and changes of the international landscape are in our favour”. Chen is a close confidant of Xi and a central figure in China’s normally cautious national security apparatus, and so the hubris in his statement is notable. In reality, there is a long way to go in this race. China has multiple domestic vulnerabilities that are rarely noted in the media. The US, on the other hand, always has its weaknesses on full public display — but has repeatedly demonstrated its capacity for reinvention and restoration.

Managed strategic competition would highlight the strengths and test the weaknesses of both great powers — and may the best system win.

Kevin Rudd is a former prime minister of Australia. This is an edited extract from his essay, Short of War, in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs.

Officials in Washington and Beijing don’t agree on much these days, other than that the contest between their two countries will enter a decisive phase in the 2020s.