Childcare shortage: Who’s minding the baby?

Parents returning to the workplace have trouble finding affordable childcare as staff leave the sector.

New mum Haley Devereux is growing nervous as she starts hunting for daycare so she can head back to work next year.

With baby Jac’s grandparents living in England, the Melbourne IT marketing professional is counting on quality childcare to continue her career.

“There are very long wait lists,” Devereux says.

“I know of mums who were looking while they were pregnant, and putting names down before their baby was born – it’s crazy.”

As Australia’s economy whimpers back to life after lockdowns and workers flock back to the office, many families are facing problems finding affordable and reliable childcare.

Daycare operators are facing unprecedented staff shortages as exhausted and low-paid educators are lured to work in other industries – or even to early retirement.

Already, one in eight daycare centres is operating without the required number of teachers and carers, as staff shortages force the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority to exempt centres from legislated staffing ratios.

Vaccination mandates are a flashpoint for a sector weakened after nearly two years of Covid-19 chaos.

“Mandatory vaccinations are hitting across the country – we’ve just lost 10 per cent of our workforce who won’t get vaccinated,” Australian Childcare Alliance vice-president Nesha Hutchinson says.

“There’s a level of anxiety every day in childcare centres – every time someone coughs, we have to ask is this a Covid issue? Has everyone been tested? Our workforce is exhausted and stressed and leaving or retiring early, and we can’t replace them.”

With pay rates scraping the minimum wage, childcare staff are leaving to work in the retail or hospitality industries, or switching to centres that can afford to poach them with higher pay.

The award wage starts at $20.80 an hour, or $40,095 a year, rising to $56 an hour, or $74,662 a year for a centre director with six years’ experience – still well below the average Australian wage of $90,000.

Goodstart Early Learning, the nation’s biggest not-for-profit provider, has granted pay rises to its 16,000 staff, of between 3 per cent and 5 per cent for educators with certificate or diploma qualifications. Early childhood teachers, who have a four-year university degree, have been given pay rises of between 20 per cent and 50 per cent to give them pay parity with primary school teachers.

Staff also get paid parental leave, a 30 per cent discount on childcare fees and twice the award “programming time” away from children to deal with paperwork.

Even so, Goodstart is having trouble finding enough qualified staff for all its centres and has had to cap enrolments at some because of worker shortages.

“We’re facing an unprecedented shortage of educators and, as the economy bounces back, we’re seeing increasing demand for places,” Goodstart’s head of advocacy, John Cherry, says.

“It’s a very tired workforce, feeling underappreciated by government and the public. We just haven’t been able to replace those who’ve left, and the casual workforce has all but dried up.’’

Goodstart is worried about the lack of university-qualified teachers: Queensland had 300 vacancies for early childhood teachers last month, yet only 300 university students in the state are enrolled in early education degrees.

Goodstart is lobbying the federal government to directly fund a pay rise for early childhood educators.

“We’re chasing our tails,” Cherry says. “The government has to come back to look at wages.”

Childcare will be a social and financial priority for voters in the looming federal election, so the Morrison government has fast-tracked its new subsidy scheme to start in March.

But only 20 per cent of families will benefit financially because extra fee relief will apply only to the second or subsequent child in care.

The biggest benefit to working families will be the removal of the $10,560 annual cap on subsidies paid to families with incomes above $189,390 – often two middle-class parents each earning an average wage.

Labor is promising a less convoluted system, raising the maximum subsidy from 85 per cent to 90 per cent of the fee charged for all children, with the subsidy reducing by one percentage point for every $5000 of family income above $72,406.

Devereux, whose husband David also works full time, has calculated that childcare for baby Jac will cost $2500 a month in out-of-pocket expenses.

With daycare fees rivalling the cost of a mortgage, the couple has put on hold plans to buy a house and will delay having another child until Jac starts school.

“We can’t afford to put two children into full-time daycare at the moment,” Devereux says.

“We’re both from the UK and don’t have family here, so we’re heavily reliant on childcare.

“Australia is a fantastic place to bring up children – the lifestyle is amazing – but when you look at the cost of childcare it’s a challenge.

“In terms of who we vote for in the election, we’ll be going for child-friendly, family-orientated policies and programs.”

The Parenthood, an advocacy group for parents, warns that childcare price rises or shortages will put a brake on Australia’s economic recovery post-pandemic. It notes that 120,000 Australian parents are out of the workforce simply because they cannot find or pay for childcare.

“Families are going to be facing a challenging year with increased fees, less accessibility and a workforce in crisis,” The Parenthood executive director Georgie Dent says.

“Families are already struggling with the cost of care. We’re losing the skilled professionals we really need because you can get paid more working in a coffee shop.

“It’s a really big deal when educators are leaving because children don’t have the opportunity to build trust and a bond.”

Dent wants to see systemic reform of childcare, to stop childcare operators and daycare landlords pocketing every subsidy increase in the form of higher profits.

“We spend $10bn a year in government subsidies and that’s not translated to more affordability for parents, better wages and conditions for educators, or a uniform increase in the quality of the education and care that children receive,” she says.

“Every time additional money is put into subsidies, it gets absorbed in increasing prices and out-of-pocket costs for parents.”

Dent wants childcare to become an extension of the school system, universally available and publicly funded.

“There’s a guaranteed place for every child in primary school, whether your parents are millionaires or unemployed,” she says.

“We don’t expect parents’ fees to subsidise the wages of teachers, and the cost of the land the school’s on.”

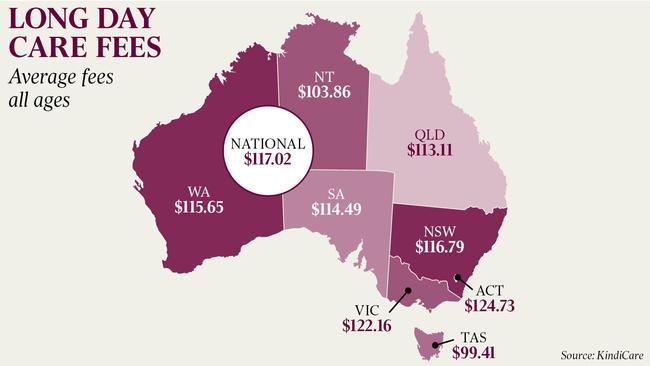

Childcare fees are rising twice as fast as inflation. Daycare comparison app KindiCare has revealed a $5 a day increase in fees, to $117 a day, averaged across 16,500 childcare centres between May and November – a 4.42 per cent increase in the space of six months.

KindiCare founder Benjamin Balk blames staff shortages and sharp rent rises for driving daycare costs higher during the pandemic.

“We’re facing a real skills shortage that will drive up wages and be passed on to parents,” he says.

“Rent is the second largest cost for childcare providers after staff, and childcare assets are one of the hottest areas in the commercial property market right now.

“It’s almost government-backed rent, and pretty recession-proof.”

Commercial property agent Burgess Rawson has flagged childcare centres – along with service stations, bottle shops and fast-food outlets – as “safe recession-proof assets” for investors.

Rents on new daycare centres have soared from $2600 in 2018-19 to $3000 in 2019-20 for each childcare place.

Centres are fetching eye-watering prices as landlords rush to invest in the pandemic property boom – five Melbourne childcare centres fetched almost $45m combined at auction last month.

Hutchinson, who is in a dispute with her own landlord over a Covid-19 rent-freeze request for her two childcare centres in western Sydney, says high rents risk sending some small centres broke.

“The big winners are the landlords,” she says.

“You’ve got developers building centres and selling them off at an insane price, so operators are paying insane mortgage and rents. The rent squeeze and the wages squeeze are driving some operators to the wall.

“There will be price increases (for families), unfortunately.”

The United Workers Union, which represents childcare staff, is furious that foreign private equity investors are “profiting from children”.

The union’s early education director, Helen Gibbons, wants the federal government to force every childcare business to publish their profits and how much tax they pay.

“Australians rightly expect that their tax dollars should fund quality early education and fair wages for educators, not million-dollar CEO salaries, transfers to tax havens and Lamborghinis,” Gibbons says.

As corporate childcare thrives on subsidies, many smaller operators are struggling to survive.

Hutchinson warns that families will be left without formal childcare if centres close in regional and remote areas.

“Families will be forced to do what they did 50 years ago – mothers working shifts to look after each other’s children while the others go to work,” she says.

“We’ll be back to backyard care.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout