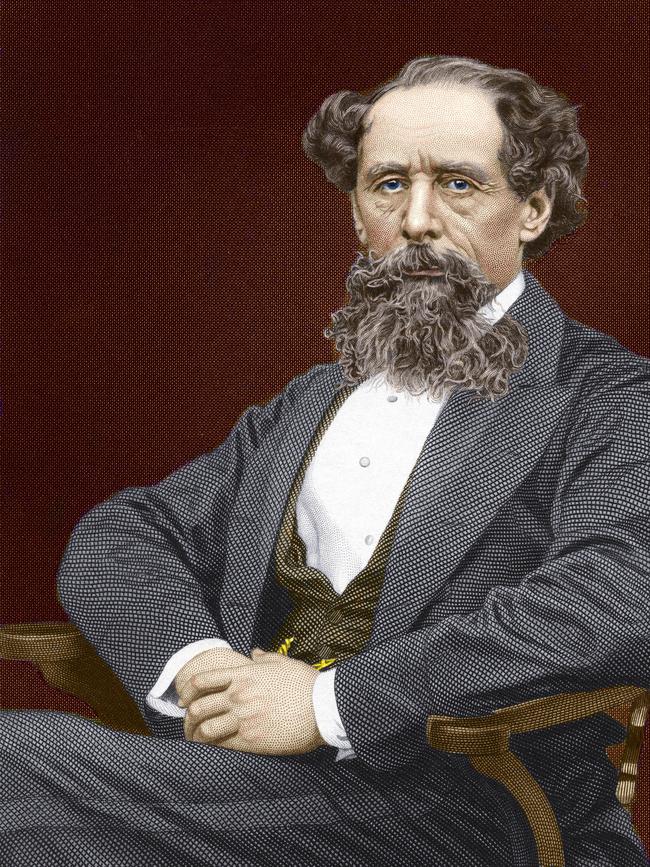

Charles Dickens drawn to Australia’s promise of a second chance

Charles Dickens’ pen is synonymous with the city of London. But he was fascinated by Australia, its prison system and its opportunity to rebuild a life.

There is a running joke among Londoners that Charles Dickens seems to have lived in every second house in the capital, with 43 blue memorial plaques – more than for Queen Victoria – bestowed on buildings where he lived, worked or enjoyed a pint.

Dickens’s pen and the city of London remain inextricably linked in the public imagination two centuries after his death, yet only one house associated with the great Victorian novelist has survived intact.

Today 48 Doughty St, in a tree-lined street of elegant Georgian terraces, sports a jaunty red front door and, as the city returns to life after the long Covid hibernation, it is hung with a festive wreath of ivy and plump holly berries.

It seems fitting that the house where Dickens wrote Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby, and received inspiration for A Christmas Carol, should reopen its doors in time for the festive season.

No.48 is the home where Dickens and his young wife, Kate, held myriad parties and enthusiastically fostered new friendships with London’s thespians, writers and intelligentsia. In 1840 his publishers, Bradbury and Evans, sent him a gift of an enormous turkey, an American import that quickly was replacing goose as the bird of choice for Christmas festivities in England. The bird, he wrote later, was so large it fed the family until January 2. It also would become the centrepiece of one of the great final scenes of his morality tale and Christmas masterpiece.

Dickens’s eldest son, Charley, was born on January 6, 1837, and was a toddler when the family moved to the house, where his father launched an annual tradition of hosting a Twelfth Night party. Guests revelled for hours, enjoying magic lantern projections, conjuring and magic tricks, music, dancing and performances of Dickens’s new work that he staged using family and friends as cast members.

Cindy Sughrue, director of the Charles Dickens Museum, says it was the family home just as the novelist was finding his earliest critical and financial success with the serialisation of The Pickwick Papers. He would finish the series in Doughty St and would welcome two baby daughters with Kate, but he also would also witness the sudden, dramatic death of his 17-year-old sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth, who collapsed one evening after the family returned from the theatre.

“It traumatised him so much that he stopped writing for the very first, and last, time of his life,” Sughrue tells Inquirer. “They were newly married and paid the substantial sum of £80 a year in rent for the house. Charles Dickens was just 25, a little-known writer using the pen name Boz when they moved in. By the time they left he was already an international star.”

The house, kept as it would have been at the time the family lived there, is a treasure trove for the Dickens aficionado and contains the world’s most comprehensive collection of material and artefacts relating to the writer’s life and work. The rooms are filled with his furniture, including a splendid mahogany sideboard he bought and loved, and a reading desk he used when performing his own work and at Christmas would decorate for his parties.

Emily Smith, curator of the house, says Dickens was notorious for hating others’ staging of his work and famously once got down on his knees with head in hands in front of his theatre seat to express his displeasure at a stage adaptation of Oliver Twist: “We have a playbill displayed here of one of the very few he did like, of A Christmas Carol, although he had reservations about that one, too.”

The house’s locks, doors, windows, fireplaces and fittings such as shutters are his, the suit he wore to the royal court is in his dressing-room, even his commode remains by the couple’s bed. Dickens’s writing desk, where he wrote some of his later novels including Great Expectations, A Tale of Two Cities, Our Mutual Friend and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, sits in the study, the angled writing platform marked with ink and the patina of decades of handwriting and his coat sleeve working to and fro.

There are more than 100,000 items in the museum’s archives, items carefully selected and taken out for public display depending on the time of year and themes for the specialist exhibitions.

“This Christmas we have placed on display a little pen holder which Kate gave her husband for Christmas in that second year in the house. It is engraved by hand we think … with a needle. It says ‘To dear Charlie, from Kate Xmas 1838’ … the couple would separate later in life but we know he kept that pen with him, always,” Sughrue says.

“Visitors can also see for the first time lockets exchanged by Dickens and his young sister-in-law.” (The little blue glass heart-shaped locket contains Dickens’s hair, and it is all the more poignant knowing that she had died in the room in which it is displayed, and how her death affected him.)

The museum and its collection of letters, manuscripts, personal effects, rare first editions, prints, paintings and photographs have become a kind of pilgrimage site for Dickens scholars, writers and indeed all lovers of his work. It is an extraordinary experience to look at pages from Dickens’s handwritten manuscript of Oliver Twist, original sketches of Fagin, and letters to friends and family as his fame grew and he published more.

Walking through the museum’s high-ceilinged rooms, it is difficult not to mix the man up with his fictional characters, so often modelled on the real people he met, the places he walked, the city’s inequalities and cruelties that had also shaped his own difficult childhood. Peering into the window of the family’s dining room from the street, it is easy to imagine how the immaculately laid table festooned with fresh fir and greenery for Christmas festivities, the candlelight, warmth and steaming, delicious dishes would have mesmerised poor and hungry eyes looking in.

Dickens’s son Charley, in Reminiscences of My Father, published posthumously in 1934, remembers one Christmas dinner at Doughty St when he was tiny and an invited guest failed to appear, meaning an unlucky 13 would be seated around the table. “I was brought down from the nursery to fill the gap and afterwards set on a footstool on the table closest to my father at dessert time,” he wrote.

His younger sister Mary (Mamie) Dickens would remember and write about the pleasure her father took in seasonal festivities and decorating the dinner table, appointing her to this task when she was still very young. He was a “wonderfully neat and rapid carver”, and when the pudding came out he loved to ensure glasses were filled and a toast raised: “Here’s to us all. God bless us!”

Downstairs in the wash house beside the kitchen there is an original copper, still intact from the Dickens family’s time. Inside the bricked-up space is a large metal bowl with a wooden lid. A fire was lit beneath it and clothes placed inside for boiling and to be stirred with a large wooden stick. For poorer families without kitchens, the washhouse copper would be used to steam the family’s Christmas pudding – a process described in detail in A Christmas Carol.

Dickens’s London may seem a world away from Australia, yet the writer’s fascination for the colony, say the curators, was well known.

There is even a theory, one that Sughrue describes as “quite plausible”, that Miss Havisham of Great Expectations, published in 1861, was modelled on a Sydney woman. Eliza Emily Donnithorne was 31, the last in her family to be married. On the day of her wedding, her family and guests were to celebrate over a nuptial breakfast at her home, Cambridge Hall, then at 36 King Street in Newtown. As Dickens’s story would later unfold, the groom never turned up and his bride-to-be collapsed into darkness and despair, abandoning the celebratory food to rot on the table and becoming a recluse.

There is no conclusive evidence to prove that Dickens based Miss Havisham on Sydney’s Eliza but scholars know Dickens wrote and kept in touch with many friends and researchers who travelled to Australia and he had a keen interest in the colony.

The brutal headmaster of Dotheboys Hall in Nicholas Nickleby, Wackford Squeers, gets his just desserts by being transported to NSW, as does Uriah Heep in David Copperfield when he steals from his employer, Mr Wickfield. The good-natured clerk who exposes the fraud ends up immigrating to Australia as a free settler, becoming an affluent bank manager and a highly respected magistrate. And who could forget Magwitch, condemned to Australia for the term of his natural life in Great Expectations but ultimately Pip’s secret benefactor and wealthy sheep farmer?

Dickens’s friend Alexander Maconochie, a penal reformer, provided him with information on the Australian prison system at the time, allowing Dickens to ponder, in writing, about notions of making good in a new land and being given a second chance.

In fact, Dickens would later encourage his spendthrift fourth son, Alfred, to migrate to Australia aged 19 in a bid to distance him from the “idleness of London”. His youngest son, Edward, would follow his brother a short time later, staying in Australia for 45 years and serving as MP for Wilcannia in the NSW Lower House for five years until he was ousted by the Labor Party in 1894.

Dickens’s fiction was imbued with a potent social conscience and astute observation of the grave injustices ingrained in English society. He was criticised publicly by a Reverend RH Barham, who complained of the “radicalish tone” in Oliver Twist, but Dickens refused to amend it. The much-loved tale was written as a critique of the 1834 Poor Law that aimed to reduce the cost of relief to the poor and remove poverty from city streets. The plan was built on the use of workhouses where the poor were forced to live if in need of help.

Dickens’s passionate humanitarianism was fuelled by his own family’s experience living in a debtors’ prison during his childhood. For him, Australia offered the poor, the downtrodden, the reformed criminal, a chance to rebuild – something he thought entirely impossible in Victorian England.

To learn more about the Charles Dickens Museum, visit dickensmuseum.com.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout