Capital war is a clear and present danger as US weaponises its financial power

The real conflict between east and west is being fought with money, not guns. So why hasn’t China been able to dethrone the almighty dollar?

If Mayer Rothschild were alive today, he would immediately grasp this reality: the nation which controls the international capital flows that enable trade, investment, technology and lifestyles is king. That nation is the US, despite all the talk of its decline. What’s clear is that the US is moving to weaponise its financial power against autocratic challengers opening a new front in the developing cold war with Russia and China.

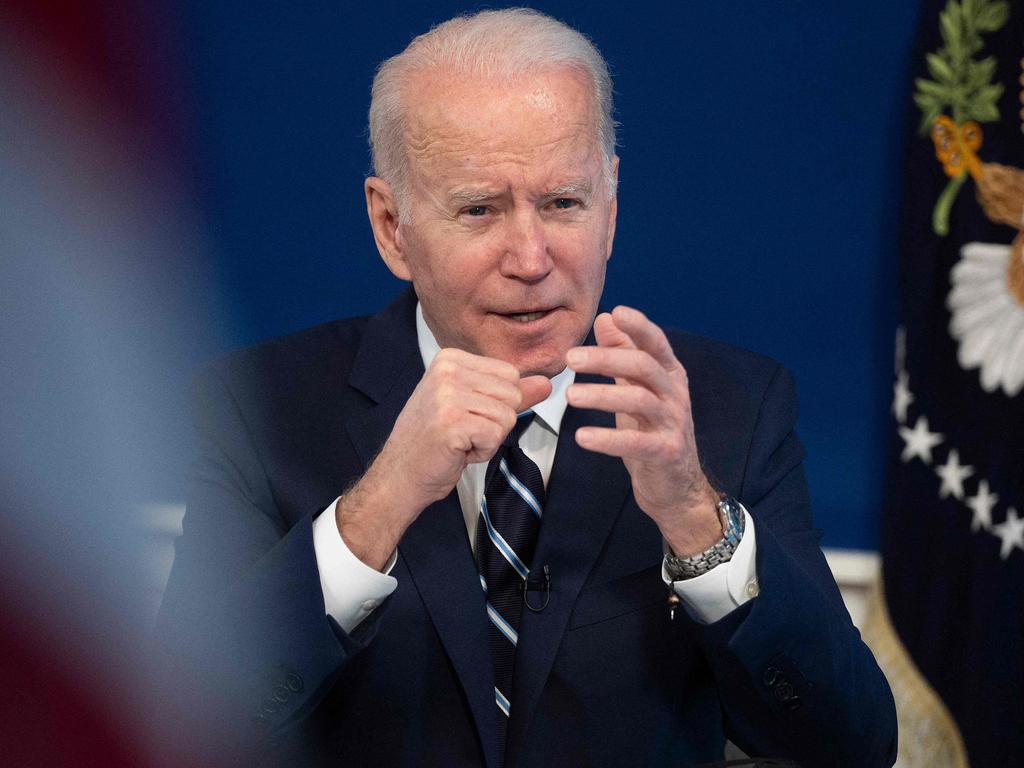

In the confrontation with Russia over Ukraine and the eastern limits of NATO enlargement in Europe, the Biden administration’s trump card is financial not military. Having the world’s indispensable currency gives the US tremendous geopolitical leverage. It could cut off Russia from the world’s banking system.

This would be an unprecedented but enforceable action given the Federal Reserve’s de facto role as the world’s central bank, the US dollar’s reserve currency status and Washington’s prominent role in SWIFT, a secure financial messaging service integral to moving money around internationally. “King dollar still reigns supreme, and that means there are two ways for banks to go: the US way, or the highway,” says financial analyst Nisha Gopalan.

But Washington’s real target is China, for the simple reason that the world’s second-largest economy is the foremost challenger to the US. The Communist Party-state is also vulnerable to US financial pressure because of its reliance on foreign investment and access to the US dollar for economic growth, trade and capital raising. Foreign holdings of Chinese securities now account for nearly two thirds of Chinese foreign exchange reserves, compared with just 5 per cent a decade ago.

The annual report of the US Economic and Security Review Commission provides revealing insights into a rapidly evolving American financial strategy that, if enacted, will make life very difficult for China and its authoritarian soulmates. Western investment in China will be discouraged, creating additional headwinds for an already slowing economy. Beijing is almost certain to resist, raising the prospect of a bifurcated international payments system – a dollar zone led by the US, and a competing yuan-dependent bloc of countries led by China.

Congressional commissions and committees abound in the US but the USCC is no ordinary commission. It was established two decades ago to report to congress on the national security implications of the trade and economic relationship between the US and China. The USSC’s remit and influence have grown enormously in concert with the now bipartisan consensus in congress that the US must use its economic and financial muscle to constrain China. This means that the USCC recommendations will either be legislated or otherwise shape financial regulations.

The report reveals some of the strategies Washington is likely to pursue. The special US trade privileges granted to Hong Kong as a separate customs territory may not survive the former British colony’s loss of political and economic sovereignty in the face of Beijing’s security crackdown. Any interference of the Hong Kong government with the operations of US companies in Hong Kong is to be reported to congress, opening the door to restrictions on capital flows to the island.

Environmental, social and corporate governance considerations will be mobilised to sanction Chinese companies and individuals accused of human rights abuses. The Financial Times’ Rana Foroohar believes that Western financial institutions purporting to prioritise ESG (environmental, social and governance) concerns will come under increasing pressure “to justify the hypocrisies of working with an autocratic government”.

Approaching “US-China capital flows as an ESG issue could be a market mover”, she says.

Another recommendation could have even wider implications – forcing publicly traded US companies with facilities in China to report annually on whether there is a Chinese Communist Party committee in their organisation. According to the CCP’s own figures, 73 per cent of all Chinese firms hosted party committees in 2017, a figure that has almost certainly grown. “It’s hard to imagine a Western company or financial institution doing business in China that wouldn’t have a potential problem,” says Foroohar.

China’s military is also in the USCC’S sights. The report recommends that publicly traded American companies be required to report on “transactions with companies that have been placed on the Department of Commerce’s Entity List or those designated by Treasury as Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies”.

This is particularly significant because US capital has been used to fund Chinese military research and dozens of companies that are fronts for the People’s Liberation Army.

In a recent study, Georgetown University researchers Ryan Fedasiuk and Emily Weinstein found that “even the subsidiaries of China’s state-owned defence enterprises raise funds on foreign stockmarkets to pay for their own advancements in military technology”. According to Claire Chu of RWR Advisory Group, China’s 12 main military-industrial groups had listed 111 publicly traded companies on overseas stock exchanges at the end of 2016.

Losing access to overseas funding would be a hammer blow to Beijing’s economic and military strategies. Despite impressive gains in promoting local innovation, both strategies are predicated on continuing access to Western capital. This has been a critical driver of China’s meteoric rise from economic backwater to developing superpower. Despite the pandemic-induced global slowdown, foreign direct investment into China in 2020 rose by 10 per cent to $US212bn ($293bn).

China may no longer need US capital markets as its own stock exchanges develop. But the CCP is desperate to retain the billions of dollars invested by US companies and wealth managers. It entices American and European investors by promising to make them rich, allowing increased foreign ownership of China’s securities and investment operations as well as bonds and stocks.

Co-opting America’s guardians of capitalism is useful insurance against unwanted financial decoupling. Wall Street reciprocates because it views China as the last great money-making frontier.

The irony is that Wall Street is funding a country whose triumph would signal its own demise, ending the freedoms and rule of law that have sustained the most successful economic system the world has known. Capitalism may have its flaws. But as Winston Churchill might have said, it’s a better system than all the others despite its imperfections.

“What will happen when Wall Street’s aspirations for riches in China meet the political realities of Main-Street America?” asks Foroohar. The answer is congressional hostility towards China could result in a substantial reduction of US capital flows to China and the severing of the cosy relationship between Beijing and the Wall Street moguls.

If congress enacts laws to make it a punishable offence to violate financial sanctions against China, big American banks and asset managers such as Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and mega hedge fund BlackRock may have to withdraw their capital from the country. If they do, the rest of the world will follow. Washington’s financial power and the absence of a viable alternative to the US dollar makes that a near certainty.

No other polity or country has the deep pockets and institutional clout to match the US. Certainly not Europe, despite the advent of the Euro. The yuan is not readily convertible. And China’s share of international payments barely registers. The US dollar accounts for about 45 per cent of all payments and nearly 90 per cent of global financial transactions involving banks.

When borrowing from overseas, companies and individuals overwhelmingly prefer dollar-denominated loans, and 75 per cent of all overseas borrowings are in US dollars, up from 60 per cent 15 years ago. The US has strengthened its hold on the international banking system in recent years because of the rising debt problems of Chinese, European and Japanese banks. It also has the world’s largest and most accessible stock and bond markets.

Writing in the influential US policy journal Foreign Affairs, the chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, Ruchir Sharma, says that the US has staged a remarkable comeback as an economic power and financial empire since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. This he attributes to its relatively young population, open door to immigration and investment pouring into Silicon Valley fuelling the rise of Big Tech.

But the key reason is the reserve currency status of the US dollar, which has been a “perk of empire” for every country that has held this title since 15th century Portugal. “What the rest of the world wants in a reserve currency is a vast, liquid market in which people are free to buy and sell without fear that the government will suddenly change the rules,” says Sharma.

As Rothschild predicted, since the Federal Reserve controls the supply of dollars, when it increases interest rates every other central bank, including China’s, comes under enormous pressure to move in the same direction or face destabilising capital outflows. And because the global demand for US dollars is insatiable, Washington can sustain deficits it could not otherwise afford by issuing government-backed bonds. It is this power which gives America what former French president Valery Giscard d’Estaing once called, “an exorbitant privilege”.

China, and fellow autocracies, have tried without success to lift king dollar’s crown. Commanding barely 2 per cent of the world’s gross domestic product, Russia simply doesn’t have the necessary economic or financial weight. But China does.

Its share of global economic power has grown from 2 to 16 per cent over the past four decades and its share of money stock is almost double that of the US ($US28 trillion to $US16 trillion). It is also the market leader in e-commerce and associated financial technology, an important indicator of innovation and future economic strength.

Unlike the West, online shopping platforms in China routinely “blend digital payments, group deals, social media, gaming, instant messaging, short videos and live-streaming celebrities”, says The Economist.

So why hasn’t China been able to dethrone the almighty dollar? The answer, says the Hinrich Foundation’s Stewart Paterson, is “China’s capital controls, a mercantilist approach to foreign reserves, and the relatively closed and retarded nature of its capital markets” – the exact opposite of US strengths.

These weaknesses were illuminated by the steady flow of money out of China when capital controls were loosened in the first half of the previous decade. This turned into a yuan tsunami when the Shanghai stockmarket crashed in 2015, forcing Beijing to reinstate capital controls.

But the contest is far from over. Washington’s overuse of financial sanctions as its default policy response to competitor actions it doesn’t like incentivises Beijing to keep chipping away at the dollar’s supremacy. It’s not without options. They include taking steps to further internationalise the yuan and accelerating the development of a digital currency as a means of bypassing the established remittance system.

China’s central bank is already trialling a Digital Currency Electronic Payment System. Over time, this could provide an alternative for countries intent on evading US sanctions or wanting an alternative to the US dollar.

Paterson says that “if the digital yuan and its payments system were to provide increased efficiency, faster settlement and lower transaction costs with clearing through a central bank potentially with payment guarantees, then it could outcompete the incumbent system of international payments network”.

China’s massive trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative, supporting infrastructure projects that stretch across half the world, “may provide the perfect testing ground for the internationalisation of the digital yuan”. It’s conceivable that signatories to the BRI with weak domestic currencies, beholden to China, could join anti-American autocracies in forming a yuan bloc.

Should the Biden administration weaponise its financial power, Beijing could attempt to fight with fire by selling off its $US1.1 trillion in US Treasury holdings, as hardliners urge, causing a run on the dollar. The problem is that the so-called “nuclear option” could destabilise the global financial system and cause serious collateral damage to China by reducing its money supply and making its exports more expensive. And the US could simply replace China’s holdings by printing more dollars.

But the real threat to the continuing hegemony of the US dollar may not be China – or any other nation for that matter. It may come from within.

Complacency, budgetary improvidence and rising debt are eroding the foundations of America’s financial empire. In 1985, says Sharma, “the United States owed the rest of the world $US104bn, an amount equal to a negligible 2.5 per cent of GDP. Since then, those liabilities have risen to nearly $US10 trillion, or 50 per cent of GDP, a threshold that has often pushed nations into a currency crisis. Empires lose their reserve currency status when foreign nations lose confidence that the imperial power can pay its bills.”

The historical record supports Sharma’s contention that there is nothing preordained about the dollar’s dominance. Before the US, five nations had held reserve currency status – Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, France and Britain. On average, each held this coveted status for 94 years. The US dollar’s tenure is now 102 years. Sometime in the future the dollar’s run will come to an end.

Fortunately for liberal democracies, which have prospered on America’s watch, that moment has not yet arrived. But this will be little consolation if the US wields its financial power as a sledgehammer, rather than a scalpel.

A capital war would roil already skittish markets; undermine the fragile post-Covid economic recovery; spur the emergence of a competitive China-led payments system; and accelerate supply chain and technology decoupling between the world’s leading democracies and their autocratic challengers. There’s little sign that governments, financial institutions, asset managers and ordinary investors are alert to the risk.

Alan Dupont is the chief executive officer of geopolitical risk consultancy The Cognoscenti Group and a nonresident fellow at the Lowy Institute.

“Money makes the world go around” sang the incomparable chanteuse Liza Minnelli in her 1972 musical film hit Cabaret. The founder of the storied Rothschild banking dynasty said much the same thing nearly two centuries earlier but in words that have profoundly shaped the structure and power realities of the international financial system. “Permit me to issue and control the money of a nation, and I care not who makes its laws,” opined Mayer Anselm Rothschild in 1790, a year before the establishment of the First Bank of the United States.