Canberra transformed as broken trust, revenge politics take hold with royal commissions and NACC

Governments are weaponising royal commissions, and flawed politicians are making it easy. We are witnessing a permanent change: the judicialisation of politics.

The instrument of moral punishment and conversation is the royal commission run by a judicial officer whose findings become the received wisdom and allow guardians of the public interest to demand they be implemented “with the full force of the law”.

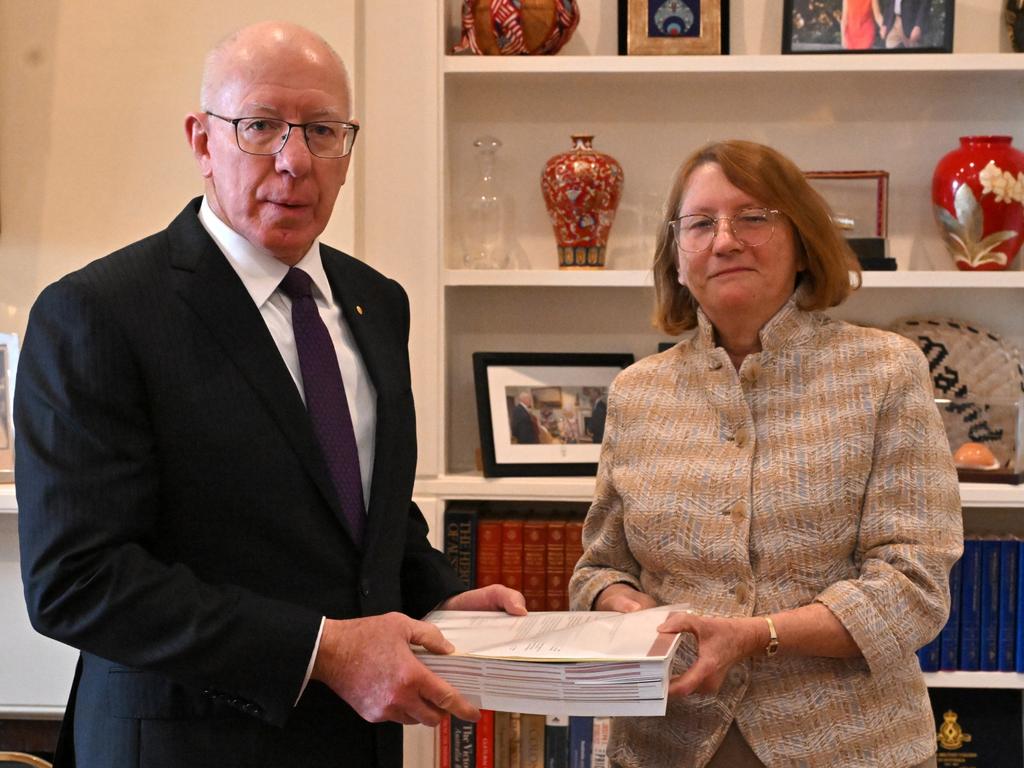

The transformation is highlighted by the newly operational National Anti-Corruption Commission under former judge and distinguished lawyer Paul Brereton with the NACC functioning as a variation on a permanent royal commission while the nation is absorbing simultaneously the spectacular conclusions of the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme presided over by Catherine Holmes, former chief justice of Queensland.

The “politics is broke” mentality runs deep, provoked by high-level blunders with Robodebt being the latest and most grievous, exposing systemic failure within the public service advisory process, not just by former Coalition ministers. Allegations of improper behaviour by politicians are now a routine tactic, sometimes justified and other times merely ingrained cheap ploys that discredit the system.

The Robodebt royal commission was established by the Albanese government on August 25 last year following its election promise. Anthony Albanese knew what he was doing – he called the scheme a “cruel system” and a “human tragedy”. Government Services Minister Bill Shorten said the Coalition had delivered “robo-victims” and “robo-denial” while Labor would give victims “robo-justice”.

The royal commission was entirely justified. As Shorten said, Robodebt constituted “a shameful chapter in the history of public administration in this country”. The great former Country Party leader, briefly prime minister, and born humorist Arthur Fadden once said: “Never have a royal commission unless you know the result.” Labor followed the Fadden dictum. It knew the result, except for the sealed section.

The new modus operandi is surely established. An incoming government holds a royal commission into the scandals or nefarious activities of its predecessor. It constitutes a brutalised revenge play on the opposing side with the public and media as applauding spectators demanding retribution. It is likely to become standard tactics for incoming governments.

The former Abbott government thought it was being clever in 2013 and 2014 when it created royal commissions to investigate Labor’s “pink batts” insulation scheme (where four people died) targeted at Kevin Rudd and then trade union governance and corruption targeted at Shorten.

This is no reflection on the royal commissioners. But the political motive in these cases was overwhelming while the political gain for the Liberals proved marginal, if any.

Labor has repaid the technique in spades. It has shown the Liberals how to do the job. For a government the perfect royal commission is solely justified on merit but comes with political gain – Robodebt being a classic example. The Liberals will suffer from this exposure all the way to the next election.

For Albanese, it was too easy. What did he do the day after unveiling the Robodebt royal commission? He announced an inquiry into Scott Morrison’s blunder of assuming multiple ministries to be conducted by former High Court judge Virginia Bell. The justification was to uphold the principles of our constitutional democracy. The findings, as expected, were lethal.

John Howard once said: “I’m uneasy about the idea of having royal commissions or inquiries into essentially a political decision on which the public has already delivered a verdict.” That notion has passed into history.

Royal commissions in their finest form are nation-changing events. While they cannot be divorced from politics, a new phenomenon is under way – they are increasingly being used to discredit the opposing side in the name of exposing failures of integrity. As everything becomes politicised, the demands for royal commissions are politicised. Hardly a week passes without a politician, lawyer, activist or journalist calling for yet another royal commission.

Often the call is an end in itself; witness Shorten’s calculated demand as ALP leader for a royal commission into banking and finance, a populist call that infuriated and damaged the Turnbull government until it finally succumbed, with the final results fully justifying the idea.

The Holmes Robodebt investigation has done a public service, with many sensible reform recommendations; but it also embodies the lawyers’ scepticism of untrustworthy politicians, with Holmes backing more transparency in cabinet decision-making, elimination of the blanket exemption of cabinet documents from disclosure and suspicion of how cabinet responsibility is applied.

The inception of the NACC seems certain to change our politics in two ways – it will make parliamentarians and public servants more careful and hopefully put a premium on probity, and it will be weaponised for political gain, given its immense powers and standing, just as politicians increasingly seek to weaponise royal commissions.

Wide scope remains for further investigations into the former government. After 10 days since its inception the NACC revealed it had received 311 referrals with about 54 per cent concerning issues “well publicised in the media” – presumably including potential corruption allegations against federal politicians.

That’s no surprise. During the election campaign last year Albanese routinely called the Morrison government ministers corrupt as part of his support for the NACC. The Greens already have announced their “top 10” list of NACC referrals and they include Robodebt, Morrison’s multiple ministries (yet again), former minister Stuart Robert over government contracts, former minister Angus Taylor on two separate issues and the so-called sports rorts where the focus was former minister Bridget McKenzie.

The Greens have repeated the claims of other activists that the NACC must investigate “how to end the damaging practice of pork barrelling” – a project in futility but convenient for the Greens in suggesting the political system itself is endemic with cover-ups and sleeze.

It is a safe bet some of the referrals are against Labor, given that Liberal leader Peter Dutton has supported the referral to NACC of the Albanese government’s compensation payout to Brittany Higgins. Dutton’s approach is obvious: given the rules of politics have changed, the Coalition needs to operate by the new rules.

Both sides of politics are going to engage in the management of referrals. Will this emerging model enhance or diminish public faith in our system? This question requires a rational debate, not the typical propaganda that is dished up.

The NACC functions as a parallel form of integrity and corruption arbiter to the established court system. It can make a finding of corruption against a parliamentarian or public servant if they are deemed to breach public trust. Conduct can be corrupt without being criminal, as the Gladys Berejiklian case showed.

The critical question will become Brereton’s skill and judgment in deciding which officials or politicians to investigate further and what to publicise. The operations of the NACC will change both official behaviour and have enormous consequences for either side of politics, dependent on its judgments. The operation of the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption shows that once a politician is identified for investigation that is a career-ending event. How many ministers, Labor and Coalition, do you think are on the NACC referral list so far? This is a new form of political competition.

Holmes in her Robodebt report made findings against several public servants and former Coalition ministers and was prepared to do so in cases without “direct evidence” but relying on circumstantial evidence. That’s the power of a royal commission. Holmes called the scheme “a crude and cruel mechanism, neither fair nor legal, and it made many people feel like criminals. In essence, people were traumatised on the off-chance they might owe money.”

In the end, the Morrison government had to reimburse $746m to 381,000 affected individuals and write off debts amounting to $1.751bn. The scheme caused pain, desperation and suicide. It was initially approved on a misleading cabinet submission from Morrison in 2015 when he was social services minister. Holmes said it was perpetuated after the start of 2017, the point at which “Robodebt’s unfairness, probably illegality and cruelty became apparent” and that “it should then have been abandoned or revised drastically”.

In releasing the report Albanese highlighted its findings against Morrison and former ministers Alan Tudge, Christian Porter and Robert. These findings are contested.

Albanese praised the courage of the victims who came forward and damned “those who sought to shift the blame, bury the truth and carry on justifying this shocking harm”. In reality, this is a failure of competence and morality. It will hang around the neck of the Liberals for years.

The royal commission report is written with forensic analysis, deep feeling and some extravagant conclusions. Take one example. Examining the initial 2015 decision to establish the scheme, the main finding against Morrison is “he failed to meet his ministerial responsibility to ensure that cabinet was properly informed about what the proposal actually entailed and to ensure it was lawful”. The report spends many pages dissecting how this happened. Holmes refuses to accept Morrison’s statement that he believed income averaging – the flawed method at the heart of Robodebt – was an established method. She says it is “very unlikely” the department told Morrison this and concludes his statement was “untrue”.

The case against Morrison, however, essentially boils down to Morrison accepting his department’s final cabinet submission at face value, saying that no legal change was necessary to authorise the scheme. This reversed earlier advice that legislative change would be needed. The earlier advice was correct and the final advice in the cabinet submission was wrong.

The critical event was cabinet’s expenditure review committee meeting on March 25, 2015, preparing for the 2015-16 budget, when the scheme was authorised. The royal commissioner said of Morrison: “The proper administration of his department required him to make inquiries about why, in the absence of any explanation, DSS (the Department of Social Services) appeared to have reversed its position on the need for legislative change … He chose not to inquire. Mr Morrison allowed cabinet to be misled because he did not make that obvious inquiry.”

Morrison failed to ask a question. That’s it. Holmes builds a mountain on this omission, which she insists should have been “obvious”. Opinions may differ about that. It is a problem long familiar for anybody who has studied public administration with its eternal question: Who is to blame, the minister or the public servant?

Morrison released a statement attacking the report’s findings about himself as “wrong, unsubstantiated and contradicted by clear documentary evidence”. He expressed regret at the scheme’s consequences and said there were “important lessons” to be learned. Nobody took his defence seriously and Labor accused him of lacking contrition.

There seems to be concern the former Liberal ministers may escape without penalty. Tudge, Porter and Robert are no longer in parliament. Morrison is leaving. How can they be penalised? In a significant intervention Shorten told the ABC he questioned why former ministers “think there’re out of the woods”. Shorten has read his report. At the end Holmes regretfully argued that a compensation scheme won’t work because individual circumstances differed and across-the-board compensation criteria cannot be applied. But she said “elements of the tort of misfeasance in public office appear to exist” and “people may have individual or collective remedies”. That’s an invitation. It leads to another possible legal recourse: the pursuit of damages against the former ministers.

Shorten raised this spectre, saying the victims might “sue them individually”. When the Federal Court found against the government in the class action over Robodebt, the judge said if one needed to choose between a stuff-up and a conspiracy, then it’s normally a stuff-up. But the Holmes report suggests the reverse interpretation.

Her report, however, is more severe on the senior public servants than the ministers. Addressing the role of the public service in the Pearls and Irritations online journal, economist and former head of the Prime Minister’s Department Mike Keating said the defect in Robodebt would have been widely known – using the flawed method of taking the fortnightly average of the recipient’s annual income as recorded by the Australian Taxation Office to assess whether there had been overpayment of benefit.

Keating said: “I worry about the quality of the policy judgment and advice from the Australian Public Service under Morrison, and not just in the relevant departments, but also in the key agencies.” He said the public servants, given their knowledge and the data, should have advised ministers against Robodebt.

This is surely the core point. The public service should have given strong advice about the dangers in the Robodebt model. Instead, it wanted to accommodate the government. Keating concludes that the task for the Albanese government in restoring public service capability is much bigger than just getting rid of a few rotten apples. “The quality of professional advice needs to be lifted across the public service,” Keating said.

Consider Holmes’s conclusions about the role of the secretary of the Department of Human Services, Kathryn Campbell, whom she said knew the document going to the ERC cabinet meeting “was likely to mislead cabinet because it contained no reference to income averaging or the need for legislative change”.

Campbell said in evidence the misleading effect was an “oversight”. Holmes does not accept this. She said: “The weight of evidence instead leads to the conclusion that Ms Campbell knew of the misleading effect … but chose to stay silent, knowing that Mr Morrison wanted to pursue the proposal.”

Relations between the public service and the former government were compromised with serious fault on both sides. In his evidence Morrison said the Robodebt scheme was “initiated within the public service and brought to us”. Holmes says this is “entirely correct” but then says it is “to ignore part of the story”.

What part is that? She says that public servants were feeling under pressure from Morrison given his comments about “ensuring welfare integrity” and being a “welfare cop on the beat”. The minister was focused on a “drive for savings”. Holmes highlights this climate as a factor in the overall failure.

She doesn’t seem to mention, however, that the social services budget for 2015-16 was $154bn, easily the biggest spending functional outlay, that the Abbott government’s central purpose was to return the budget to surplus on behalf of Australian taxpayers, that every minister was involved in the pursuit of savings and that it was the responsibility of all departments to contribute to this goal.

This cannot excuse Robodebt. It helps to explain Robodebt because public servants made inexcusable blunders seeking such savings. But any implication that the drive for savings in social services was misplaced is surely a stretch too far.

In coming months the focus will remain on the new NACC. It is noteworthy that Brereton in his opening comments delivered a tough message: he won’t tolerate any effort to “weaponise” the commission for political purposes. Hopefully, he can deliver on that pledge.

Australia is now being transformed into a new model best seen as the judicialisation of politics. The change is permanent and comes with pluses and negatives. But it is beloved by the public, the media and legions of lawyers in their quest to expose bad behaviour and the immorality of politicians.