Can we still love a woke, insiders’ Qantas?

The decline of the Qantas good name encompasses several fairly tragic tales of modern Australia. While its bottom line is in rude good health, is it a fallen icon?

Now, as its long-time impresario, public face and emperor Alan Joyce quickly scuttles off into the sunset, Qantas is the nation’s most complained about company. Its service is mediocre, it’s wildly expensive and involved in a bewildering conflagration of controversies.

The decline of the Qantas good name encompasses several fairly tragic tales of modern Australia, a land of ineffective governance, modest and patchy performance, unjustified complacency, debilitating cultural confusion, and a growing divide between insiders and outsiders, between the Chairman’s Lounge and cattle class.

It’s hard to know who has handled controversy worse, Qantas or the Albanese government.

In July, Transport Minister Catherine King refused a request from Qatar Airways for 21 more flights a week to Australia’s main airports. That’s a million extra seats coming to Australia every year. The benefits in tourism alone would be hundreds of millions of dollars, plus the extra freight capacity and greater choice for Australian flyers.

Plus inevitably lower airfares. Jayne Hrdlicka, Virgin Australia chief executive, claims it could have lowered airfares by 40 per cent. King labels such estimates ridiculous.

The big beneficiary of the Qatar Airways decision is Qantas – no extra competition from a superior airline, no need to reduce punitive airfares.

Simultaneously, the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission has taken action against Qantas in the Federal Court. The ACCC says Qantas sold tickets for more than 8000 flights it had already cancelled. It wants a penalty in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Qantas also had to backflip on its policy to extinguish by December 31 more than $500m worth of flight credits from the Covid period still held with Qantas and Jetstar by travellers in Australia and overseas. Qantas had made it quite hard to redeem credits. Not only were there, until very recently, the familiar epic telephone wait times but customers can’t use a credit even for a spouse or child.

Other airlines accuse Qantas of “slot hoarding”. Sydney airport has a limited number of landing slots. Qantas holds a huge number. Even now Qantas is not flying at its pre-Covid capacity but retains many slots it never uses. This prevents competition.

The Qatar Airways controversy has a way to run. Opposition transport spokeswoman Bridget McKenzie has succeeded in setting up a Senate select committee to investigate the decision.

In parliament this week the Albanese government looked all over the shop like a bad baby’s breakfast. It couldn’t answer simple questions, couldn’t sustain a coherent explanation for the decision. It looked rattled.

It’s worth taking a step or two back from the immediate controversy to consider what it reveals about our society and economy. Our economy is a mess. Our productivity is declining. Throughout the past year the amount of economic activity we produce per hour fell by 3.6 per cent. We are in a per capita recession. The economy is notionally growing because of high immigration, but per capita income has declined two quarters in a row. The government is busily re-regulating industrial relations so that flexibility and productivity will decline further.

But our powers of self-delusion remain formidable. Anthony Albanese said Australia had the world’s most competitive aviation market. That’s just wrong. In our domestic aviation market, more than 95 per cent of flights are undertaken by two airlines, Qantas and Virgin.

Tony Webber, former chief economist for Qantas, now chief executive of Airline Intelligence and Research, has conducted exhaustive analysis of Australia’s international aviation market and finds there are only eight routes Australia flies that are more competitive than our domestic market, with 20 routes even less competitive than our domestic market. Webber concludes we are “a far cry from the most competitive (aviation market) in the world”.

Meanwhile, Qantas, rightly in my view, cannot be sold to majority foreign ownership. Whatever that adds up to, it’s not a free market. I’m no apostle of free market absolutism. I think it’s good that we have a majority Australian-owned airline. Geoffrey Blainey, our most distinguished historian, tells Inquirer: “BHP and Qantas were both seen as nation-building organisations and enjoyed enormous support.”

But Qantas’s size and influence no longer are seen as particularly good for many Australians. There is the poor quality of service, the endless cancellations and delays, and the arrogant, prissy bossiness of Qantas, which tells its passengers what to think about every issue from gay marriage, to Israel Folau, to the proposed Indigenous voice to parliament.

Yet the Qantas bottom line looks great; a full year profit of $2.47bn just about matches the $2.7bn it got from the government during Covid.

Qantas is emblematic of the Australian economy. We are assuredly not a socialist economy, but neither are we a free market economy. We are really a fat and lazy oligopolist economy whose luck may be running out. We’re a cosy corporate state kind of dozy economy.

Of our five biggest companies, none was founded in the past 100 years.. The rate of new business formation is very low. A few years ago a landmark Harvard Kennedy School of Government study found that while Australia was the eighth richest country, for economic complexity we ranked a pitiful 93rd. We are wealthy because we sell huge amounts of minerals. The rest is noise around our lavish, quarrelsome efforts to redistribute this wealth.

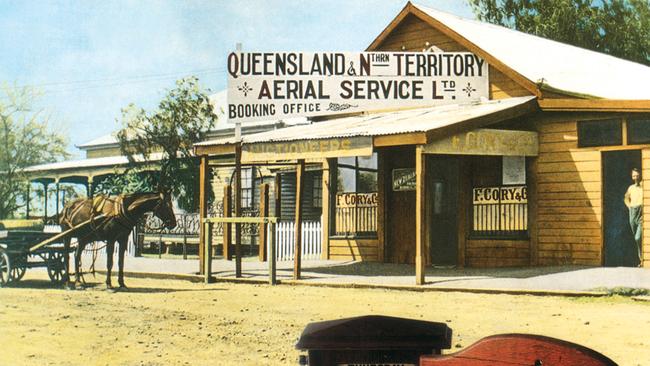

Qantas tells our story. Founded in 1920, it was a magnificent pioneer. It ran the first Flying Doctor Service, another icon. After World War II it was taken into government ownership and became part of our magnificent decade, the swirling 1950s, when Australia believed in itself as never before. It was privatised, part of the Hawke-Keating reforms, in the early ’90s.

So many of Australia’s biggest companies – Commonwealth Bank, Telstra, CSL, Qantas – are former government corporations.

Qantas now inhabits a kind of grey zone. It is no longer government owned so it isn’t held directly accountable through the political system, parliamentary questions to the shareholding ministers and the like. At the same time, it’s not disciplined or held accountable by full-blooded competition. It is, par excellence, a central part of the cosy oligopoly of our political economy. Qantas is notionally regulated by the government. But as many key figures put to me this week, Qantas in effect has captured the regulator. Former Liberal treasurer Peter Costello hails Qantas as the most effective lobbyist in Australia.

The Australian Financial Review has run a campaign concerning Qantas giving a membership of its exclusive Chairman’s Lounge to the Prime Minister’s son, Nathan. I have asked many Chairman’s Lounge members, including former prime ministers, whether their membership ever extended to any of their adult children. No one had heard of such a thing. It goes without saying that there is not a speck of discredit attaching to Albanese’s son. But this is really not a good look, not at all.

Zoom the lens out a bit more. Travelling through the Qantas terminal at Melbourne for a domestic flight is an exercise in class distinctions. Cattle class buy their coffees, for as much as $7 a cup, in the crowded public facilities. The public toilets are often pretty crook too.

One level higher up is the Qantas Club, basically for frequent flyers above a certain points threshold. You get barista coffee for free. The club is often crowded but pleasant. A narrow range of snacks is available, a few desks where you can plug in your laptop, one or two TVs on news stations, though the volume is too low to hear. There’s no outside window but a narrow section with an interior view of the check-in hall.

One step better is the business class lounge. Here are floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking blue skies and the endlessly absorbing rituals of tarmac management, with planes coming and going. A much wider range of food and drinks are on offer, more folks making the coffee, shorter queues.

Beyond this is the highest level, the Chairman’s Lounge. Here is an Elysian oasis, a balm for the spirit. It’s hushed and spacious; discreet staff take your order for poached eggs or smoked salmon, the finest wines are brought to your lounge, attentive staff fix boarding passes and flight arrangements. Here the great and the good, and all federal politicians, mingle.

It’s a remarkably stratified, graded, social class experience for such a notionally egalitarian nation. I’ve been to most of the Qantas Chairman’s Lounges in Australia, only as someone’s guest of course. Most airlines around the world have privilege lounges. Qantas gives a lounge membership to every federal politician (yes, the Greens revolutionaries lap up the bosses’ champagne), many senior public servants and titans of industry. It’s sublimely effective corporate lobbying.

The whole nation in a way is in on the Qantas fix. Because foreign airlines are so restricted in Australia, and in our domestic market, Qantas is more or less a monopoly, and it makes sense for everybody to invest effort into their Qantas frequent flyer membership.

All this cosiness, however, leads to seriously sub-optimal outcomes. Webber points out to Inquirer that Qantas is still operating below the capacity it had before Covid, while many foreign airlines have been kept out or kept below the level they want to operate at.

He says: “Qantas keeps capacity at pre-Covid levels, drip-feeds extra capacity into the system very slowly and generates huge profits by charging very high fares.” With capacity way below demand, oligopoly delivers monopoly profits.

Here’s where absolutely everything about the Qatar Airways decision looks terrible.

It would be wrong to demonise Joyce. In his early years as chief executive he perhaps saved the airline. As a former government corporation, Qantas received huge advantages on its privatisation, not least that its debt was forgiven. And it has enjoyed huge regulatory advantages ever since. But it also had legacy issues, especially entanglement with the old industrial relations system, with all its inefficiency and enterprise-killing irrationality.

The Albanese government is busy restoring the worst features of the old IR system, which will be another drag on the economy. Joyce had the courage to break the union stranglehold on Qantas. It was a tough battle. He pioneered the immensely successful partnership with Emirates. And his plans to fly direct, non-stop flights from east coast Australia to London and New York are visionary. But he stayed too long, became too arrogant and way, way, way too political. Recently Joyce committed Qantas to supporting the Yes campaign in the voice referendum. This is a partisan issue, the government on one side, the opposition on the other. Half the nation is against the idea. But Joyce paints Qantas planes with a Yes sign and offers to fly Yes campaigners around Australia for free, not doing the same for No campaigners. It’s unaccountable political power. It’s undemocratic.

And how does this all look? Qantas does personal favours for the Prime Minister’s family, then publicly commits in a big way to the government’s most controversial political campaign, and then – “Deidre Chambers what a coincidence!” – the government takes an irrational regulatory decision that keeps out a Qantas competitor and contributes directly to the Qantas bottom line.

No doubt everyone’s motives are pure, but it’s a horrible look. Dutton and McKenzie flatly accuse the government of “running a protection racket for Qantas”.

Joyce’s arrogant political campaigning is inherently undemocratic. The No campaigners, however, believe popular resentment at Qantas’s constant political hectoring is one of their greatest assets, as people react against Qantas bossiness. Not only does Qantas instruct the public what to think on same sex marriage, Israel Folau and the voice referendum but on every Qantas flight there is a welcome to country and/or an acknowledgment of Aboriginal elders. In a secular and egalitarian democracy like ours, this is both absurd and potentially dangerous. At the height of Australia’s adherence to formal Christianity, it was only spasmodically that at a normal public function someone was called on to say grace. Australians were generally allowed whatever private thoughts they liked.

But now the worship of woke identity politics is so severe that we must genuflect in pious prayer to it several times a day. Resentment at these absurd rituals is not resentment at Aboriginal Australians. But Qantas will generate such resentment in time.

Part of today’s corporate political activism is to earn goodwill from governments, but it also springs from the ESG movement, for companies to act and invest in approved environmental, social and governance ways. This means global warming schtick and left of centre identity politics.

John O’Sullivan, in the September issue of Quadrant, argues Western nations are developing into “managerial party-states, softer than China but rooted in the same social-credit system of control”. He quotes NS Lyons: “There can be no neutral institutions in a party-state. The party-state’s enemies are the institution’s enemies, or the institution is an enemy of the party-state (which is not a profitable position to be in).”

People are annoyed with Qantas mainly because of punitive airfares, endless delays and cancellations, low standards of service generally, the often shabby state of the planes (certainly compared with Asian or Middle Eastern airlines), and until recently the water torture insanity of trying to get through to it on the phone. Oh, and the fairly obscene size of Joyce’s remuneration and bonuses. But Qantas’s politics play a part too. Many people disagree with Qantas over the political issues it spruiks, using shareholders funds and inflicting propaganda on innocent travellers.

If you’re annoyed about that sort of thing, when Qantas is criticised your reaction is not so much protective of an Australian icon – who shot Bambi? – but, rather, I’m glad somebody cut those bullies down to size.

Qantas has become dangerous for the Albanese government. It cannot any longer deploy its goodwill to assist the government on political issues. Instead it generates resentment as part of the elite celebrity culture that is so spectacularly out of touch with normal reality.

The government in parliament this week seemed to be reciting the most ludicrous of Qantas’s talking points. Early on one minister said the Qatar Airways decision was to help Qantas, another that it was to secure Australian jobs, then that it would distort the market if Qatar had too many flights. Then according to King there were vague and slightly sinister “national interest” reasons. Then King said it was partly because some Australian passengers had been subject to grossly improper invasive searches at Hamad airport in 2020, though this had certainly not been Qatar Airways’ doing. Foreign Minister Penny Wong even rang the Qatari Prime Minister this week to speak about the incident. She’d never done so before. It looked like a grubbily transparent effort to throw up a smokescreen of distraction around a plainly absurd decision on Qatar Airways.

The Prime Minister and other ministers repeatedly said Qatar Airways was welcome to increase its capacity at Adelaide, Cairns, the Gold Coast, Canberra. None of these makes sense for Qatar Airways. But if there’s some moral offence quotient in stopping it from competing against Qantas in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth, surely the same moral reasons apply in Adelaide, Canberra etc.

Sky News journalist Andrew Clennell made surely the shrewdest remark: “Sometimes in these cases it’s actually best just to tell the truth.”

Oligopoly economies have their appeal. They tend to be stable. All the big players have their assured place, everyone tries for a cut, or a crumb, of the pie. But they are also complacent, stagnant systems. The bar to entry is too high. The demand for goodies is insatiable. The growth potential is slow. Ultimately they can’t pay the bills, ultimately they explode in frustration

We live in a time of economic stagnation and cultural dislocation, a time of so many fallen Australian icons – Holden out of business, AMP charging dead people premiums, the Commonwealth Bank’s scandals, the Wallabies forgetting how to play rugby, Captain Cook, Rolf Harris. The success of the Matildas in the women’s World Cup briefly gave us back one icon; for a short moment we were allowed to sing and celebrate Waltzing Matilda again. Once our national song, it has been latterly banished by woke.

Is Qantas a fallen icon now? The Qantas bottom line is in rude good health. But do we still love it?

Once, the nation loved Qantas with abandon. The little Aussie battler that started off in Winton more than 100 years ago and grew up to be a national champion, the spirit of Australia, the flying kangaroo. Once, every Australian hoped that if they flew, it would be Qantas.