Cardinal George Pell: Can Rome stand by its man?

Some of Pell’s closest supporters are deeply frustrated with the way they believe the child sex abuse royal commission has ‘gone after’ the cardinal.

The Vatican has one more big call to make on George Pell: How to respond to a deeply unflattering royal commission account of what the cardinal knew, and when, in one of the church’s more corrupt and neglectful patches of dirt.

The Vatican will likely want to hold the line, retain 78-year-old Pell as a cardinal and work on the assumption that the scandal will gather dust as quickly as the inquiry volumes on commissioner Peter McClellan’s shelves.

But it would be a profound mistake if the lessons of Ballarat and Melbourne were to be lost in the fog of compassion fatigue.

The Pell story always has been one of common sense and it is now a story of two parts.

First, the botched cathedral convictions.

Now a royal commission narrative that digs deep into the 1970s and beyond, when the church leadership and its underlings so spectacularly lost their way.

The second part of the Pell story reflects poorly on the cardinal if you follow without question the royal commission narrative.

This week’s unredacted royal commission commentary, which was hyper-critical of Pell in parts, was not surprising.

The commission has never felt like a body that was ever going to be anything other than scathing of the cardinal, linked as it was with the same police taskforce that eventually charged Pell of multiple sex offences.

The commentary that Pell’s evidence on abusive priests Gerald Ridsdale and Peter Searson was “implausible’’ is searing. The commission didn’t call Pell a liar but it might as well have.

The scaffolding for the narrative around Pell’s responses to abusive priests was built on what the commission found were his concerns, knowledge or information about paedophiles in the Ballarat diocese in the early 1970s.

The commission concluded that Pell knew — or was concerned about or alerted to — potential child abuse by Ridsdale, Monsignor John Day and Brother Ted Dowlan.

“We are satisfied that in 1973 Father Pell turned his mind to the prudence of Ridsdale taking boys on overnight camps,’’ the commission stated.

“The most likely reason for this, as Cardinal Pell acknowledged, was the possibility that if a priest was one on one with a child then they could sexually abuse a child or at least provoke gossip about such a prospect.

“By this time, child sexual abuse was on his radar, in relation to not only Monsignor Day but also Ridsdale.’’

We know via the report, and through Pell’s evidence, that Pell was made aware of offending or poor behaviour at St Patrick’s College, his alma mater.

St Patrick’s was the Ballarat school of choice for any Catholic parent across western Victoria who could afford it.

Many of its children, all boys, suffered terribly at the hands of several staff, the commission’s reporting on the school being a truly depressing account of sexual brutality and leadership failure.

Pell’s knowledge of offending in the 1970s, as the commission found, fits the view of the survivor groups that the cardinal must have known, or at least must have heard stories and rumours of the offending in the diocese.

Some of Pell’s own evidence supports this.

In the commission’s mind it is clear that Pell, in 1982, knew about Ridsdale being an abuser, and was there as a consultor when Ridsdale was punted to Sydney because of his abuse.

Pell himself utterly rejects the commission’s position and supporters find it bemusing that it effectively sided with the widely discredited bishop of Ballarat, the late Ronald Mulkearns.

The commission found on Ridsdale: “Cardinal Pell’s evidence that ‘paedophilia was not mentioned’ and that the ‘true’ reason was not given is not accepted.

“It is implausible … that Bishop Mulkearns did not inform those at the meeting of at least complaints of sexual abuse of children having been made.’’

It is important to remember, in this context, that the late Mulkearns was the driver of all the official Catholic secrecy and duplicity over offenders in Ballarat between 1971 and 1997.

Pell was relatively junior. He was not a decision-maker.

Mulkearns was the cover-up king, shredding documents and moving abusers. Victoria Police was complicit or asleep. Often both.

In many ways, Ridsdale was Mulkearns’s coronavirus, spread across the plains and valleys of western Victoria.

No one has ever accused Pell of this level of corporate bastardry. Although Mulkearns, as much as we can tell, was not accused by a large number of people of sexually interfering with children.

It is clear from the report, and from Pell’s own evidence, that Pell knew about offending in the Ballarat diocese for decades and that a sensible observer at the 1982 consultors’ meeting might have been suspicious about why the jolly (but evil) Father Gerry was on the move again.

But those familiar with church practice also argue that the consultors had no effective power, that the authority to move priests was with the bishop, and the priests on the body had less weight than a rubber stamp.

“This is deja vu. The cathedral all over again. They just don’t understand church practices,’’ one observer told The Weekend Australian.

Pell conceded in his evidence that he had the opportunity to follow up on a complaint regarding Dowlan but didn’t push it to its logical conclusion: to the headmaster at St Patrick’s or to his bishop, Mulkearns.

The commission report noted: “Cardinal Pell told us that, with hindsight, he should have done more.’’

What an awful oversight.

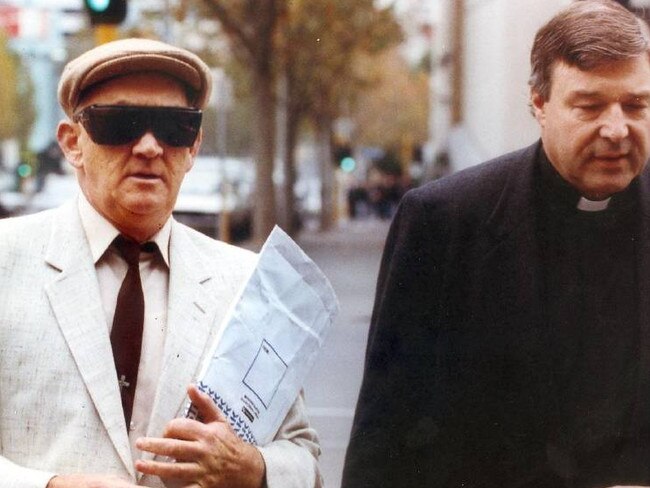

Based on the royal commission, what we now know about Pell is that in the 1970s, right through to the day he walked into court with Ridsdale in 1993 as a very public supporter, the cardinal was prone to grave lapses of judgment.

Another observer notes that Pell’s support in court for Ridsdale appeared to be a reflection of the bedrock of Catholicism — forgiveness and redemption.

While Pell today concedes the error of his ways on that court appearance with Ridsdale, this act more than anything explains why many in the Ballarat diocese are so deeply suspicious of his behaviour.

Critics argue that Pell’s support for Ridsdale in 1993 was not so much an act of compassion for a fallen brother but an act of profound arrogance.

By 1993 Pell was entrenched in Melbourne and on the Vatican radar, having landed in Bleak City in 1984 as an auxiliary bishop to Sir Frank Little.

At the time, Little was wearing himself out covering up abuse that had occurred in the archdiocese.

Pell’s rise through the ranks did not happen by mistake.

He is considered seriously bright, a hard worker, charismatic and loyal to his friends.

Yet in some ways you could argue the commission’s commentary on his years in Melbourne before becoming archbishop are the most significant.

Although being an auxiliary bishop is seen by some in the church as like being a well-dressed water boy for the archbishop, Pell had more power in Melbourne than he ever had in Ballarat.

The finding that his evidence on the handling of the priestly weirdo, Peter Searson, was implausible would be of some concern to the Vatican, given Pell’s then position, but none of the commission commentary refers to any of the abuse allegations against Pell.

But we also know that Pell and Little did not always get on so, in a practical sense, the cardinal may have been somewhat isolated within the then power structure.

One observer compared the relationship between Pell and Little to that of former prime ministers Tony Abbott and his successor, Malcolm Turnbull. “They just didn’t get on,’’ the observer said.

Some of Pell’s closest supporters are deeply frustrated with the way they believe the royal commission has “gone after’’ the cardinal.

But looking at the cardinal’s plight objectively, it does not look like we have a re-run of the botched cathedral allegations.

More a contested account of how George Pell turned a blind eye to some child sex offenders.

Based on today’s standards, Pell’s position was utterly unacceptable.