Calls for compromise amid fears Tasmania can’t meet AFL’s Hobart stadium demands

Tasmania’s snaffling of an AFL team was meant to be a glorious moment of statewide unity, so why is a state that has begged so long for this moment not dancing in the streets?

Tasmania’s snaffling of an AFL team was meant to be a glorious moment of statewide unity, a joyous affirmation of the island’s place in national sporting life after a decades-long struggle.

Instead, the deal finally granting the state the Australian Football League’s 19th licence is pitting Tasmanian against Tasmanian, and threatens to topple the nation’s last Liberal government.

So why is a state that has begged, barracked and badgered so long for this moment not dancing in the streets?

Almost all Tasmanians want the team and can’t wait until 2028, when they can don their retro-style team jerseys and sing the team song until hoarse.

The problem is the price tag. In exchange for finally letting the little kid play in its big league, the AFL has extracted the promise of a new stadium. But not just any stadium: a fully roofed, 23,000-seat colosseum to be built at a likely cost of more than $1bn (although the government is clinging to a $715m guesstimate).

That cost – for a state already deep in the red and failing to get on top of crises in public health, transport and housing – is simply too much for many. These include two Liberal MPs who quit the party to sit as independents, largely in protest against the stadium, throwing the Rockliff government into a precarious minority.

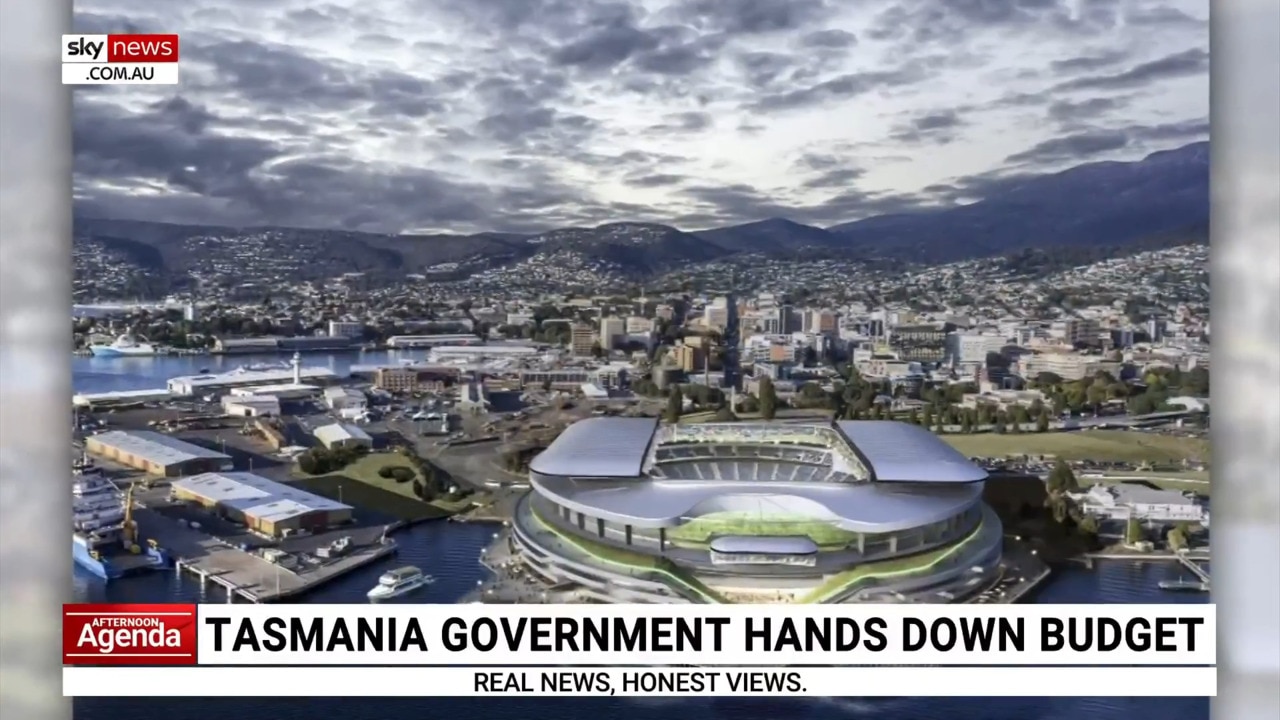

The AFL also has picked for the stadium site Macquarie Point: former industrial land adjacent to the Hobart waterfront that was earmarked for a housing, science, recreation and Aboriginal reconciliation precinct.

A 134-page contract signed by Premier Jeremy Rockliff and AFL chief executive Gillon McLachlan also commits state taxpayers to $60m to kickstart the team and build a training centre, as well $12m a year for team operations.

In return, the AFL guarantees 11 home games for the Tassie team – including seven at the new stadium – as well as $90m for game development and community football and $33m for talent pathways.

The deal includes deadlines for progress on the stadium and penalties of $4.5m a year on the state for failure to meet them, as well as ultimately giving the AFL the right to rip up the licence if its conditions are not met.

Even some of the most prominent backers of the stadium proposal believe the AFL has pushed the state too far and needs to rethink its approach.

“The AFL have been a bit tough there,” says Errol Stewart, a prominent Tasmanian businessman, hotel developer and member of the government’s AFL Taskforce.

“There’s no point the AFL fining the government or the team because you’re 10 minutes late or you haven’t got there (in terms of deadlines). I think that’s idiotic … given the enormous investment in this.”

There are increasing doubts – in the community, parliament and even parts of government – that Tasmania can meet the first major hurdle under the contract without changes.

By June 30, 2025 – 21 months away – the government has to:

● Design the stadium project on a difficult site beset by space, contamination and foundation stability problems.

• Wrestle the plan through an independent Tasmanian Planning Commission process that will address a host of significant heritage, visual impact and community concerns.

● Persuade a hostile parliament to approve the stadium in the form the AFL demands, potentially in conflict with changes the planning body recommends.

“I think it is mission impossible – or very close to it,” says Lara Alexander, one of the two Liberal MPs who quit in disgust at the stadium plan. “You cannot conclude in advance what the commission’s findings are going to be. What should happen now is that the government and Premier reveal plan B. They are sitting like deer in the headlights, saying: ‘We’ll deal with it when it happens.’ ”

The other Liberal MP who quit partly over the stadium, John Tucker, says the AFL faces “an awful lot of pressure” to strike a compromise should the government fail to get its preferred stadium through the planning commission and parliament.

“I would be hoping that’s what the AFL would do,” Tucker says. “I’d like to see the deal renegotiated. It’s very heavily weighted towards the AFL and not Tasmania.”

Some supporters of the stadium are also urging the AFL to renegotiate the stadium deal if the planning commission, site practicalities or parliament force changes or blowout timelines.

“It might have to be redesigned a tad here and there – you do that in just about every building project when you have to make changes to get compliance,” Stewart says.

A firm believer in the need for and benefits of a new stadium in Hobart, Stewart nevertheless cautions the AFL and government against forcing through a project without respecting “due process”.

“You can’t bulldoze the thing through,” he argues. “The (Gunns Ltd) pulp mill was a classic case of what happens when you try to bulldoze. People get the shits.”

Another key to public support will be the final dollar figures. Few believe $715m will cut it, once detailed design and planning have been undertaken, with opponents predicting $1.3bn to $1.5bn.

That would leave taxpayers further in the lurch. Currently, the $715m is in theory allocated: $375m pledged by the state government, $240m from the federal government, $85m from borrowings against land deals on the site and $15m from the AFL.

However, the federal contribution is not just for the stadium. The Albanese government defied advice from its state Labor colleagues to back the stadium, but has insisted Macquarie Point be more than just a sporting hub.

It appears the $240m in federal funds can be spent entirely on the stadium – but only if the state finds funds elsewhere for a broader “precinct plan” for the site.

“It (the $240m) is subject to an agreement under which the Tasmanian government will develop a precinct plan for Macquarie Point, including a focus on transport connections and housing … as well as wharf upgrades,” federal Infrastructure Minister Catherine King says.

According to some architects and urban designers, this is another “mission impossible”.

Shamus Mulcahy, an architect who worked on the London Olympic Village, says the stadium dimensions simply do not fit the site, much less leave room for transport hubs or housing. “It’s just never going to fit,” Mulcahy says. “No way. The whole thing is an urban design nightmare.”

He says the government will need a “land grab” over parts of Evans Street, which backs on to convict-built warehouses along Hunter Street, the wharf or Cenotaph Hill. Instead, he urges the AFL and the government to play games at existing stadiums at Bellerive, on Hobart’s eastern shore, and York Park, in Launceston, until an alternative site is found for the new stadium. “I love footy but I just think we can still have our team and still have a great stadium close to the city – just not at this spot,” Mulcahy says.

Returned Services League chief executive John Hardy says his members support the team and a stadium but oppose the choice of site, believing it would have a major detrimental impact on the neighbouring Cenotaph.

“It’s the oldest cenotaph in Australia and sits on a point of land that can be seen from the sea and that was the last thing that the first Anzacs saw when they sailed off to war,” Hardy says.

The government estimates the stadium will be 40m high, 240m long and 210m wide, not including additional concourse area.

Hardy says most fixed roof stadiums are closer to 54m high, while the stadium wall would be within 110m of the Cenotaph.

“It will dominate the Cenotaph,” he says. “It will have a huge effect on the Cenotaph. We are talking about a sacred site for some.

“Think of the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne or the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Canberra. I’m not sure that either of those two locations would accept something of this magnitude so close.”

Inquirer has confirmed there is consideration within government of dumping the stadium roof to lower the height and cost. But this would risk breaching the AFL deal.

The AFL did not answer questions about how it would approach an inability by Tasmania to deliver on any of its contract commitments, or its willingness to compromise. However, a spokesman said the roof remained a requirement.

Tasmania’s Labor opposition claimed this week any construction on the site would hit water at a depth of just 2.5m, while part of the site was “highly” contaminated and bedrock was as far as 20m down.

Such challenges could blow out, or even blow up, the project.

Some question the need for a new stadium at all, arguing Bellerive and York Park, the latter already being significantly upgraded, are sufficient.

“There is no need for a stadium at Macquarie Point,” says Roland Browne, of anti-stadium group Our Place. “Macquarie Point ought be a place for the community, housing, reconciliation and more. The government should not have let the AFL bully them into this arrangement. Plan B is a Tasmanian team with no requirement to build a new stadium. It is a plan where the government negotiates a deal that will not squander up to $1.5bn.”

Supporters, though, argue only a new, top-notch stadium in the vibrant capital city will attract and retain the players and support staff needed for a successful team.

“Players are used to state -of-the-art facilities and we need to replicate that,” says Russell Hanson, a retired businessman who has authored a report estimating the stadium would generate a $2bn visitation spend across 20 years.

“It’s not just footy players but their partners. If you have unhappy players or unhappy partners they’ll just go back to Greater Western Sydney or Gold Coast and our success period will just go out the door.”

Stewart agrees, arguing a stadium in the heart of Hobart will be a “massive boost for tourism”; a shot in the arm not only for the capital but the regions, as mainlanders turn footy trips into longer stays.

The Launceston-based businessman says he will build a hotel in Hobart due to the extra demand, but only if the stadium goes ahead.

Other northerners are openly hostile to so much money and focus being showered on the south. In Hobart, opposition is focused on the loss of Macquarie Point for a grander vision, as well as the stadium cost and scale.

Alexander and Tucker – both from the north – believe the “silent majority” firmly oppose the stadium. They are tipping it to be a key issue at the coming state election, due in May 2025 – a month before the AFL’s stadium approval deadline – giving new meaning to the term political football.

Labor leader Rebecca White maintains her opposition to the current stadium deal but appears open to renegotiation.

“Given Tasmanian taxpayers will be footing the bill, the government needs to provide a lot more information before Tasmanians will be convinced this stadium can be delivered for a price that’s fair,” White says.

“I would expect Tasmania can sit down with the AFL and have civilised, mature conversations about the best way forward.”

Rockliff concedes the full “costs and benefits of the project” are still being assessed but insists “fluctuations in construction costs” are factored into the $715m.

He dismisses suggestions the money should instead be spent on basic public services. “We are investing $12bn into health over the forward estimates,” he argues.

Rockliff insists the precinct plan, to be released next month, will include “early work” on transport connections, port upgrades and affordable housing.

Tasmanians, he argues, should get behind the stadium and wider plan. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Tasmania,” he says.

“A strong economy, fuelled by transformational infrastructure projects, enables us to invest in essential services such as health, housing, and education.

“It means jobs. It means a prosperous future for our state.

“It’s about aspiration and creating opportunity.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout