Business as usual on China will ruin us

If we ignore strategic and economic challenges posed by China, Australia will be a backwater state within a decade.

Australia is confronted by three big changes in our strategic circumstances that are making our steady-as-you-go approaches to security and economic development untenable.

We face a markedly increased risk of war in the Indo-Pacific; the global economy is restructuring rapidly in adverse ways; and the Australian economy has stalled with essentially zero productivity growth, declining international competitiveness and a flight of much-needed investment.

If we ignore these fundamental changes in our circumstances we will see Australia reduced to a weak and vulnerable backwater state within a decade. We urgently need to recalibrate, develop a new vision for our future and launch serious reforms.

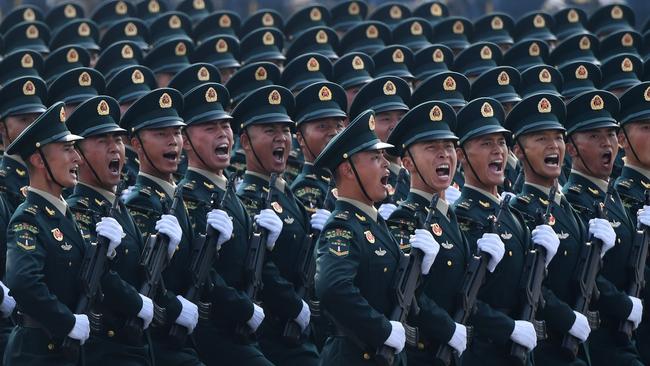

The most obvious strategic challenge is posed by China’s extensive preparations for war and the regime’s aggressive international behaviour. President Xi Jinping sees the tides of history flowing China’s way and he makes no secret of his intention to exploit them.

“The world is facing great changes unseen in a century … which brings great opportunities for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation … The great struggle, great project, great cause and great dream of our party are in full swing,” he has said.

At the core of this campaign, Xi repeatedly has stated his determination to seize the vibrant democracy of Taiwan: “Complete reunification of the motherland must be fulfilled and definitely will be fulfilled.”

China rapidly has expanded its military capabilities so it has by far the largest army, navy, air force and theatre ballistic and cruise missile forces in the Western Pacific. The junior general who led Taiwan contingency planning until late 2022 is now one of Xi’s two most senior military advisers. And 15 of the 24 members of China’s politburo have Taiwan experience, leading some analysts to describe it as a war cabinet.

In recent years China’s budgets have often given security and defence a higher priority than economic development. Xi calls this “integrating national strategies and strategic capabilities” and building China’s “Fortress Economy”. This huge resource redirection is probably costing between 1 per cent and 2 per cent of GDP growth each year.

The Chinese military has been practising for an invasion of Taiwan. Full-scale replicas of key strategic buildings in Taipei have been built, including the presidential offices and the foreign ministry, so army units can rehearse their assault plans. Similarly, full-scale replicas of American and allied warships and bases have been built in China’s western deserts to serve as targets for medium and long-range missile tests.

During recent exercises Chinese ships and aircraft have penetrated close to Taiwan and appeared to rehearse the initial phases of a major invasion. Recently Xi visited a paratroop regiment whose primary mission is to “liberate Taiwan”. Xi ordered the troops to make “all-out efforts” to improve combat preparedness.

CIA director William Burns has told a congressional committee that Xi has ordered his military to be ready to conduct a major assault on Taiwan by 2027.

The Chinese military makes clear that it is not only targeting Taiwan but also strategic facilities in Japan, South Korea, The Philippines and many more distant targets. Indeed, the Chinese military even has released a video of a simulated air and missile strike on the US’s Andersen Air Force Base on Guam.

Several official Chinese documents, such as the 2013 edition of China’s Science of Military Strategy, describe China’s “crucial maritime space” as including all of the Western Pacific and most of the Indian Ocean, extending well south of Australia and New Zealand. In the event of war, Chinese forces plan to operate across all of these regions as well as in the space, cyber and subversion domains. In the meantime, Chinese military and paramilitary forces have seized most of the South China Sea, they are occupying maritime features that are well within the exclusive economic zone of The Philippines, and they are harassing the territorial defence forces of Japan, The Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam and others.

The US, Australia and many other allies and partners also are being subjected to ongoing cyber, influence, coercion, subversion and “disintegration” operations. These are designed to penetrate, divide, disrupt and weaken targeted societies and render them more vulnerable in the event of a crisis.

The risks posed by this situation are great. US President Joe Biden has been asked four times whether, if China attacks Taiwan, American forces would be committed to fight. On each occasion he stated without hesitation that they would. President-elect Donald Trump has yet to be asked the same question directly but he is reported to have stated in private conversations that deterrence of China is one of his highest priorities.

If China attacks Taiwan, it seems likely that US, Japanese and other allied forces would be involved from the outset. In those circumstances there can be little doubt that Australia’s interests, values and alliance obligations would see Australia also at war.

This raises important questions about why the federal government has not been honest with the Australian people about the risks of major war and taken serious steps to prepare our society and economy.

As things stand, we may have to deal with this huge challenge before the end of the decade with little advance preparation.

The second strategic challenge is the rapid restructuring of the global economy, driven by China dumping its vast manufacturing surpluses into global markets.

This, in turn, is triggering tariff and other emergency protective measures to be taken by the US, most of Europe, democratic Asia and increasing numbers of developing countries. The origins of this global economic crisis lie in the decision of the Clinton administration in the US to support China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001. At the time it was widely assumed that Beijing would abide by the WTO rules, its economic opening would lead to political liberalisation and China would become a “responsible international citizen”.

In joining the WTO, China promised to lower its tariffs, eliminate non-tariff barriers, protect the property rights of foreign investors and open its markets to American and other international producers. However, China kept very few of these promises. Instead, it heavily subsidised its own industries and used a wide range of other mercantilist practices to penetrate, and ultimately dominate, key foreign markets.

This has led to the widespread de-industrialisation of the US, Australia, Britain and most other developed economies. Entire industrial regions in the US and elsewhere have collapsed, and millions of people have lost their jobs. The strategic impact of this vast industrial transfer has been huge. In 2004, US manufacturing output was double that of China. But by 2020 Chinese manufacturing output was double that of the US. This industrial imbalance has grown worse during the past three years. When China’s economy failed to recover fully from the Covid disruptions, its housing sector contracted, consumption fell and many Chinese businesses stalled. This led Beijing to stimulate the economy in part by encouraging many manufacturers to continue expanding production capacity.

In several key product categories, including electric vehicles and solar panels, China has now built more production capacity than is needed to supply the entire globe. However, with domestic demand weak, the only way for many manufacturers to stay afloat has been to send their growing production surpluses into overseas markets at low prices.

This dumping of China’s manufacturing surpluses is considered intolerable by the US, most of Europe and many other countries. The tsunami of cheap Chinese products is destroying the strategic industries of many countries, undermining their economies and rendering them more vulnerable to any new economic or geo-strategic shocks.

Not surprisingly, a strong fightback is under way. Western investment into China is at its lowest level in 30 years. Many American and European companies are reducing their footprints in China and some are leaving entirely.

Tariff and other protective measures are proliferating. The US already has 50 per cent tariffs on Chinese semiconductors, solar cells and medical products. It also has 25 per cent tariffs on Chinese steel, aluminium and batteries, and 25-100 per cent tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles. Trump’s policy is to impose a 60 per cent tariff on all Chinese goods, with a possible 20 per cent additional tariff following.

Nearly all of Europe is introducing 27-48 per cent tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, and 20-48 per cent tariffs on Chinese steel and other metals are being considered. Canada has imposed a 100 per cent tariff on Chinese electric vehicles and India has imposed 15-125 per cent tariffs on Chinese vehicles. India also has announced 30 per cent tariffs on most Chinese foods.

A rising number of developing countries also have joined the push back. Indonesia has imposed 200 per cent tariffs on Chinese textiles and other light manufactured goods, Turkey has introduced a 40 per cent tariff on Chinese electrical vehicles, and Brazil and Chile have announced tariffs on Chinese steel products.

What this means is that the era of unrestricted, high-efficiency globalised trade is over and the world trading system is fragmenting into three camps or blocs.

The first and largest grouping is the advanced economies led by the US, Europe, democratic Asia and, increasingly, democratic states in other parts of the world. The second grouping comprises China, Russia, North Korea, Iran and several smaller authoritarian states. The third group is made up of the undecideds and neutrals.

The trade and financial separation between the first two blocs is growing rapidly. But much of the trade within each bloc is intensifying. This is particularly the case in the second bloc where trade between China, Russia and North Korea is surging.

Australia is currently in the undecided, neutral group. At the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation and G20 summits, Anthony Albanese championed “open, inclusive and rules-based trade”. This sounds fine in theory but it reeks of naivety when the US, Europe, India and many other countries are busily building trade barriers to protect themselves against China’s trade tsunami.

When Xi incongruously joined the Prime Minister in championing free trade, Albanese found himself in partnership with the leader of the Chinese Communist Party opposing the interests of the US, Europe and most other allies, and he also surrendered what remains of Australia’s manufacturing sector to the Chinese flood.

What is worse is the absence of an honest government discussion about the changes under way in the international economy and a realistic strategy for ensuring future prosperity and security.

The third strategic challenge is that Australia’s economy is in poor shape to compete in the rapidly changing international environment. Across recent decades, successive Australian governments have abandoned whole industries to win the benefits of globalised efficiencies and international supply chains. So while mining, energy, agriculture and some service industries have done well, most manufacturing has disappeared. In the late 1960s manufacturing accounted for 26 per cent of Australia’s economic output. It now accounts for 5 per cent.

In the past three decades public sector spending at the federal and state levels has ballooned with the consequential taxation, regulatory and other burdens on industry and the broader community seriously weakening Australia’s competitiveness. Australia’s multifactor productivity growth is effectively zero per cent and the country’s international competitiveness ranking has fallen to 19th place, well behind Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, and a very long way behind countries such as Ireland, The Netherlands and Denmark. Australia is no longer an attractive destination for foreign and even domestic investment. In recent years more investment has departed our shores than has arrived.

Unfortunately, many recent federal and state government policies have made this situation worse. Additional layers of red and green tape, surging electricity costs and falling electricity reliability, together with new constraints on industrial flexibility, have crippled many enterprises.

Especially important have been sector-wide industrial agreements, removal of the link between productivity improvements and wage determinations, same work, same pay regardless of worker experience, and related initiatives. In combination, these measures have made Australia a costlier and much less friendly place for business.

Perhaps worst of all has been the sovereign risk sprung by Queensland on several foreign corporations that have invested billions in developing gas, coal and other export operations, only to find the taxation levels increased markedly without consultation as soon as the operations started to return profits.

In this business-unfriendly environment it is not surprising that per capita GDP has fallen for the past six quarters, company bankruptcies have reached record levels and Australia’s international reputation has been seriously damaged.

There are three key things we need to do to turn this situation around. First, we need a season of honesty. The government must brief the nation properly on the serious challenges we now face. The media also needs to do a more professional job of analysing these issues.

Second, we need a vision for how Australia can achieve a new era of prosperity and security. Part of this vision should be a program for boosting our defences for the coming two to five years as well as for the longer term.

But the core of the vision should be a program to remake Australia into a great place to invest, to do business and to live. All Australians need to understand that if we are to enjoy sustained prosperity in the new environment we must quickly turn Australia into a highly preferred location for investments.

We need to focus primarily on attracting industries that build on Australia’s competitive advantages – such as our abundant mineral resources, traditionally cheap and reliable energy supplies, abundant land, skilled workforce and our relatively stable and predictable legal and political systems. Priorities should be investments in resource extraction and processing, and energy-heavy industries as well as some high-end design, technology and educational industries. Especially favoured should be the production of intermediate goods rather than highly complex manufactured products. Leading contenders should be processed metals and chemicals, pharmaceuticals, fertilisers and the production of a wide range of fabricated intermediate products – most intended for export.

China currently dominates most of these markets and many countries would welcome a highly competitive and fully trusted alternative supplier.

If we are to succeed, we need to reduce the costs and complexities of business operations. We need to cut corporate taxes to world-leading rates, reduce government overheads and simplify regulatory and industrial-relations frameworks. Major projects should be approved in weeks rather than decades.

Governments should not attempt to pick winners. They should focus instead on generating the favourable environments in which competitive international businesses can thrive. State governments should compete to attract the best investors.

Finally, we need to take a clear decision. If we continue on our current course of declining productivity, weakening industrial strength and falling standards of living, Australia soon will become a weak and vulnerable backwater state with very poor prospects.

Alternatively, if Australian governments inform the public about the serious challenges we face and lead a thoroughgoing process of economic and security reform, the way will be open for a new era of prosperity, international influence and security.

Ross Babbage is chief executive of Strategic Forum in Australia and a nonresident senior fellow at the Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments in Washington. His latest book is The Next Major War: Can the US and Its Allies Win Against China?

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout