Bushfires: why this fire season is so different

Nothing is typical any more: even the scientists are confused. Yet we’re learning from these infernos.

You need to know what happened at Wytaliba to understand why this bushfire season is so different and extraordinarily dangerous.

Parts of the country that are burning have never burned before: rainforests are going up and communities attuned to dealing with floods and cyclones are being confronted by walls of flame, hurling them into a whole new world of hurt and heartache.

READ MORE: Arsonists suspected in dozens of fires | Give funds to needy, GetUp told | Scientists ‘careful’ over weather signals | Empty dam leaves farmer distraught | As bushfire window shrinks, ‘we need to get more inventive’ | Bushfire blame game spreads | Focus on families, not politics | Libs challenged on ranger cuts | Homes’ chances up 25pc if owner fights | Lodge owner takes on flames, for now

Those who prepared painstakingly, as the 100-odd residents of Wytaliba did, discovered nothing could stand in the way of the firestorm that hit on Friday afternoon. In 15 terrifying minutes, a hot, hazy day on the NSW Northern Tablelands turned into a test of survival when the township was engulfed. Two died and at latest count 45 houses were destroyed.

Most people in Wytaliba had trained to fight fires. Founded as an alternative-lifestyle commune, the cluster of family homes carved out of a tangled eucalyptus forest, crisscrossed by earthen paths, had its own brigade. No matter.

“The intensity is what you can’t handle,” says Tony Keating, a resident of 35 years and member of the fire crew. “We’ve had a fire every second year for as long as I’ve been here and we’ve always been able to deal with it. But this time it was impossible … It came up like a bullet out of a gun.”

-

Scorched green land

Step back and consider the big picture. Southeast of Wytaliba, the picturesque rainforest at Terania Creek in Nightcap National Park is aflame near Lismore; behind Coffs Harbour, the towering, moss-lined Antarctic beech forests at Wauchope are burning; the rolling dairy country of the Clarence Valley has gone from emerald green to a scorched ebony in places, having received less than a tenth of its average annual rainfall; beloved Binna Burra Lodge in the Gold Coast hinterland was razed in September, something no visitor to that usually lush retreat backing on to World Heritage-listed Gondwana rainforest could have come at; suburbs back from the beach on the Sunshine Coast have been evacuated five times this year and counting, with homes lost to the advancing fire fronts.

“If you had told me that Binna Burra was going to burn down and that was just the pipe opener to the fire season, I would have said you were nuts,” says David Bowman, the professor of pyrogeography and fire science at the University of Tasmania. “But now we are seeing all these other iconic places like Wauchope (and) Nightcap Range burning and it’s so unbelievable. These are wet, subtropical or warm-temperate rainforests … I am trying to remain on an even keel. It’s so serious.”

More than one million hectares have been blackened in NSW — 2½ times the area affected on Black Saturday 2009 in Victoria — and Queensland has had more homes destroyed in the past 12 months than the accumulated losses from all past bushfire seasons. If scientists are agog, imagine the shock for the local communities and emergency services, which have been stretched to breaking point this week, as the fire conditions in NSW touched catastrophic levels on Tuesday and continue to deteriorate north of the border.

-

Parched soil

While the debate over who or what’s to blame rumbles on — green-minded councils and national park managers for failing to back-burn overgrown forests or federal and state governments for not acting on climate change — the focus on the ground is to preserve life and property. The undeniable fact is that years of drought, higher-than-average spring temperatures and low rainfall have turned vast tracts of country into a powder keg, waiting for the strike of a match or lightning to ignite.

As Ross Bradstock, director of the Centre for Environmental Risk Management of Bushfires at the University of Wollongong, explains: “What we are seeing in northern NSW and Queensland is exceptional dryness, compounded by rainfall deficit, temperature anomalies, continuous fuel loads across the landscape, winds and low humidity. Those are the fundamentals of major bushfires. What’s different is that the conditions have extended into areas that haven’t traditionally burned to the extent they now are.”

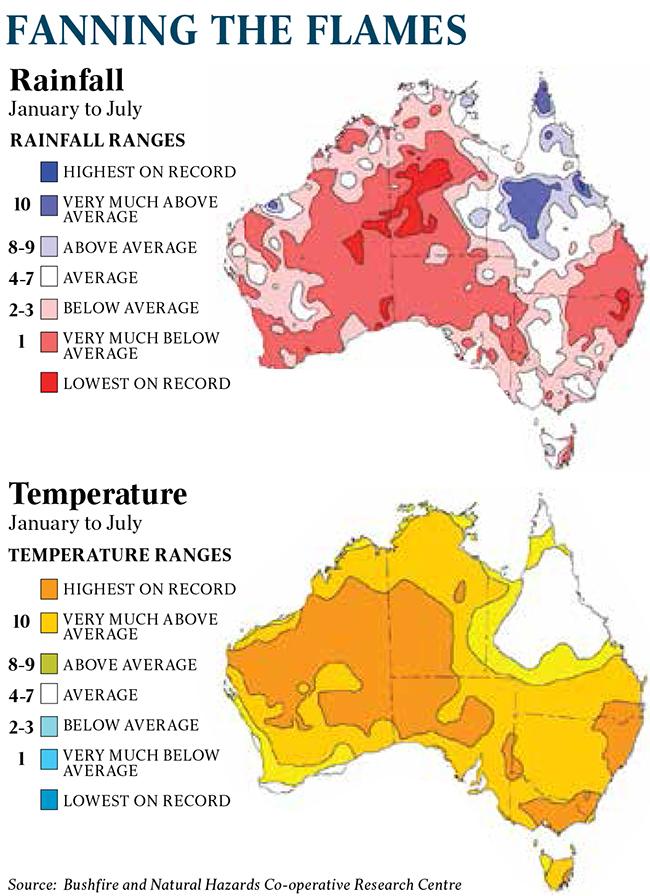

The seasonal bushfire outlook issued in August by the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Co-operative Research Centre quantified the problem. Drawing on the expertise of emergency services and agencies and top scientists, it found soil moisture in Queensland was in the lowest 1 per cent on record for areas from Rockhampton on the state’s central coast southward to the NSW border.

Much of central and northern NSW had experienced below-average winter rain, with some districts historically dry. “Widespread significant soil moisture deficit” had resulted in an early start to the fire season there.

Queensland had a taste of what was to come in November last year, when the state was ravaged by 140 bushfires that burned out more than a million hectares of countryside. Fifteen homes and 60 sheds were lost, prompting the Audit Office to review the emergency response.

The report, itself a follow-up to a highly critical 2014 review by the watchdog agency, makes uncomfortable reading in light of the drama now unfolding in central Queensland, on the Sunshine Coast and to the south and west of Brisbane.

Though it found that Queensland Fire and Emergency Services had improved its “visibility and oversight” of bushfire risk, including establishing the Office of Bushfire Mitigation and area fire management groups, QFES had missed deadlines to improve readiness for this taxing season. Further, it had not fully implemented any of the recommendations from the 2014 report, despite committing to do so within 12 months, and more work was needed to ensure communities were not exposed to higher levels of risk “than they need to be”.

Criticising QFES’s collaboration with other key stakeholders, the Queensland Audit Office said: “In particular, it should continue to engage with land managers and local governments to better identify bushfire risks and priorities mitigation activities.”

-

Tongues of 50m flames

No one is questioning the effort of the volunteer and full-time professional firefighters on the ground. The wonder in both Queensland and NSW is that more lives haven’t been lost, given the size and intensity of the fires.

Both victims in Wytaliba, grandmother Vivian Chaplain, 69, and fellow community elder George Nole, aged in his 80s, died trying to defend their homes. The resurgent Kangawalla fire to the west of the township, spotted as a plume of smoke about 3pm on Friday, came on so quickly that others barely had time to grab children and pets before fleeing.

The howling wind felt like it would “rip your head off”, one survivor recounted. At the height of the emergency, people found refuge on a cricket pitch, eyes watering in the heat and dense smoke as 50m tongues of flames licked at the outfield.

“It shows you … what a fine edge the environment is on,” says Keating. “A few degrees lift in temperature, a shift in weather patterns and, bang, we’re in trouble.”

The third victim, Julie Fletcher, 63, also died at her bushland home, in Johns River outside Taree on the NSW mid-north coast.

At the Scenic Rim, southwest of Brisbane, where new-built subdivisions around Boonah and rural homesteads are under ferocious threat, mayor Greg Christensen has never seen anything like it. “We’ve had fires run across the ground like it was a pool of kerosene,” he says. The strain is telling on weary fire crews, who barely had time to catch their breath when the severe fire conditions at the weekend relented, only to ramp up again on Wednesday.

Reinforcements from Tasmania, the Northern Territory and New Zealand have been welcomed with open arms: more hot and blustery days are forecast.

The question is: How long can the thin, red line hold?

Typically, the fire season in Queensland is over by December, but this year’s onslaught not only began sooner than ever but also threatens to extend into next year. Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk says relieving rain isn’t on the horizon before January at the earliest.

-

Danger signs

By then, Victoria will be in the frame if the east-coast drought persists, its wet eucalyptus forests drying out to unleash some of the world’s most potent fire fuel loads. Bowman is seeing danger signs in Tasmania, where destroyed rainforest accounts for an estimated 3.2 per cent of losses this year. In 2016, the famed pencil pines burned in the rainforest-like Gondwana reserves around Lake Mackenzie on the state’s Central Plateau, an ominous omen.

The author of a book on Australia’s rainforest estate, Bowman has ventured into what should be some of the state’s wettest forests to gauge the fire risk. “It’s a worry,” he says. “You put your hand on a log that should be slimy, and it’s dry and powdery … ready to burn.”

He is deeply “discombobulated” by what is happening in northern NSW and Queensland. For all the misery the fires are causing, scientists have much to learn from the novel sites that are burning.

“That is part of the materials we need for the adaptation step … I am very aware it is terrible at a human level but scientifically it is very significant,” Bowman tells The Australian.

“If we can start understanding the fire progression, how fires interact with different land uses and land types … we can start wrapping our minds around the fact that this type of country has burned.”

-

Risks underestimated

Bradstock, an expert consultant to the royal commission into Victoria’s 2009 Black Saturday disaster, says Queensland’s bushfire risk has been creeping up on the 100-point Forest Fire Danger Index. Traditionally, a bad fire day in the state’s thickly populated southeast scored about 50; but last November and during the current emergency it would have nudged the century mark at times.

That might be a far cry from the conditions on February 7, 2009, in Victoria, where the FFDI ranged from an unprecedented 160 to 200, ushering in the new “catastrophic” classification after 173 people died in the flames of Black Saturday, but it is highly confronting for communities with little or no bushfire exposure and would sternly challenge even the most hardened firefighters.

“We know from our research that people underestimate their own personal bushfire risk,” says Richard Thornton, chief executive of the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Co-operative Research Centre. “Our research is consistently showing that many Australians, particularly those in higher-risk areas, are not sufficiently ready for fire and have not put fire plans in place well ahead of time.

“They understand that when the conditions are right, hot and windy days, with dry vegetation, fires will occur. But they just don’t think it will happen to them.”

It’s no exaggeration to say Australia is entering uncharted territory this bushfire season. What’s evident from the experience in NSW and Queensland to date is that more of just about everything is needed to tackle the lethally dry conditions: more muscle power on the ground, more water-bombing aircraft overhead, more cash from the taxpayer.

“The risk is here, the risk is now, and we will have worsening conditions as we head into summer,” NSW Rural Fire Services Commissioner Shane Fitzsimmons warns. Who can afford to gainsay him?

Additional reporting: Craig Johnstone, Charlie Peel

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout