Bumbling and own goals leave Albanese on the back foot

Anthony Albanese has made a bad situation worse for Labor, with strategic mistakes, failures to address policy weaknesses and a distorting obsession with damaging the PM personally.

It is the Opposition Leader who is making the political and parliamentary mistakes, it is the ALP that is riven with division over climate change, and Labor’s outlook for the coming year is one of diminished leadership and declining voter support.

In January, it was Scott Morrison’s leadership under public pressure because of the response to bushfires and the Prime Minister’s holiday in Hawaii. The Coalition also was feeling the heat of global warming, and support was slipping away after the miracle election win six months before.

The COVID-19 pandemic and Morrison’s health and economic responses to it changed public attitudes to him and are fundamental to Labor’s role reversal, but they are not the whole reason. Albanese has made a bad situation worse for Labor, with tactical and strategic mistakes, a failure to address fundamental political and policy weaknesses, a distorting obsession with damaging the Prime Minister’s personal standing and a self-destructive use of negative one-line barbs that have backfired.

The resignation this week from the opposition frontbench of Joel Fitzgibbon as agriculture and resources spokesman because of climate change policy crystallises the turnaround for Labor and highlights the discontent within the party’s ranks.

Fitzgibbon has campaigned since the election loss last year to get Labor to pay more attention to the job fears of its traditional base of blue-collar workers in rural and regional areas than to the global warming concerns of the inner city. The party veteran declared that Labor had spent too much time talking about climate change and taking an uncosted carbon emissions reduction target of 45 per cent to the election last year, and “not enough on issues important to our traditional base”.

The decline in the Labor vote at elections since Kevin Rudd’s victory, especially in regional areas, bears out Fitzgibbon’s fears. In 2007, Labor held 24 rural or regional seats, of which eight were won on more than 50 per cent of the primary vote. In the metropolitan progressive belt, the ALP won 10 seats, including four with a primary vote of more than 40 per cent.

Compared with the election result last year — real election results, not polling — Labor’s primary vote has gone down 10 per cent and it has lost nine of the regional seats it held in 2007 and three in the progressive belt.

Labor has no rural or regional seat in Queensland, Western Australia or South Australia, and Fitzgibbon’s own seat of Hunter in NSW, a Labor stronghold for more than 100 years, was pushed to preferences, with Fitzgibbon surviving only on preferences. Labor has gone backwards since 2007 and the biggest losses have been in rural and regional areas, particularly Queensland.

For Labor frontbenchers to claim Fitzgibbon is out of step with Labor voters, that he has only a “handful of support” and is being self-indulgent, is to ignore the brutal facts of Labor’s continuing demise and that voters have rejected Labor’s climate change and tax policies at the past three elections.

Yet Albanese is still incapable of producing a solid climate change policy beyond a 30-year, uncosted aim for Australia to have net-zero emissions in 2050 and keeps Mark Butler, the architect of those policies, in place while leaving Fitzgibbon bereft of support.

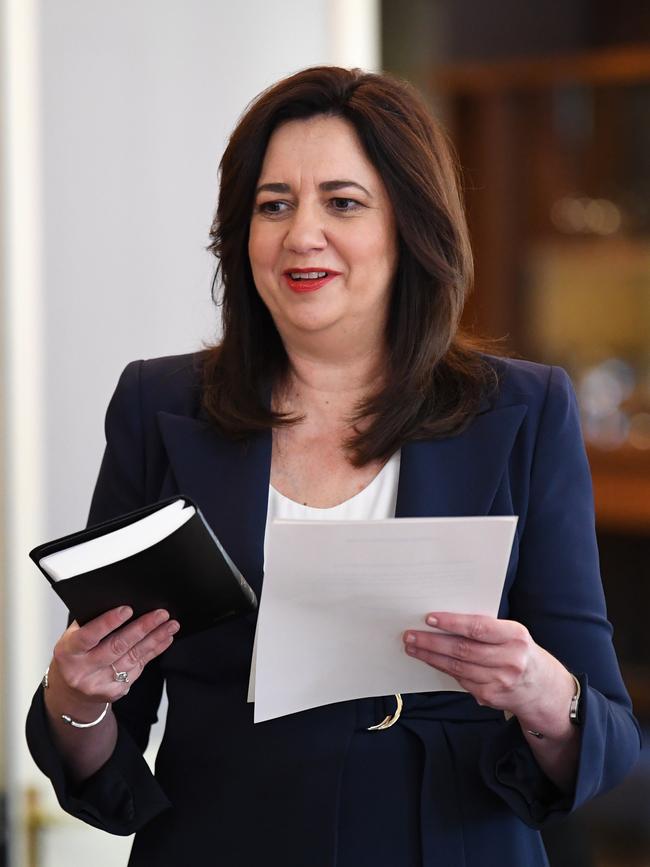

There is also a continuing public display of self-delusion from senior members of the parliamentary Labor Party who naively or deliberately misread events, such as Annastacia Palaszczuk’s state Labor victory in Queensland or Democrat Joe Biden’s US presidential win, to deny or dissemble about Labor’s almost terminal decline in voter support and continuing electoral losses.

Just in the past two weeks the Opposition Leader has rallied his troops with the observation that people are prepared to “vote Labor” in Queensland and that Biden’s victory in the US was justification for a radical climate change agenda, which includes net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, phasing out oil, banning fracking and dumping coal for renewables.

These election victories, and to a lesser extent the ACT Labor-Green re-election, were hailed by Albanese as signs of hope for federal Labor in Queensland, a justification for a more radical climate change policy and the isolation of the “Trump-friendly” Morrison, who he said played partisan politics during the US election.

Yet Albanese seems to forget that Queensland Labor leader Peter Beattie and federal Liberal leader John Howard were exact leadership contemporaries from 1996 to 2007 and premier and prime minister together from 1998 to 2007 — that is, nine years when Queenslanders voted strongly for the ALP at state level and as strongly for the Coalition at a federal level.

And Palaszczuk’s victory was for a Labor premier who provided the state government go-ahead for the Adani coalmine after Bill Shorten’s defeat last year and who campaigned as an incumbent government that successfully handled the COVID-19 pandemic. Queensland Labor’s most radical MP, Jackie Trad, lost her seat after being pushed out of the ministry.

As for Biden’s victory, it was based on an anti-Trump vote from historically high numbers of Democrat voters during an obvious failure of health leadership against coronavirus. The Democrats had the hardest fights in areas such as Texas, Pennsylvania and Alaska, where oil and mining are so important.

But the growing disappointment and disillusion in Labor ranks is not just a result of the decade-long wrench between the inner city and the regional and outer metropolitan but also about parliamentary and policy strategies. Revelling in the hit Morrison had sustained over bushfire management, Labor was slow to appreciate the seriousness of the coronavirus threat and allowed Morrison a head start that only added to his authority.

Albanese ridiculed the Coalition for mixed messages and argued that health be given the first priority. He also belittled the establishment of the national cabinet of all federal, state and territory leaders that now has formally replaced the Council of Australian Governments.

Yes, it’s hard for an opposition to make an impact, and incumbency is a great asset during a time of global health emergency and recession, but oppositions need to appear as positive as possible and not overreach in their political desperation to get attention.

There are three recent examples where Albanese made errors that detracted from Labor’s credibility on economic management, pandemic control and foreign policy. Always looking for a one-line put-down, Albanese brought out the term the “Morrison recession” as the Australian economy tanked. He tried it a couple of times, then introduced it into every possible parliamentary question he could. It was a mistake.

No one blamed Morrison for the global recession. It gave the Coalition the chance to introduce the more credible “COVID-19 recession”, and Morrison turned the line against Labor, saying that “if they don’t know what caused the recession they won’t know how to get out of it”. A silly one-liner turned into a telling attack on Labor’s economic credibility.

After coronavirus infections began to come under control in Victoria Albanese, who had refused to criticise Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews after the failure of the state’s hotel quarantine scheme and more than 800 deaths, decided to try to trap and embarrass Morrison and Melbourne-based Josh Frydenberg with a parliamentary motion congratulating Victorians on their success.

But it was Albanese and his Geelong-based deputy, Richard Marles, who got trapped. Morrison allowed the motion and the Labor leaders both fell short on time and blocked any chance of Victorian MPs who had been under the stage four lockdowns — unlike Albanese and Marles — speaking in parliament.

The Prime Minister and the Treasurer responded with sensible and robust speeches that used all their time and left Labor in the shade.

That mistake caused angst within Labor ranks beyond all proportion to the parliamentary tactic.

Then, pursuing another one-liner that Morrison was close to Donald Trump and partisan in US politics, Albanese formally called on Morrison to “contact” the US President and urge him to “respect the democratic process”. He repeated his call at a press conference, and NSW supporters declared he was “absolutely right” to tell Morrison to pick up the phone.

It was so puerile that there was a genuine sense of embarrassment as Albanese tried to walk away from another nasty one-liner that had blown up in his face and undermined his credentials, and those of Penny Wong, as a mature person able to deal with the world stage.

It has been a tough year for Albanese and every other opposition leader but the advantage of incumbency is recognised and allowed for. What’s not forgiven is Albanese’s self-induced damage and mistakes making it easier for the government to demonstrate it’s in control.

The remaining two weeks of parliament this year could get even tougher for Albanese and there’s no guarantee next year, full of uncertainty and still potentially an election year, will be any better.

As parliament prepares for its last sitting before the long summer break, Anthony Albanese and Labor find themselves in the opposite position they were in at the beginning of the year.