Budget 2022: Treasurer vows to keep a tight lid on spending

Now is the time for restraint and resilience as the world prepares for a third great global economic downturn in the space of just 15 years.

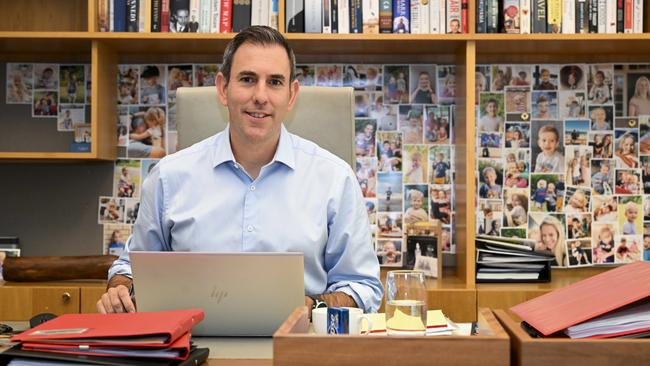

Jim Chalmers’ message to Australians on Tuesday night will be blunt in its delivery and sobering in substance. Now is the time for restraint and resilience as the world prepares for a third great global economic downturn in the space of just 15 years.

Inflation will remain higher for longer, unemployment will rise and the budget is heading toward a crunch point with an unsustainable structural spending curve into the future.

Chalmers was a young Labor staffer when Kevin Rudd brazenly declared in 2007 that the Howard government’s pre-election “reckless spending must stop”.

When he became an adviser to treasurer Wayne Swan after Rudd was elected, Chalmers was charged with helping deliver Labor’s new doctrine of fiscal conservatism.

It didn’t last long. The fight against inflation lasted barely months. When the global financial crisis hit, the budget surpluses Labor had inherited were quickly turned into deficits and the debt-free status achieved under Howard and Costello was erased.

Now as Treasurer, the 44-year-old is faced with challenges not dissimilar to those of 15 years ago when Labor previously returned to office after 11 years of Coalition government – rising inflation and rising interest rates in a strong pre-GFC economy.

The policy prescriptions and economic narrative Labor is now offering also have echoes of the past. Investment in skills and training, infrastructure, reforms in health and aged care – spending couched as productive investment that won’t add to the inflation problem.

Chalmers agrees that some of those problems were analogous to the new dilemma he now alone must tackle as Treasurer.

But he rightly argues the economic environment is underwritten by a fundamentally different crisis when the first of the three great economic declines of the new millennium hit. “There were a couple of key differences; yes inflation was a feature of the economy in 2007 like it is in 2022, but that inflation challenge gave way pretty quickly to the GFC,” says Chalmers in an interview with Inquirer.

“If you think about the historical sweep here, we are basically at risk of a third big global downturn in a decade and a half.

“The first one, the Global Financial Crisis, became an issue for demand. The second one was a pandemic crisis which became an issue for supply chains.

“This time it’s really different because it’s a global inflation problem which is causing blunt and brutal interest rate hikes around the world, and the risk is a hard landing in some of the big economies. This is a very, very different beast.”

Economist Chris Richardson says the one thing in common is the need to fight a crisis and that Chalmers’ background, as a witness and participant, gives him the experience needed to fight the next one.

“He comes to the job with a lot of experience under his belt,” says Richardson.

“One thing that is common is the need for crisis fighting, but the circumstances that a Treasurer faces now tend to be more volatile these days. There are geopolitics, world politics, new technologies – the volatility of conditions is higher than it used to be.

“I don’t think Australia is good at handing chronic problems but we are good at handling crises well.”

Chalmers’ first budget now presents a clash between fiscal repair, the coming economic shock, a cost-of-living crisis, and Labor’s policy ambitions.

Framing the politics is Labor’s charge that it inherited a debt crisis from the Coalition’s pandemic response and a fiscal position that, while vastly improved on where it was just a year ago, is still in need of repair.

It is the first budget for Labor in almost a decade. The spending pressures on the Treasurer from colleagues who are eager to satisfy promises to their constituencies and bankroll a new social agenda is obvious.

Yet the economic message is demonstrably pessimistic from Chalmers. The Treasurer’s outlook is grim: inflation remains determinedly high, upward pressure on interest rates persists; and Australia – while in a stronger position than its peers – won’t be spared from the shocks of a global downturn.

There is a fine line between being honest and talking the economy down. Chalmers is working on the basis, however, that while the macro-economic conditions may be different, the impact on people’s livelihoods isn’t. This is deliberate. Chalmers is also speaking to competing audiences. On one hand he is talking up the scale of the emerging post-pandemic global economic crisis to apportion blame for a fall in living standards to global factors. On the other, he is trying to send a message to his ministers and the caucus that there is no bucket of cash to splash around.

After 10 years of unresolved ambition, newly minted Labor ministers now have the keys to the till and want to spend. Assuming there is a solid basis to what Chalmers is saying – which evidence suggests there is – he will have to rein them in. This is the intriguing political element to the budget.

Is Chalmers speaking for the whole of the government in his messaging, or there is an internal contest over budget orthodoxy under way?

If Chalmers succeeds, Anthony Albanese will reap the political rewards. But as the leadership heir apparent and the front man for the government’s economic agenda, Chalmers will wear the consequences of Labor’s failure to meet the expectations it has set.

The internal challenge for Chalmers is to curb the natural inclination of Labor to spend. The budget will reveal whether he has won this argument.

“The types of challenges we are dealing with were understood before the election because inflation had already spiked before the election, interest rates were rising, electricity prices were already threatening,” Chalmers says.

“So these areas we are working through are familiar but the pressures have intensified.

“Even since the July statement that I gave to parliament, the global situation has got more challenging, inflation has become more persistent and the composition of inflation is different, natural disasters are going to push up inflation, energy prices are pushing up inflation.

“Overall, we anticipated the pressure on the budget and the economy but those pressures have intensified faster than the economists were expecting at the start of the year.”

The internal politics of austerity become difficult when the budget will confirm a much stronger fiscal position than expected. The post-pandemic recovery over the past 12 months has been remarkable.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor suggests the budget based on monthly statements from October 2021 to June 2022 shows it is now effectively back in surplus.

That might be a stretch too far but nevertheless it will be close, and largely a product of forces beyond either the Albanese government or former government’s input – with strong commodity prices and higher income tax receipts from the jobs recovery driving the revenue gains.

The outcome for last financial year showed a deficit as share of the economy better than the 20-year average – a remarkable turnaround from where it was 18 months ago.

The new Treasurer is now stuck between a rock and a hard place. There will be extra revenue in the budget because of commodity prices and personal income tax receipts. Bracket creep, as a product of inflation and higher wages, will be evident over the forward estimates.

In that sense, inflation is good for the budget but bad for the economy.

There will be good news in the budget which Chalmers will want to take credit for. Yet the revenue increases also serve to undermine the argument that Labor was bestowed a fiscal disaster.

The stacks of money, estimated by Deloitte Access Economics to be up to $114bn in additional revenue over the forward estimates compared to the forecasts in the March 2022 budget, will also provide a disincentive to rein in the spending.

As Deloitte also points out, spending will also be significantly up. The kite-flying over the potential abolition of the stage three tax cuts would have also been harder to justify considering the better bottom line news for the budget over the short term.

Richardson sums it up as a good problem to have. Even if it doesn’t fit the political narrative.

“Broadly, although a lot of the news around the budget is bad for the economy, it’s not necessarily bad for the budget,” he says. “The major difference is inflation … if you are a wage earner, your living standards go backwards … that’s where the political action is. It’s bad for the economy more generally. But it’s good for the budget … inflation adds to the tax take.”

Richardson says the debt-to-income ratio will come in under the previously forecast 33.1 per cent in 2025-26, pointing to the old adage that inflation helped economies pay down debt following wars.

Chalmers is right, however, that it is temporary, admitting that the structural spending dilemma will have to be addressed if not in this budget then the next and those following.

“The best way to understand the budget is in two halves,” he says. “In the near term, we have very welcome and very substantial improvements to revenue bolstering the budget over the course of the next year or two. But because that goes nowhere near making up for the big structural pressures in the budget, it means the budget deteriorates over time.”

So far, Chalmers has not outlined how he intends to tackle the cost blowouts in the NDIS, the growing social welfare bill, the pressures in aged care, health and defence spend. There will be action around the edges but anything substantive looks like it will be kicked into next year and beyond. There is now little doubt that, eventually, Labor will trim back the stage three tax cuts that are due to come into effect in 2024.

“We are encouraging people to see this as the first of three or maybe four budgets in this parliamentary term,” Chalmers says. “This budget will begin the long hard road to budget repair before we arrive at the final destination. When you are dealing with challenges of this magnitude you need to start somewhere, so we are starting with spending restraint, winding back waste, some multinational tax reform and making sure the targeted investments (election spending commitments) we make are defensible in terms of bang for buck. So when you get big upgrades in revenue you take a more responsible approach to banking them.

“The backdrop to the budget is natural disasters, rising inflation, global deterioration and big persistent structural spending pressures. The best response to that combination is restraint in the budget and resilience in the economy. That will be the overwhelming takeout of the budget on Tuesday night.”

Taylor, unsurprisingly, is sceptical that Chalmers will make the hard decisions on spending that need to be taken. As are some economists. The revenue gains provide a political disincentive for the Albanese government to rein in the spending decisions.

Chalmers claims he is confident, however, that the spending commitments in the budget – including an as yet unspecified cost-of-living response beyond those already announced – will in no way impact monetary decisions of the Reserve Bank.

He admits he has been in discussions with Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe about what the government is planning in the budget to ensure it aligns with the central bank’s task of bringing down inflation. The pair spent two and a half days together in Washington DC last week at the meetings of the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors.

Chalmers says the relationship is strong. But it is also fraught. The economic pain that Lowe has inflicted on mortgage holders through punishing rate hikes in his mission to return inflation to the 2-3 per cent band will ultimately translate into a proportionate electoral pain inflicted on the government.

At the same time, the monetary policy environment leaves Chalmers little wriggle room in the budget to address the cost-of-living pressures faced by ordinary Australians.

“Obviously not to go into detail, but I have a very productive working relationship with Phil Lowe. I understand what he is trying to do and he understands what I am trying to do,” says Chalmers.

“The key takeout from those discussions is the best thing government can do in budgets is not to make the task of central banks harder and not make inflation worse than it would otherwise be.

“We don’t criticise the domestic policies of other countries but it’s clear to everyone around the world that if you don’t get it perfectly right, as we have seen in the UK, it has consequences. We are all very conscious of that.

“I’m confident that in this budget I have things nicely lined up so that we are responding to what is the primary influence on the budget, which is inflation.”

The credibility of Labor’s revived claim to sound economic management hinges on Chalmers’ ability to deliver action in the budget that matches the pre-budget rhetoric. Real and demonstrable spending restraint will be pivotal to this.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout