Newington College decision to enrol girls throws spotlight on boys’ education

The blow-up this week over the controversial decision by an elite Sydney boys school, Newington College, to enrol girls has thrown a spotlight on boys’ education. Has the gender equality push gone too far?

In classrooms and prison cells, Andrew Humphreys has watched boys fall through the cracks of Australia’s education system. As a teacher and social worker, he saw learning difficulties manifest differently in boys and girls.

“Girls with poor literacy tended to be quiet, whereas boys would be naughty,” he says. “This started the pathway to punishment, anger, school suspension and crime. Ninety per cent of our prison intake is male and about 90 per cent of those men are illiterate when they enter the justice system.”

Humphreys, who is semi-retired but volunteers at a Victorian youth court, case-managed 27 teenage boys convicted of crimes in the early 1990s.

“Only one of them could read and write, and he hadn’t been educated in Australia,” Humphreys recalls. “He’d been educated in an upturned water tank in a refugee camp.”

After decades of affirmative action to help girls catch up educationally, now boys are falling behind. They are likelier to struggle to read and write, and have lost much of their academic advantage in maths and science.

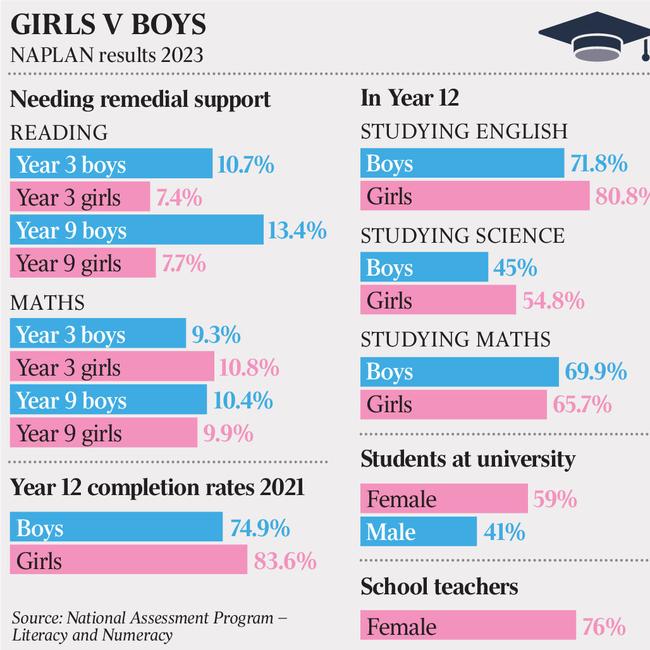

More girls than boys are studying science subjects in year 12 and 59 per cent of university students are female. Boys are kicked out of school at three times the rate of girls, and are likelier to drop out of high school.

‘There’s a tendency for boys to want to perform in front of girls, to strut their stuff, and there are notes going around in recess and lunch to hook up.’

Has the gender-equality push gone too far? In a schooling system that rewards sitting still and colouring between the lines, with a curriculum biased towards long and complex written assessments, are boys being punished for being boisterous, inquisitive and fidgety?

The National Disability Insurance Scheme has been flooded with children diagnosed with autism, 70 per cent of them boys. Astoundingly, one in every eight boys aged five to seven and one in 20 girls the same age are part of the NDIS, mainly for autism or developmental delay. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is not funded through the NDIS but the symptoms of boredom and hyperactivity may manifest more obviously in boys than girls.

Centre for Independent Studies education program director Glenn Fahey warns that “behaviour in schools is overly therapised”. Teachers have been known to ask parents to obtain a medical diagnosis of learning difficulties to attract extra support in the classroom.

“It could be that because so many educators struggle to manage classrooms, that is leading them to seek out additional support, and that might lead to over-diagnosis of behavioural problems,” Fahey says. “They seek out conditions and diagnoses that could just be regular behaviour and conduct. Boys do identify and present more often in relation to attention-related disorders.”

Fahey says teenage boys trail two years behind girls, on average, in writing skills, based on NAPLAN test results. In mathematics – a traditional strength for boys – girls largely have caught up and are just two months behind boys.

The 2023 NAPLAN results show that 10.7 per cent of boys in year 3 require remedial support for reading, compared with 7.4 per cent of girls. By year 9, 13.4 per cent of boys are the functionally illiterate – nearly double the rate of girls. In mathematics, roughly one in 10 boys and girls needs remedial assistance right through primary and high school.

Boys are falling further behind girls in reading and writing the longer they are at school. This concerns Fahey, who warns that boys who excel in crunching numbers may struggle to articulate mathematical problem-solving in written assignments.

“A major development in assessment methods has been the use of word-based problem-solving, which was intended to be a way of levelling girls’ achievement in maths,” he says. “There was a fear that timed assessments would create anxiety. But we can conflate students’ difficulty with language, with struggling with a maths problem. They’re not testing the underlying arithmetic skills. We don’t value arithmetic fluency enough in maths skills, and mastering key foundational maths facts quickly and accurately is key to success later in more complex maths.”

Grattan Institute school education program director Jordana Hunter – one of the group of experts advising education ministers on priorities for the next school reform agreement – is calling for more focus on boys’ literacy.

“We need to get boys back on track,” she says. “The trend of boys falling behind girls is worrying. We need to make sure that by the middle of primary school boys are confident readers. If boys are lagging in reading we will see the effects of that in worded questions in mathematics and other subjects.”

Problems with learning can manifest as “bad behaviour” in classrooms. “This may cause more acting up,” Hunter says. “It’s a way to divert attention from the fact they can’t do the work, because they don’t want to look dumb in front of their peers.”

Boys are almost three times likelier to be suspended or expelled from school, based on disturbing data from state education departments. In NSW, 22,723 boys were given short suspensions in 2020, compared with just 7911 girls, for “continued disobedience” or aggressive behaviour.

Another 8949 boys and 3270 girls were given long suspensions of up to 20 school days for physical violence, criminal behaviour and possessing weapons or drugs.

Not only are boys likelier to be kicked out of school but they also are most likely to drop out before finishing year 12. While 84 per cent of girls finished year 12 in 2021, the completion rate for boys was only 74.9 per cent.

Fewer boys go on to higher education. Among 25 to 34-year-olds, 52 per cent of women have a university degree, compared with just 38 per cent of men. Young men also are likelier to be unemployed – 8.3 per cent of 15 to 24-year-old men are not working or studying, compared with 7.2 per cent of women.

In their formative years, many boys may not come across male role models at school, given the feminisation of education as a profession. In primary schools, 82 per cent of teachers are women, while the proportion in high schools is 61 per cent.

The blow-up this week over the controversial decision by an elite Sydney boys school, Newington College, to enrol girls has thrown a spotlight on boys’ education. The storm of protest shows that many parents prize single-sex schooling for its focus on the learning strengths and differences of boys and girls.

“It’s the camaraderie and lack of distraction,” says Newington parent Dimitri Burshtein, whose son is finishing his Higher School Certificate at the 160-year-old Uniting Church GPS school, where parents pay $38,884 a year in tuition fees. “Boys are performative in front of girls. A boys school has a different culture. There’s a brotherhood, and it allows them to be more open and transparent.”

Newington College took old boys by surprise when it announced its decision on Monday to transition to a co-educational school within a decade. “Our students will enter a world that will require them to walk and work alongside all genders collaboratively, respectfully and empathetically as colleagues, employers, employees, partners, parents and friends,” Newington College council chairman Tony McDonald told the school community.

“We believe the best way to prepare them for these roles is for different genders to learn alongside each other in an everyday, unremarkable way during their childhood and adolescence.”

In a remarkable backlash, nearly 1200 people have signed a Change.org petition for the school to remain a “a place for boys to grow into men, surrounded by their brothers”.

One parent complained that “pandering to the woke madness of the 2020s is a terrible look for this venerable school. There are innumerable benefits for boys to learn and grow without the distractions of girls during adolescence.”

At The King’s School – a prestigious Sydney boys school that counts former NSW premier Mike Baird and film director Bruce Beresford among its alumni – boys have a safe space.

Headmaster Tony George says boys can struggle in co-ed classrooms “set up for everyone to sit down, prim and proper, with chat groups and conversation”.

“Boys have a Y chromosome, which means boys have an onboard steroidal pump that kicks in with the onset of adolescence,” he says. “Boys just tend to be more boisterous and active.”

George says the curriculum has become more feminised: “There’s a lot of emphasis on having a conversation group, talking about how you feel. Boys do tend to be less verbal. But boys need to be vulnerable and be able to share their feelings.”

At The King’s School, the single-sex space means boys “are able to talk more openly with their mates about how they feel and their experiences”, George says. At co-ed schools, “there’s a tendency for boys to want to perform in front of girls, to strut their stuff, and there are notes going around in recess and lunch to hook up. That doesn’t happen at a boys school.”

Newington College has joined the growing trend of single-sex schools merging or boys schools admitting girls – most often for financial stability to prop up enrolments. Barker College and Marist College in Sydney and Canberra Grammar already have transitioned from boys schools to a co-ed model, with the prestigious Cranbrook school in Sydney to follow in 2029. In Brisbane, the girls-only Clayfield College is one of the rare girls schools to accept boys.

Only 7 per cent of students in Australia attend the nation’s 304 single-sex schools – 177 for girls and 127 for boys. Nearly half the single-sex schools are in NSW, with a quarter in Victoria and 19 per cent in Queensland.

A recent study by the Kathleen Burrow Research Institute, commissioned by Catholic Schools NSW, found that students perform better academically in single-sex schools, after analysing NAPLAN results for children in years 3, 5, 7 and 9. It reported “a modest academic advantage for single-sex schools, with the advantage generally greater for boys schools than girls schools”.

“A particularly high lead is seen for boys schools in numeracy, but little effect is seen for girls schools in reading,” the study concludes.

At The King’s School, headmaster George says boys are “feeling blamed and accused” at a time when the #MeToo movement has put the focus on “toxic masculinity”. “Boys can’t be physical and adventurous and outdoorsy and do manly stuff because it’s politically incorrect,” he says. “At the moment, anything that’s physical gets labelled as toxic. Don’t blame boys for being boys.”

From “wiggle chairs” in the library – designed for fidgety boys – to organised sport, The King’s School encourages students to “get up and move around”. “You’ll find that in most boys schools, sport is compulsory,” George says. “A busy boy is a good boy.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout