Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn polarise voters in British election

With party leaders and Brexit polarising Britain, the poll result still hangs in the balance.

The intensifying row over anti-Semitism in the British Labour Party should leave the Conservatives feeling invincible ahead of the December 12 general election.

But Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s repeated refusal to apologise to Jews on Wednesday (AEDT) after Britain’s most senior rabbi suggested anti-Semitism was a “new poison” within the main opposition party, and that it had been “sanctioned from the very top”, is unlikely to shift many votes.

Labour has been dogged by allegations of widespread anti-Semitism among members since Corbyn, 70 — a lifelong supporter of Palestinian causes — took over as leader in 2015.

The Jewish community — and followers of other faiths who expressed outrage at Corbyn this week — made up their mind about his views long ago.

Yet the Tories do not feel secure about their thumping lead in opinion polls.

As The Australian has travelled from Wales to Scotland, to Manchester and across London, there appears to be both a desperate desire to ignore the election noise and the highest level of political engagement in 10 years.

As we enter the final fortnight of the campaign, headline predictions of the Tories winning a majority of more than 40 seats, even 60, and of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s 19-point lead over Corbyn, may be demoralising for progressive Momentum activists, but are they accurate?

Labour traditionally closes ground in the final days. And in the Welsh and Middle England seats the Conservatives must win to form a majority government, the crucial questions are whether Johnson’s Brexit pitch is enough to earn their vote, or if Corbyn has turned them off enough not to vote at all.

Key regions

Voters in small cities in the Midlands and north Wales hold the key to whether the next government will be a Tory majority or a coalition of Labour and the Scottish National Party.

This is not yet nailed on, one Tory insider tells The Australian. This is not yet even the Tories’ election to lose.

After years of Brexit twists and turns, voters’ views on leaving the EU are firm and the parties’ stances were confirmed long ago: Leave (Conservatives and Brexit Party), Remain by various means of a second referendum (Labour), or immediate revocation (Liberal Democrats).

The Tories’ challenge is keeping the electorate focused on Brexit when the populace wants to hear anything but. “The British public is utterly sick of Brexit and would cheerfully pay someone 10 quid to talk about something else,’’ says Patrick Dunleavy, political analyst with the London School of Economics. “Tories relying on Brexit strategy may not survive.’’

Whenever Johnson spruiks the message “Let’s get Brexit Done’’, people loudly groan.

Labour’s positions, as fiscally and ideologically extreme as they are, have increasingly begun cutting through.

It is the undecided and swing voters who Johnson has to win over to fend off a Labour rise.

The Tories benefited enormously from the severe slump in Brexit Party support after leader Nigel Farage decided not to contest 317 Tory seats.

But Labour also has gained as Liberal Democrat supporters increasingly indicate they will vote tactically to keep the Tories out.

Political analyst John Curtice from Strathclyde University warns: “The Conservatives’ seemingly comfortable poll lead would soon be reduced if the Remain vote were to coalesce behind Labour, rather than be split between Mr Corbyn’s party and the Liberal Democrats, who still have just under 30 per cent of the Remain vote.”

Anti-Brexit businesswoman Gina Miller urges Remainers to vote tactically so as not to split the Remain vote in tight seats. “People are getting despondent when they read the headlines, forgetting that in 2017 the 15 per cent lead was supposed to translate to a 100-plus-seat majority for Mrs May,’’ she says. “Remain United’s data points to a Boris Johnson majority of 70 seats, but this could shrink to zero with pro-Remain smart tactical voting, as it did in 2017.”

Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson has positioned her party as opportunists, wanting to revoke Brexit on day one. But the party is still haunted by five years as a coalition partner with David Cameron’s Tory government — when they sold out students and backed rises in tuition fees.

Unpopular leaders

Corbyn is regarded as anti-Semitic and inept, and is deeply unpopular; Johnson is generally perceived as untrustworthy. Both have negative popularity ratings, but most Britons vote according to party policies, not personal leadership.

“Johnson is quite controversial,” Dunleavy says. “The steps he took before the general election — the prorogation of parliament and the very strident affirmation the UK will leave the EU on October 31 and monkeying around on leaving on a no-deal basis — means he is polarising. People who like him like him a lot, those who don’t like him distrust him a lot.’’

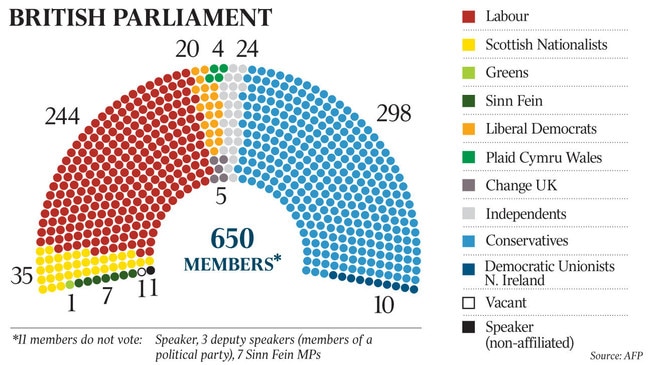

As for the Labour leader, Dunleavy says: “Corbyn has 22 per cent people favourably inclined towards him and 62 per cent who are not. He is quite a drag on the Labour Party performance.’’ To appreciate the Conservatives’ hesitancy is to understand the peculiarities of the British voting system. The most significant aspects, and different to the Australian system, is that it is not compulsory and it is first past the post.

Former Tory prime minister Theresa May attracted a near record 42.7 per cent of the vote in 2017 yet was consigned to a minority government. At the same stage in the election two years ago, the Tories were bounding ahead in opinion polls, only to suffer an embarrassing loss of 13 seats.

While the polling companies were widely castigated for getting that result terribly wrong, as well as miscalculating the 2016 Brexit referendum, there is once again a reliance on a polling method open to wide interpretation.

The polls showing the biggest Tory leads have weighted their sample size to reflect a belief that young people won’t vote in nearly the same numbers as older people. How much they have skewed that mathematical calculation has big implications. So, too, is categorising the polling sample according to how they voted last time, as voter recall is surprisingly fluid (and often inaccurate).

Even though nearly two million young people have swarmed the electoral offices to register to vote in recent weeks — one youth project offered free popcorn to students who signed up in the most marginal seat of Fife, Scotland — there are serious questions. How motivated are voters to turn up on a Thursday to vote?

People younger than 30 are generally twice as likely to support Labour as they are the Conservative Party and, for them, stopping Brexit is a crucial issue, but the environment and austerity are also front of mind.

Experts are divided on whether the timing of the election, unusually close to Christmas, will affect the youth vote because it is also the end of the university term; or the elderly — most of whom vote Tory — because the shorter, colder days restrict the time they can get to the polling station.

If younger voters turn out in crucial electorates — as the lack of proportional representation system means some votes really are more important than others — they could help prop up a Labour-Scottish Nationalist coalition.

Manifestos

Labour came out with its manifesto first, pledging a revolution in politics.

Britain would be radically transformed under Labour — with renationalisation of water, rail, mail, buses, energy and fibre broadband. Corbyn repeatedly boasts that he will bring about “the most ambitious and radical campaign for real change that the country has ever seen”.

Labour has vowed to spend a staggering £400bn ($759bn) to boost schools, provide free infant childcare, free internet, invest in hospitals and the National Health Service, build 100,000 new council houses a year, impose rental caps and scrap university tuition fees. Workers would be given 10 per cent of business shares, a £10 minimum hourly wage and a four-day working week.

The cost would be covered by taxpayers earning more than £80,000 a year and financial hits to businesses big and small.

Shadow chancellor John McDonnell has conceded Labour also would adjust taxes in other areas: inheritance tax, marriage allowance, sugar tax, capital gains tax and a 200 per cent tax increase on second homes.

About a million small-business owners would be slugged on par with big corporations, having their company taxes increased from 19 per cent to 26 per cent. The costings also assume high earners won’t flee the country as their personal taxes rocket to 45 per cent for income earned over £80,000 and 50 per cent over £123,000.

Labour says it will spend £93bn a year on public services, inflicting a tax burden not seen since World War II.

Announcing the Tory manifesto at the same Telford constituency in the Midlands where Corbyn launched his campaign, Johnson promised to spend an extra £2.9bn a year: on 50,000 new nurses and doctors, the scrapping of many hospital parking charges, pothole repairs and the end of the Fixed Term Parliament Act.

But that expenditure comes on top of other initiatives Johnson announced at the start of his prime ministership, including £4.3bn a year on schools, £20.5bn annually on the NHS, and the cost of more police at £1bn for next year.

Even on the most generous of assessments, Labour intends to outspend the Tories by more than three to one, which for the party’s traditional working-class base may be hugely welcomed.

Yet some voters fear the Labour policy is exceedingly neo-Marxist. If there is a Labour rout, it will be because average families fear the Corbyn-McDonnell ideology more than they do Brexit.

This week Johnson was more vague on future expenditure than Labour, such as the costs that will be incurred now that the elderly will not be forced to sell their home to pay for aged care; but he promises that over the term of a Tory government he won’t raise income tax rates, will slightly reduce national insurance payments and freeze value-added tax, the equivalent of Australia’s GST.

That “triple lock’’ may come to haunt Johnson, says Institute of Fiscal Studies director Paul Johnson, as economists believe even a relatively small unzipping of the country’s wallet will have to be paid with higher taxes.

The Tories, he says, offer a “fundamentally damaging narrative: that we can have the public services we want, with more money for health and pensions and schools — without paying for them. We can’t.”

The Tory manifesto suggests health and school spending will continue to rise but “give or take pennies, other public services, and working-age benefits, will see the cuts to their day-to-day budgets of the last decade baked in”, he adds.

But the institute’s Johnson also pans Labour’s plans to substantially increase the role of the state.

“If you want to transform the scale and scope of the state, then you need to be clear that the tax increases required to do that will need to be widely shared, rather than pretending that everything can be paid for by companies and the rich,” he says.

While Tory voters and businesses are concerned about the tax implications and the economic upheaval of a Labour government, the electorate at large is not so fussed.

Only 11 per cent have raised taxation as an issue in the election, on par with concerns for the environment. Brexit is the main concern for two-thirds of voters, but the NHS is an issue for nearly half, especially Labour voters.

Managing the economy is less of a focus than in previous elections, an Ipsos More poll found.

That is why Johnson is campaigning in the marginal seats with promises to fix local problems of securing a doctor’s appointment, allaying fears about the creaking NHS and wanting a pothole-free car ride to work.

Political scientist Tony Travers says the Tories will have to move away from their traditional comfort zones of the southeast and southwest and strike into the Midlands and the North.

The Tories are often disliked in these former industrial areas and they are still associated with the Thatcher government.

“That is where the Tories will try to win, and while some polling shows them doing quite well, they will have to win there in a way that will bring about a big breakthrough,’’ Travers says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout