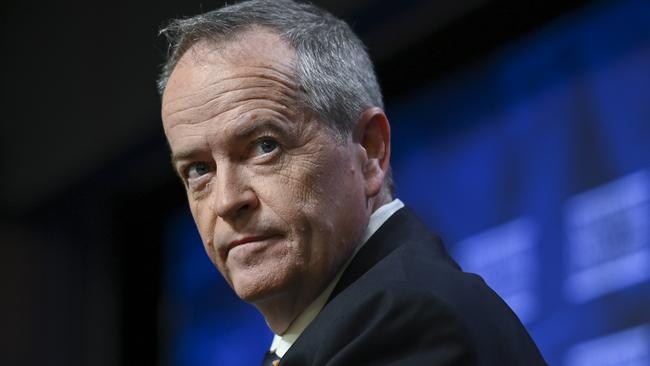

The message in Bill Shorten’s exit that has Labor figures panicked

Bill Shorten’s resignation suggests a deeper fear, even panic, within the party about what has been achieved by the Albanese government — and what the Greens have in store.

But the message from Shorten’s resignation announcement inescapably goes beyond his personal prospects, even beyond whether he thinks Labor will win or face minority government at the next federal election, and gives voice to wider concerns within the party about what has been achieved in the first Labor government in more than a decade and what will be possible if Anthony Albanese loses majority government.

It has been obvious for a while that Shorten – no matter what happened – would not be Labor leader again: that is now reality. Yet the concerns of other senior Labor figures are not as straightforward as they are for Shorten and suggest a deeper fear, even panic, that after so long in opposition the party has not succeeded in implementing a real Labor agenda in government and will be captive to a Greens agenda in minority government.

Of course, the Prime Minister believes Labor will win a majority at the federal election next year as he campaigns against the Greens in inner-city areas and banks on Peter Dutton not being able to reclaim the Liberal seats lost to the teal independents.

It remains the political reality that a Labor victory, even a negotiated minority government, is more likely than a Coalition victory given historical precedent and the simple electoral maths.

But unforced errors, cabinet leaks, irrepressible scandals, backbench revolts, MPs’ dissatisfaction with ministerial actions, blame-shifting failures to ASIO and the Reserve Bank, retreats on pledged targets and election promises suggest ministers are frustrated and making mistakes.

Through no fault of Shorten’s or any intent, his departure ahead of the next election will inevitably add to the sense of uncertainty and how fundamentally the political and electoral architecture in Australia has changed across the past 20 to 30 years of Shorten’s public career.

From 2006 when, as national secretary of the Australian Workers Union, Shorten shot to prominence on the national stage as the face of the Beaconsfield mine disaster until he lost the 2019 election, he had a fortuitous and meteoric rise in politics following his election as the member for Maribyrnong in 2007 as part of the incoming Rudd Labor government.

In the wake of the Tasmanian mine collapse and the miraculous survival and rescue of two AWU members trapped underground, Shorten – co-incidentally the preselected Labor candidate for the Melbourne seat of Maribyrnong after defeating the sitting Labor MP – became a national identity and immediately drew comparisons with former ACTU leader and prime minister Bob Hawke as a centre-right leader.

Shorten was appointed as the new parliamentary secretary for disabilities, which was to set a path for his future ministerial career to implement and later reform the National Disability Insurance Scheme – again the right man at the right time.

Shorten’s factional power as a Victorian right-wing leader made him crucial first to the leadership downfall of Kevin Rudd as Shorten supported Julia Gillard, then to the downfall of Gillard’s leadership as the reality of a Rudd return dawned.

When he emerged as the ALP leader after Rudd’s defeat in 2013 at the hands of two-term opposition leader Tony Abbott, Shorten, like all others, was scarred by the turmoil of the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd years that burnt two capable Labor leaders in the space of two terms.

On Thursday, Albanese paid tribute to Shorten’s achievement in 2013 after Labor’s traumatic loss and division.

“Bill took over in the wake of a demoralising 2013 defeat,” the Prime Minister said. “He united the party, he re-energised the caucus, he saw off two prime ministers and he rebuilt Labor into a strong opposition and a genuine alternative government. Through his years as leader, no one worked harder than Bill.”

Standing in the Prime Minister’s courtyard at Parliament House on Thursday, Shorten said: “When I was voted Labor leader after the 2013 election, the party, as the Prime Minister said, was at a low ebb. We were reduced to 55 seats, our worst result since 1996. We were up against an ascendant Abbott government with a fierce ideological agenda.

“We looked to Australians not just for their approval, we trusted in their instinct for fairness. We argued on the policy, we took the responsibility to put forward positive alternatives, and put pressure back on the other side.

“Not every idea succeeded, I understand that. We didn’t win every battle. But Labor, we never stopped trying.

“Whether it was defending Medicare or real action on climate, marriage equality, advancing First Nations representation in our ranks, championing wages and conditions, setting a target of 50 per cent of women MPs by 2025, the banking royal commission or tax reform. These were hard fights, all worth having.”

While trying to keep Labor together, while trying to stick to old Labor principles and policies and re-establishing contact with the ALP base, Shorten had the fortuitous advantage of the overweening ambition of Malcolm Turnbull, who assisted mightily in the destruction and removal of Abbott as Liberal prime minister.

Turnbull demonstrated a lack of political understanding and leadership, and by the time of the 2016 election Shorten – as opposition leader for just one term after a crushing electoral loss – outperformed the Liberal prime minister, and Labor came within just one seat of victory.

A Nationals victory in one seat ensured Turnbull survived for the moment, but it also meant Shorten was assured of a second term as Labor opposition leader. Right man, right place, right time.

As Albanese said at the Shorten resignation announcement, “Bill” had done away with two Liberal prime ministers – Abbott and Turnbull – and was expected to beat Scott Morrison, the third Liberal leader in three terms, at the 2019 election. Shorten embarked on an ambitious Labor agenda from opposition, seeking changes to taxation on negative gearing and franking credits, tax changes for high and lower income earners.

He offered a referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament with a constitutional convention, and he offered to roll back budget cuts and to defend Medicare.

During the 2019 election campaign Shorten made big spending promises and offered to help those on lower incomes. He was accused of class warfare when he said self-funded retirees using negative gearing and franking credits were drinking champagne on the backs of yachts.

The polling suggested Shorten’s big-spending, centre-right Labor campaign was succeeding against Morrison as the leader of a divided Coalition. Shorten was told he would win and even – in tribute to Hawke – gave up campaigning on the last Friday night and took travelling journalists to the pub.

But suddenly Shorten was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Morrison had the “miracle” victory that had eluded Shorten in 2016. Labor was still in opposition and, unlike Gough Whitlam, Shorten wasn’t going to get another crack at opposition leader.

But, while he didn’t win, Shorten laid the foundation for an almost certain Labor victory in 2022 because Morrison had used up all his luck – the 2019 election reduced a large number of Coalition seats to vulnerable margins, Labor had remained united and the base moved back.

Albanese’s 2022 victory was built on Shorten’s loss and the strategy was to reject Shorten’s big ideas and to run a policy-free agenda. There also has been a quiet adoption of many of the policies and ideas Shorten promoted in 2019.

Shorten was given the prize of fixing the NDIS and delivering $10bn in savings as a central plank to budget repair, which he tried to portray as an aspirational target because he knew it could not be achieved and hasn’t been.

When asked about his ambitious 2019 election agenda, Shorten said: “I’m proud of the fact that we took policies to the people where we were honest and upfront. Some of the ideas … were bold and audacious. But this government’s now been able to succeed because they got elected in implementing some of the threads of the hard work, from climate change to a Future Made in Australia, to training our apprentices.

“In terms of the tax reform propositions (negative gearing/franking credits), the reality is that the verdict of the people was that they weren’t ready for that.

“The verdict came in, I accepted that. But I am proud that we put our propositions forward. Labor’s at its best when they know what we stand for and they will fight for things.”

While Shorten didn’t talk about his “few regrets”, there was a wistful air when he talked about how some of those ambitious ideas were now happening: “Now, I absolutely support and congratulate the Prime Minister. He took us from 2019 and closed the deal with the Australian people. And that just meant that all of the good ideas, which I’d like to have seen, a lot of them are happening.”

There was never any doubting Shorten’s willingness to serve as Labor leader, or his commitment to the ALP and its supporters, but his departure ahead of the next election will raise the issue of whether he thinks Labor can achieve what he would like it to achieve if there is a hung parliament.

The appeal to a centrist Labor base is not Shorten’s only advantage for the Albanese government that will be missed, but also his ability to speak more directly, passionately and honestly about issues that have troubled the government, from immigration to pro-Palestinian anti-Semitism.

Often Shorten has been the right man to say the right thing at the right time when others failed to be forthright and unambiguous.

Bill Shorten was once the right man, in the right place, at the right time – until he wasn’t. The National Disability Insurance Scheme Minister’s announcement this week that he would be resigning from the Albanese Labor government and the parliament in February next year to take up the role of vice-chancellor of the University of Canberra encapsulated that political theme for the former Labor leader.