We are also hearing calls for Privacy Act reforms to better protect citizens whose personal information is retained by businesses. There’s a growing clamour as politicians share their anger and concern over what has happened.

But are these politicians hypocrites? Yes, they absolutely are.

Major political parties operate sophisticated voter-tracking software without the consent of voters and their databases contain enormous amounts of personal information about all of us. Every major-party member of parliament has voter-tracking software operating in their office and they won’t let you see it even if you ask.

Labor’s database is named Campaign Central (previously Electrac), the Coalition’s database is named Feedback. Political parties get automatic electronic access to the electoral roll, with monthly updates also freely provided by the Australian Electoral Commission.

Basic information these party databases have includes our name, date of birth, address and, for many of us, a lot more. Parties seek to harvest as much information about us as they can, with the aim of using such details to better target campaigning to win our votes.

So when you write to your MP, get doorknocked, give details at a street stall or answer questionnaires or party polling, expect the information you provide to make its way into one of these databases. If they represent you in official correspondence to a department, whereby you might include all manner of sensitive personal information, expect those details to be uploaded into the database.

How good are the protections on such personal information, I wonder. The databases have been in operation for decades, and the worst part is that you have no right to access information on yourself or even check if it is accurate.

That’s because the major parties have excluded themselves from Privacy Act rules other private organisations must abide by that require them to disclose any information they retain about their customers when it’s requested. You can’t even use Freedom of Information laws to try to access what information the parties have stored about you because political parties are private organisations, even though taxpayer-funded political staff upload information in the databases. FOI applications can be used only to access public sector information.

In other words, political parties neatly fall between accountability checks. They write the legislation, they control the rules.

What if these inaccessible and potentially inaccurate party databases are hacked? How good are their firewalls? Even if there are adequate cyber protections in place, hundreds upon hundreds of political staff, politicians and party operatives have access to the databases every day anyway, potentially allowing them to violate your privacy by accessing data on you. Or they could leak it. They could even amend your information, often without safeguards to discourage doing so inappropriately.

There are inadequate safeguards in the system to ensure misuse can’t happen. Given what we know about the culture inside parliament and among the political class more generally – just read the Jenkins review – you can only imagine what awful things might get tagged against some people in these databases. And you can’t even get access to check what’s on file about you.

So yes, major-party politicians bleating about Optus are hypocrites who are turning a blind eye to one of our nation’s most outrageous privacy violations, in which they partake and which is ongoing. In fact the sophistication of these databases continues to develop, making them only more invasive as they remain unaccountable. And that is to say nothing about the damage that could be done if that data were to be hacked.

Here’s another fun fact: while I understand both major-party databases locate their mainframe servers domestically, that wasn’t always the case. Not long ago the private information they harvested and accumulated without our consent was housed overseas because doing so was cheaper. That is extraordinary on so many levels.

While our politicians might think it’s no big deal to build profiles of voters without their consent and without accountability and accuracy safeguards, the fact such databases are routinely consulted before appointments are made to government boards, for example, highlights another part of the problem: an effective hollowing out of the principle of the secret ballot.

These databases are used as part of the vetting process to ensure appointments governments make don’t include people whose information suggests they vote the other way or have been critical of the government at potentially any point in time since data started to be accumulated. You might find yourself black-listed.

The situation would be all the more serious if any party drifted from Australia’s commitment to a broadbased democratic culture. The recent Italian election might give anyone complacent about such voter-tracking software pause for thought. What if, one day, extremists take over our major parties, with all the information these databases contain?

If our politicians are serious about holding Optus to account, including wanting to take a fresh look at the Privacy Act, they also need to self-reflect. Consider removing the Privacy Act exemption that political parties enjoy. Submit their databases to rigorous testing to ensure they are safe from hackers. Allow voters to access what information is stored about them and to correct the record when it is inaccurate or when observations included against people’s names are offensive or defamatory.

I first wrote academically about voter-tracking software years ago. My first long-form refereed journal article in the Australian Journal of Political Science meticulously detailed the operating system of Feedback, as it was back then, 20 years ago, highlighting reasons to be concerned. It got a few headlines, then the political news cycle moved on.

From what I’m led to believe the degree of sophistication now built into both major parties’ software leaves the concerns expressed back then in the wake of the reasons to be worried about privacy violations now.

If the Optus scandal has the unintended consequence of stoking public concerns about party databases and what they store on all of us, leading to this article being followed up with detailed investigative journalism and scholarship, that at least will be a positive to come out of what has been a profoundly bad situation for so many current and former Optus customers this past week.

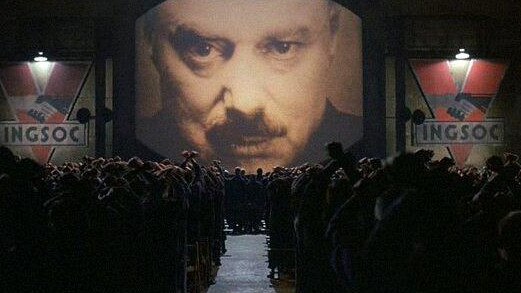

Because when it comes to our major parties, Big Brother trumps democracy.

Peter van Onselen is a professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

Both major parties are pouring scorn on Optus for its customer-data breach, rightly so. If reports are accurate that the company’s defences weren’t up to scratch, that’s simply not good enough.