Big business will be hunting for bargains in the pandemic wreckage

In this mutant recovery there’s a danger that healthy competition could be throttled as big business hunts for bargains among the wreckage.

This week’s national accounts showed a 3.3 per cent jump in gross domestic product in the three months to September. Company profits rose by 3.9 per cent to be 18.2 per cent higher across the year. The S&P/ASX 200 is 46 per cent above its low in March and only 7 per cent below its pre-pandemic high.

The profit surge is due to a rebound in consumer spending, especially on services such as dining and elective surgery, as restrictions on trade and travel were eased everywhere except Victoria. The Morrison government pumped almost $100bn into supporting businesses in the June and September quarters.

Canberra’s two biggest subsidy programs in modern times, JobKeeper ($71bn) and boosting cashflow to business ($28bn) across six months, tell the story of the virus, the cure and the long crawl back.

The five big banks — the ones Morrison as treasurer hit with a levy and roasted with a “Nobody likes you, anyway” — were cut out of JobKeeper. Plus companies with a turnover above $1bn had to show a 50 per cent drop in sales to qualify for the wage subsidy scheme, while those below the threshold were required to show only a 30 per cent drop.

Naturally, the government is close to big business, depends on it in all sorts of ways, but often strikes populist poses in public. In the case of emergency support, the thinking was that large companies had easy access to credit and the wherewithal to absorb the pandemic’s supply shocks. Ditto the universities.

Still, some big companies did get JobKeeper. According to figures provided to the Senate’s COVID-19 committee by the Australian Taxation Office, 223 entities had received more than $10m in the first six months of the wage-subsidy scheme. Across that period, the JobKeeper rate was $1500 a fortnight. On average, those big businesses were supporting 1537 employees.

As some semblance of normal commerce returns, we can see the relative strengths of big and small employers. According to the latest payroll data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, companies with more than 200 employees are back to their pre-pandemic headcounts.

Sure, not every worker has returned to full hours, as companies re-engineer their operations, but that is changing. For small businesses, employing fewer than 20 people, payrolls are 6 per cent below their levels of mid-March, when the nation hit 100 coronavirus cases. Medium-sized company payrolls are still 5 per cent down.

Australia is being reshaped by the pandemic. It will take years to tell whether the damage is persistent or permanent. There will be scarring for inexperienced workers and new graduates, and a lower capital stock because of the investment strike.

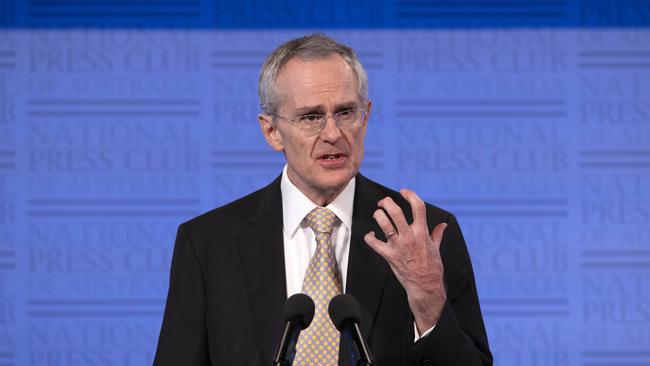

Australian Competition & Consumer Commission chairman Rod Sims says dominant companies could entrench their supremacy as COVID-19 causes business failures and accelerates moves to online commerce and data collection.

“Major disruption often allows the strong to get stronger, to the detriment of our economy and society,” Sims told me. “The structure of the economy can be quite fragile. Then you have a pandemic and all sorts of things are disrupted that change industries. We don’t want firms failing and then being sold to their closest competitor or to the dominant player in a market, whether that’s in finance, the energy sector or aviation.”

Sims is pushing for a tougher merger law next year and better regulation of the prices and services of monopoly infrastructure providers. These and other competition reforms would improve our economic dynamism.

Referring to growth theory, where higher living standards are a function of population, productivity and the savings rate, economist Sims says an excess of market power damages innovation and productivity.

“When you have a monopoly, you charge more and give less,” he says. “You are less likely to innovate your way to success, more likely to become fat and lazy, use acquisitions to gain more market power at home.”

Canberra’s key advisers and regulators fear a lessening of competition from company failures could hurt those drivers of growth. Forthcoming Treasury research shows declining competition could account for at least one-fifth of our sagging labour productivity performance.

Preliminary Treasury analysis of payroll data shows employment within industries has tended to become more concentrated among the largest firms.

In its October financial stability review, the Reserve Bank noted business failures would increase in coming months, with survey evidence suggesting one-quarter of small businesses would fail if income support was withdrawn: “At least 10-15 per cent of small businesses in the hardest-hit industries still do not have enough cash on hand to meet their monthly expenses.”

As the robust GDP result hit screens on Wednesday, RBA governor Philip Lowe was asked at a parliamentary hearing about the bank’s forecasts for jobs and output, which now appear at the pessimistic end. The central bank believes we won’t hit our pre-crisis GDP level until the end of next year with 6 per cent unemployment. Private economists expect we’ll recover the GDP mark by June.

Was the RBA’s view due to the government cutting spending by 17 per cent next financial year? Lowe says the main issue is that there are long-term consequences from the pandemic.

“It is doing damage to many businesses,” he says. “Businesses are failing or they are going to fail. I think the insolvency rate at the moment is low but it is going to rise. Businesses are going to need to restructure. Business models are changing. I think there are permanent effects on labour demand.”

The competition tsar vows to be vigilant in preventing big fish eating minnows. Sims cites the Google and Facebook playbooks, and how their immense market power has destroyed the business model for news. “At this stage we have not seen smaller, struggling operators being acquired by larger competitors during the pandemic,” Sims says. “But there is a significant risk that this could happen, particularly as various support schemes are unwound, so we are watching this situation closely.”

There are exceptions to the winners and losers story. Qantas is the most prominent, yet not the only, casualty of border closures and the slump in travel. It faces the full force of structural change from new ways of work and trade, as well as the ongoing squeeze and barrage of woe in this distorted new order.

Big companies have had a “good” pandemic and in this mutant recovery they will regain profitability faster than small players. Soon, if not already, the strong will be on the prowl to pick off the weak as our economic machine is remade. That’s the creative annihilation of capitalism that governments seek to manage for the greater good.