Cory Bernardi bows out, integrity intact

He may be unique in the annals of Australian political betrayal, but self-interest never motivated the Liberal conservative senator.

In the final months of 2016, a jaded Cory Bernardi was cooling his heels on a 12-week parliamentary secondment to the UN in New York.

The conservative Liberal senator was fed up with the leftward drift of the party under the prime ministership of Malcolm Turnbull, who had limped across the line at an election earlier that year having wrested the leadership from Bernardi’s good friend Tony Abbott the year before.

READ MORE: Cory Bernardi bows out of federal politics, no regrets | Bernardi retirement boosts govt in Senate

Bernardi, a lifelong Liberal supporter, was having dark thoughts. Through circumstance, he was now living in the same city as his mentor, former Howard government minister Nick Minchin, who was then the Australian consul-general in New York.

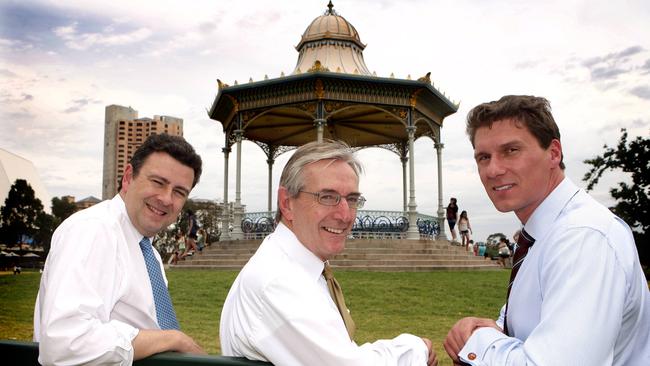

Minchin had sponsored Bernardi’s rise through South Australian Liberal ranks in the early 2000s as a powerful and intelligent young conservative, challenging the state’s historic moderate domination. Minchin knew where Bernardi’s mind was at, and he set to work.

“While Cory was in New York we spent many a while together talking it through,” Minchin tells The Weekend Australian.

“There were quite a few of us who had difficulties with Malcolm’s view of the world. But I did a lot of work to persuade him not to leave. I wanted him to grit his teeth and hang in there. I understood what he was thinking because I had also been shattered by the Turnbull coup against Abbott, but I was desperate to keep him in the party.”

Minchin’s pleas failed to convince Bernardi, who on his return home in 2017 quit the party in disillusionment at Turnbull’s leadership and founded the unsuccessful Australian Conservatives.

“I understood why he did it. But he sacrificed what would have been a long and successful senior ministerial career. He could have gone all the way,” Minchin says.

This week, Bernardi announced he was leaving politics for good, but with no sense of regret at having quit the Liberals or derailing his own career.

“I remember those chats with Nick and he definitely did sound a cautioning note in our conversations,” Bernardi tells The Weekend Australian.

“I had confided in a couple of people about where I was at. He said that I needed to realise what it would mean for my life and my career. It was a mentor’s concern, that I needed to understand the implications of leaving. But like all my good friends he understood the motivations for my decision. And I can console myself in the fact that the people who said bad things about me after I quit were already saying bad things about me before then anyway.”

Bernardi may be unique in the annals of Australian political betrayal in that he is the only politician to have “ratted” on his party and still received a warm send-off from many of the people he abandoned.

Bernardi, who turned 50 this month, will leave the parliament at the end of the year, with the SA Liberals to hold a fresh preselection to find his replacement.

The announcement came almost three years after he walked away from the Liberal Party, for whom he was elected a senator for South Australia back in 2006.

Unlike most other famous political defections and departures, Bernardi’s was motivated by neither spite nor self-interest.

He wasn’t Mal Colston walking out on Labor in 1996, enraged at having been denied the glorious honour of elevation to the Senate deputy presidency.

Bernardi’s reasons — like Bernardi himself — were 100 per cent ideological.

He had come to regard his relationship to the Liberal Party, then under the leadership of Turnbull, as akin to a bad marriage, where he felt that his own role was pointless and that he was living a lie remaining in a party that, he believed, was swinging leftward away from its traditional values.

And rather than acting out of self-interest, he acted against his own interests, in that the party he founded on his departure, Australian Conservatives, endured what Bernardi described with trademark bluntness as “an unmitigated disaster” at this year’s election, polling just 16,000 first-preference votes in his home state, less than one-third the result enjoyed in South Australia by One Nation.

The fledgling party had been caught in a pincer movement with traditional Liberal conservatives returning to the fold once Scott Morrison replaced Turnbull, and the headline-grabbing Pauline Hanson scooping up disaffected blue-collar and regional right-wing voters.

“The inescapable conclusion from our lack of political success, our financial position and the re-election of a Morrison-led government is that the rationale for the creation of the Australian Conservatives is no longer valid,” Bernardi wrote on the party’s website in June on announcing its deregistration.

Bernardi is now in the business of cleaning out his office in the inner-eastern suburb of Kent Town ahead of a return to the family business where he received his start in the 1990s, as publican of the now-defunct hotel Bernardi’s, a rollicking city pub propped up by an army of drunken journalists from the neighbouring Advertiser building.

Bernardi became famous for a string of so-called controversies that stemmed from his enthusiasm for plain speech, be it on issues such as banning the burka or his defence of the traditional family unit. While in New York, he had a front-row seat for the unheralded rise of Donald Trump, deliberately goading his lefty critics back home by posing on social media wearing a red “Make America Great Again” baseball cap. He says this week he has been reflecting on the battles he has had during the past 13 years, most of which emanated from his lived commitment to freedom of speech. He fears that censorship, self-censorship and a growing inability to agree to disagree are now the biggest threat to the exchange of ideas.

“A lot of the battles I had were really because people weren’t ready for the conversations,” he tells The Weekend Australian.

“In the fullness of time we can now have mainstream talk about the problems with China and its interference in our political system, the merits or otherwise of high immigration levels, or altering our cultural norms. I am happy to have participated and in some cases led those debates.

“If we stifle free speech or the battle of ideas we will go backwards as a country. I know it’s not what Australians want.

“When I consider the relationships I have formed in Canberra, there are people I respect on all sides of the political divide. It’s because I respect their intellect, their consistency, their application of principle, and the fact that they are prepared to counter the political battle in a rational and sensible way. The ones I have the least respect for are those who are reactive, emotionally driven, rather than driven by an actual factual nature.

“We can’t have a society where we say ‘we are going to denigrate your character because we disagree with what you say’.

“Now too often it’s about shrillness and denigrating others. Any society where 100 per cent of the people are agreeing 100 per cent of the time is a false one. You can go to North Korea for that.”

Minchin says that when Bernardi emerged on the SA political scene in the late 1990s, he was keen to enlist him to the cause in a state where the party had been historically dominated by small-l Liberals. At the time, Minchin was at the height of his enmity with moderate powerbroker Christopher Pyne. The Howard cabinet also replicated the SA factional split, with Minchin and foreign minister Alexander Downer flying the flag for the Right in a sometimes uneasy coalition with moderate ministers Amanda Vanstone and Robert Hill.

“When I got to know Cory I was struck by our common judgment on a whole range of issues,” Minchin says. “He and I shared a common view of the world. He was a fellow traveller for me, a fellow conservative. He was also a very commanding figure, and a good mate. A loyal mate. Someone who was keen to get stuck in and help the party.

“My friends and I were always on the lookout for young conservative talent to bring through the ranks. He wasn’t someone who was there out of ego or a thirst for self-promotion. At the time the moderates did have a bit of a grip on the younger side of the party and Cory helped challenge that. He did it by being honest and direct. He was never a game-player, he was never devious, he was what you see is what you get, not like some of the cockroaches that scurry around.”

Bernardi feels no qualms about ending his career the way he did.

“I don’t take any angst or unhappiness out of this. I’ve had a wonderful journey and I’ve met some extraordinary people. Your opponents often make you better. The qualities I admire in others — integrity, honesty, resilience — are all enhanced by your opponents picking on you when they think you’re wrong.”

And while he won’t name names, he confirms that there are several farewells planned in Canberra by his former party colleagues.

“There are a lot of dinners,” he says. “They’re all secret though.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout