Berejiklian, Andrews and hard questions of political integrity

Daniel Andrews now presides over a cover-up whose full dimensions are yet to be revealed.

Berejiklian is in more immediate trouble. She is trapped in the often fatal NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption spotlight, but it is Andrews who is far more culpable, having mismanaged Victoria’s response to COVID-19, and now presides over a cover-up whose full dimensions are yet to be revealed.

The case against Andrews has no optical link to a corruption show trial yet it is more substantial. There are two counts against the Victorian Premier. Andrews has failed in the challenge of the age, fighting coronavirus, a policy dysfunction at state level unmatched since World War II in the human and economic damage it has done to the Victorian public.

Beyond this, Andrews is the centrepiece of one of the most sustained institutional accountability failures in governance in Australia for decades. On display is an entire government — premier, ministers and public servants — denying knowledge of the critical hotel quarantine decision that triggered the second infection wave, an entire government professing ignorance in denial of its responsibility.

This points to a systemic failure of integrity, what seems to constitute a corruption of the polity, where individuals are intimidated, checks and balances don’t function, the public service is politically aligned and institutions are compromised, raising the most critical questions for the state Labor Party.

The Victorian malaise seems to extend into the civic culture. Victoria is the anchor of progressive ideology as championed by the Andrews government yet the crisis has exposed the authoritarian strand in progressivism seen in the repressive laws Andrews wanted and the hatred fomented by his social media supporters against Andrews’ media critics.

In summary, Andrews’ culpability and the damage he is doing dwarfs that of Berejiklian. Andrews presides over a crisis of the system; Berejiklian has been exposed for her personal failures that hurt nobody.

But relative differences, even so monumental, cannot excuse the NSW Premier. Political history is replete with heroes and saints undone by fatal flaws. The NSW Premier relies on two propositions to save herself. First, she stands on her superior governance performance in meeting the health and economic threats from COVID-19. And second, by repudiating any wrongdoing she seeks to mobilise public opinion to defy the adverse judgments made against her this week and the future critical findings by ICAC.

Berejiklian has not been exposed for corrupt behaviour. There is no suggestion of breaking the law or criminal misbehaviour. That would be an open-and-shut case against her. But she is seriously compromised by the phone taps with her former personal associate and MP, Daryl Maguire, revealing the Premier was aware of his lobbying, commissions and business dealings as an MP, but Berejiklian took no action and kept seeing him after he was forced to quit parliament. The case against her is more serious than the inconsequential incidents that destroyed the careers of two previous Liberal premiers, Nick Greiner and Barry O’Farrell, neither of whom was corrupt but both of whom were forced to resign, the O’Farrell case being marginal in the extreme and Greiner’s removal based on unjustified propositions.

There are three realities impinging on Berejiklian that are unpalatable but need to be raised. First, she allowed her personal life to compromise her professional responsibilities. That Berejiklian is a competent, workaholic, goody-two-shoes, single woman entitled to a romantic life and exploited by her disgraced companion cannot exempt her misjudgment.

Second, this is not guilt by association but guilt because she took no action — to terminate contact, report Maguire or report her potential conflict of interest to the government given that contact continued after August 2018 when Maguire had to resign in disgrace from parliament and the Liberal Party. Such inaction assisted her election victory in March last year. While Berejiklian did nothing to assist Maguire, she was compromised as premier.

Third, personal relationships are not necessarily separate from political life, as Berejiklian keeps insisting. For better or worse, the private to a large extent has become the public. The example of former deputy prime minister Barnaby Joyce proves this point, given he had to resign essentially over his personal life. Security agencies know when a head of government keeps a personal relationship secret that invariably raises issues of ministerial conduct.

But Berejiklian is drawing a line in the sand — telling colleagues to back her against the chorus of resignation demands from Labor, some crossbenchers and the anti-corruption lobby.

She seems to have convinced herself she is an innocent party who “stuffed up” her personal life but will not resign “because I haven’t done anything wrong”. It was a potentially powerful defence — a woman, a victim in her personal life, now ready to prove her toughness in political life.

In a sense her stance means the revamped ICAC is also on trial — for its procedures, public hearings and likely future judgments. This week’s public shaming of a female premier because of ethical compromises arising from her personal life was unprecedented in our history and, given private hearings had already been held, raises the question about the nature of such “show trials”.

This impinges on national politics because Australia is going to have a federal ICAC. Both the Morrison government and federal ALP are pledged to such action. But there is intense conflict about the nature, scope and powers of such a body. The public debate about a federal ICAC has been driven by the progressive side of politics and is conspicuous for the wide interpretation of corruption.

Attorney-General Christian Porter spent much of his National Press Club address in November last year trying to inject a badly needed sense of balance and justice into this debate. He warned that a liberal democracy must balance the powers of such a body against the unjustified reputational destruction in which it has engaged, offering as examples former prosecutor Margaret Cunneen, former NSW emergency services commissioner Murray Kear, former police minister Michael Gallacher and Greiner himself from a long list of victims due to ICAC’s abuses of power.

There is a surge of public support for Berejiklian. She has earned that support. Ministerial results do count. The year 2020 has turned Berejiklian into the nation’s outstanding premier whose management of the COVID-19 crisis has been pivotal in saving her state and Australia.

Scott Morrison has praised her, almost daily, as the model against the backdrop of narrow-minded, protectionist, self-interested premiers Andrews, Annastacia Palaszczuk in Queensland and Mark McGowan in Western Australia. Can you imagine what a disastrous mess Australia would face today if NSW had gone the way of Victoria? Morrison needed Berejiklian — and the nation has needed her performance holding NSW together.

Judged by competence, Berejiklian should be elevated. But the issue is integrity and the Berejiklian-Maguire fiasco highlights the complexities arising from corruption bodies. The exposure of Maguire’s misdeeds is highly desirable, but would the forced resignation of Berejiklian enhance or weaken the quality and trust in NSW governance? Would the public interest be served by Berejiklian’s removal?

Alternatively, would her retention signify a decline in integrity? Did ICAC schedule public hearings having decided it would pursue Berejiklian and aware the public impact might bring her down before any formal findings?

Having ICAC operate as arbiter of political morals is now a deeply flawed model. The originating architect of ICAC, former Greiner adviser Gary Sturgess, told Inquirer these debates needed to draw a sharper distinction between corrupt behaviour and loss of integrity in government.

“Corruption has an element of moral turpitude associated with it,” Sturgess said. “Under the NSW ICAC legislation for behaviour to be corrupt it must be illegal or something for which you can be removed from public office. But there are many integrity issues associated with politics and government that do not go that far.

“We need to call out the integrity issues, but without having the powerful and damning association of corruption. I think these are two separate things. I think it is very unfair on people who have not met a standard of integrity, whether it is an old or new standard, to be labelled as crooks or corrupt.”

Sturgess said the nation needed a better discussion between the competing schools — those demanding a federal body duplicate the NSW ICAC and those who want a deeper appreciation of integrity issues that need to be addressed separate from the notion of corruption.

This is a defining comment but lost in the debate during the past several years. The case against Berejiklian concerns her integrity, not her corruption. But the entire ICAC context is corruption and this feeds into the politics. Ultimately, the judgment on the Premier will be made by the NSW Liberal parliamentary party and will be a brew of ethical, self-interested and political calculations. On this criteria her survival is possible but not likely.

Nobody has accused Andrews of corruption. His government, however, is mired in a profound crisis of integrity. It took a hotel quarantine decision that it admits ignited Victoria’s second wave by giving a private firm the contract it was incompetent to discharge.

This led to the deaths of hundreds of Victorians and triggered a deeply flawed sustained lockdown and curfew involving unprecedented strains on individuals, families and business across a state of five million people, drove a mental health crisis, undermined the national economic recovery, triggered new border closures and divided Australia into two domains in the COVID-19 crisis — Victoria and the rest.

Yet the policy foundation for such extraordinary actions was flawed. For example, the punitive curfew was not based on health advice. The severity of the lockdown was driven in part because of the weakness in Victoria’s testing and tracing capacity.

This led directly to the third serious mistake from Andrews, an exit strategy based on excessive case reduction criteria — rejected overwhelmingly by outside health experts — that saw the entire business community lose any remaining confidence in the Andrews government. The Morrison government, frustrated at Andrews’ deceptions, has been reduced to constant appeals to Andrews to ease his harsh restrictions in line with national cabinet guidelines and the practice of NSW.

The Andrews fiasco will take years to finally resolve. The Liberal opposition, if it wins the next election, pledges a comprehensive royal commission. Litigation has been launched on multiple fronts.

The High Court is hearing a case with prominent silk Bret Walker challenging the lockdown laws. Legal action was initiated against the curfew and while the curfew is abandoned the action continues in an effort to find it illegal. Further legal action is foreshadowed for compensation due to business and individuals and on the basis the Victorian government has breached its own industrial safety laws.

Beyond all of this, Andrews has orchestrated in Victoria a political fraud on a massive scale — to conceal his own refusal to identify the source of the hotel quarantine decision he set up an inquiry with weak powers headed by a retired judge, Jennifer Coate, a former Family Court of Australia judge, to investigate the issue.

If Andrews were serious then months ago he would have summoned the head of the Premier’s department to his office, instructed him to find out, empowered him with the authority to do so, and given him, say, five days to deliver the written report with associated documents. That’s what any serious prime minister or premier would have done in the circumstances.

Failure to act in this way is the resort to coward’s castle methods. But Andrews wasn’t serious. He chose self-protection, deception and delay. He runs a highly centralised government and is a premier with an authoritarian streak — but he told the people of Victoria he had no idea who took this decision or how it was taken.

And the Victorian public is expected to believe and tolerate such abject abandonment of public duty? This is tragedy turning into farce.

We are witnessing the most elemental torching of ministerial and public service norms supposed to deliver sound government.

What was the former head of the Premier’s department, Chris Eccles, thinking when he appeared before the inquiry to say he didn’t know who took the decision? How could the head of the public service not assume it was his job to find out and inform the official inquiry? What is happening in Victoria? Why are conventions and norms being thrown out?

What is the origin of this institutional sickness, where there appears to be shared denial of knowledge and responsibility? Health minister Jenny Mikakos, who resigned after being slotted with the responsibility by Andrews has repudiated the Premier’s claim and raised a series of questions.

Mikakos said the lack of cabinet process was the “root cause” of the quarantine failure. She said it was “implausible” to suggest nobody took the hotel quarantine decision as opposed to the notion of a “creeping assumption” as advanced by counsel assisting the inquiry.

She urged the inquiry to “critically review the evidence of the Premier and the ministers (none of whom has been cross-examined by those who might be in the best position to contradict them).” Given the inquiry’s lack of coercive powers and initial reluctance to call for the phone records — an action that finally led by the resignation of Eccles for giving false evidence — the issue remains: will the inquiry provide answers or will it succumb, as many institutions have succumbed, as part of Victoria’s institutional crisis?

The royal commission proposed by the Liberals will confront the maladministration and integrity failures, the COVID-19 capability and policy failures, notably in contact tracing along with the hotel quarantine fiasco. But it will materialise only if the Liberals win the next election.

This invites the bigger question: why didn’t Andrews come clean from the start, identify and concede his government’s blunders in relation to hotel quarantine? His refusal to do so has compounded his government’s and Victoria’s difficulties. Yet Andrews may yet escape politically.

One senior Victorian lawyer told Inquirer: “What Andrews is doing is beyond power.” The litigation will play out. But the lockdown will end and pent-up economic demand in Victoria will trigger a strong recovery. That is guaranteed.

The existential question posed by the Andrews government is obvious: what mechanism exists to correct for integrity defects and administrative abuses incorporated into the system and how far does the rot extend?

Our democratic systems are more vulnerable than we appreciate. Correction depends on the operation of the political system through restoration of cabinet and executive norms, parliamentary oversight, judicial action, political party reappraisal and the electoral process. Berejiklian’s fate hangs in the balance but Victoria’s fate is a far deeper and daunting challenge.

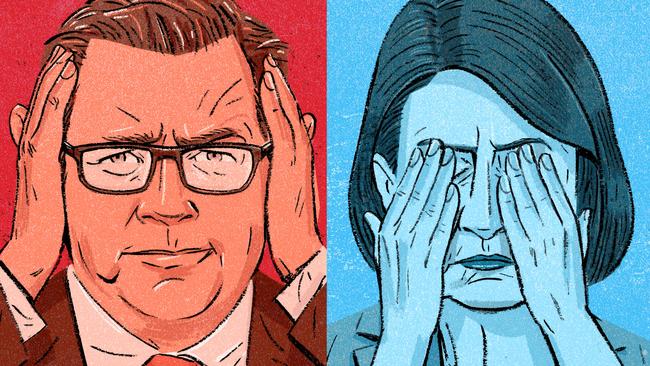

Premiers of the two main states, Gladys Berejiklian in NSW and Daniel Andrews in Victoria, are fighting to survive, yet for completely different reasons their plight raises serious questions about integrity, competence and corruption in Australian politics.