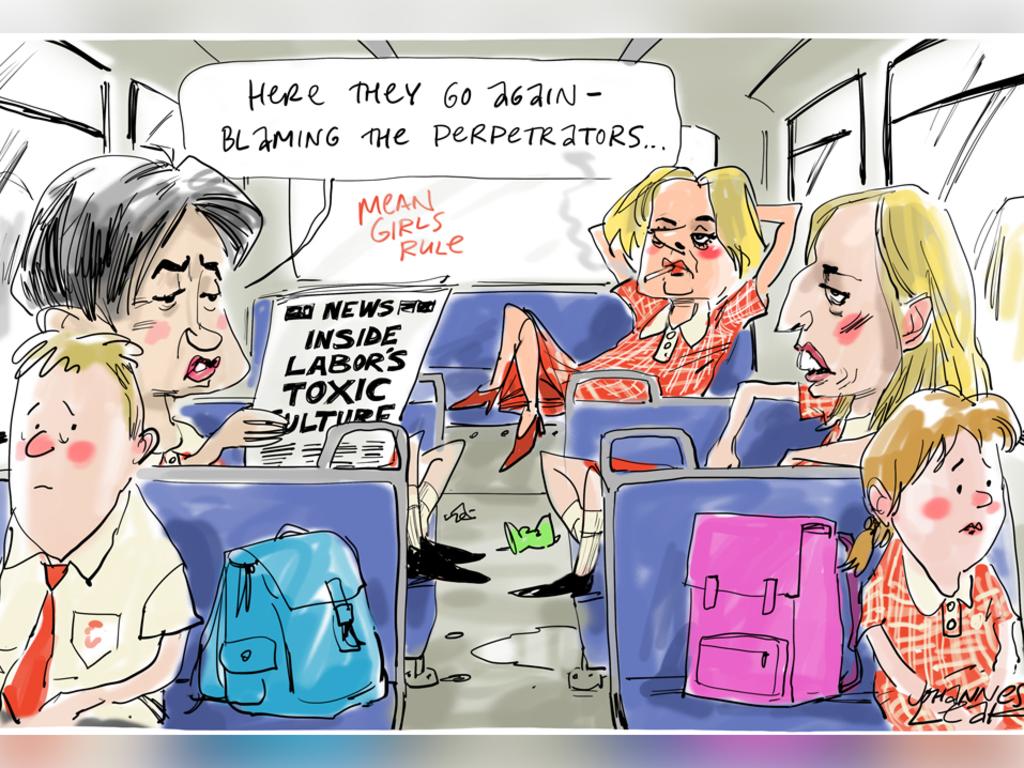

Recent reports about the “mean girl” culture among the Australian Labor Party’s elected members in federal parliament revealed that Wong dismissed a point made by the late senator Kimberley Kitching during a debate about a motion supporting Australian schoolchildren taking part in “civil disobedience” protests at what they considered a “climate emergency”.

Kitching, who died from what is believed to be a heart attack on March 10, thought Labor support for the Greens’ motion to be an overly earnest bid for moral correctness – a piece of theatre, not something of substance. In what was reportedly a “heated” encounter, Kitching suggested many parents would be happier to have their kids in school. “Well, if you had children, you might understand why there is a climate emergency,” a clearly angry Wong apparently responded.

As Sharri Markson reported: “Those close to Kitching say it was particularly hurtful because the painful truth was that Kitching had desperately wanted children, she loved children, but had been unable to have any.”

This notion of children being a prerequisite for policy expertise – and, by extension, ultimately, for leadership positions – has certainly come up over the years.

Then New South Wales opposition leader Peter Collins used to snigger about the childless Bob Carr, claiming it was the “key difference” between the two men.

With the gate open, would-be prime minister John Hewson couldn’t help himself, mocking Carr with the line: “You’ve got to be suspicious about a guy that doesn’t drive, doesn’t like … kids.’’ Presumably, not having children, Carr has bought fewer birthday cakes. But I’ll bet he’d have handled Mike Willesee’s infamous cake questions better on the night Hewson – the architect of the proposed GST – fumbled his way to defeat at the unlosable election.

It took Liberal loudmouth Bill Heffernan to first articulate – if I can bend the meaning of that word – the theory in an interview with The Bulletin published in May 2007. Then senator Heffernan was asked about Julia Gillard, deputy opposition leader at the time, but with polls indicating she would soon be deputy prime minister. Heffernan said Gillard was “deliberately barren” and so unfit for leadership.

He followed up the next day: “If you’re a leader, you’ve got to understand your community. One of the great understandings in a community is family, and the relationship between mums, dads and a bucket of nappies.”

Not many people ever listened to Heffernan, but the Sydney Morning Herald may have been taking notes for an editorial it subsequently published which stated: “(Gillard’s) media persona does not fit the expectations of some voters: a single woman, childless, whose life is dedicated to her career.”

There’s an echo there of the absurd national discussion sparked by The Australian Women’s Weekly 2005 photograph of Gillard in her spartan suburban kitchen with an empty fruit bowl.

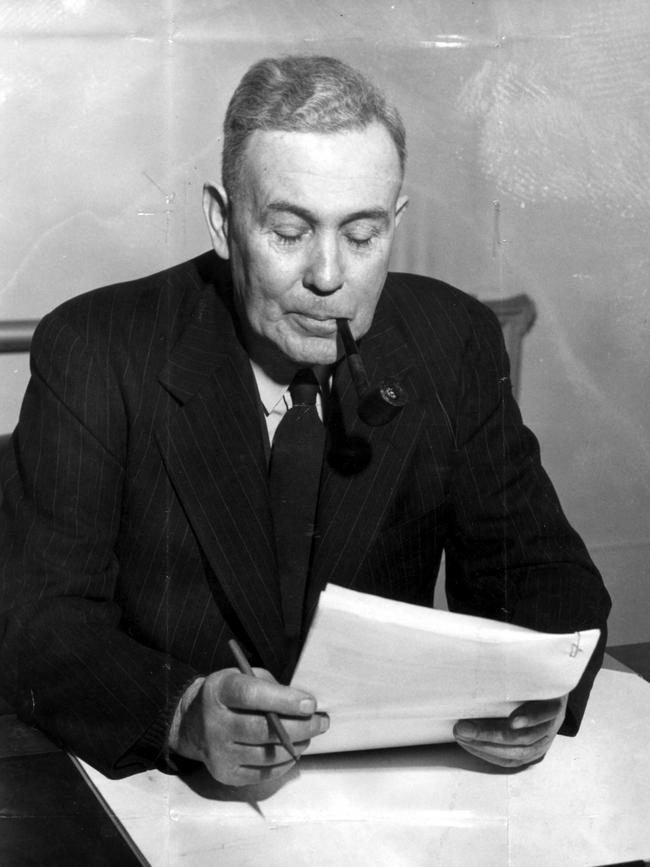

According to the must-have-children rule, Stanley Melbourne Bruce, a successful businessman educated at Cambridge University who was injured at Gallipoli and later in France while winning a Military Cross before returning to Australia and becoming our eighth prime minister, was out of his depth. As must have been Bruce’s successor as prime minister, James Scullin, a brilliant debater who ran a grocery shop in Ballarat as he attended night school to complete the education he had missed out on. He had a terrific grasp of finance and trade but his term as leader was undermined by the suddenness of the Great Depression and Labor disunity.

Nonetheless, acclaimed wartime prime minister John Curtin leaned heavily on Scullin’s advice during his years in Canberra, seemingly untroubled that the Scullins had no children.

Ben Chifley was a humble train driver from Bathurst who had big ideas about what Australia could become. That’s why they appointed him minister for post-war reconstruction. And, as prime minister, he laid plans that would transform the nation in ways he always understood he would not live to see. He had no children to see it either.

World War II alerted Chifley to a couple of our vulnerabilities – Australia needed a much greater population, and the means to feed and support it with affordable power. The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme would link 16 dams with seven power stations through 145km of tunnels under Australia’s most mountainous region, employing 100,000 workers from across the world – the post-war immigration program was his too – and in so doing Chifley created our multicultural future.

John McEwen’s mother died of lung disease when he was two. His dad died of meningitis when he was seven. He left school at just 13, but he’d learned a lot about life.

An industrious, clever fellow, he also attended night school before signing up for WWI. It ended before he could be sent, but he was given 35 hectares outside Shepparton in Victoria anyway as part of the Soldier Settlement Scheme. He knew nothing about the land so worked as a farm hand to find out and went on to establish, across 1200 hectares, one of the country’s premium cattle farms.

He was a federal minister for 25 years during a 36-year stint in parliament and was a champion of the now seldom debated decentralisation despite work-from-home habits suddenly promoting the concept. McEwen always wanted to keep farms in Australian hands and he was opposed to the notion that Australia’s manufacturing should be pushed offshore.

“It would be ridiculous to think that Australia was safe in the long term unless we built up our population and built up our industries,” he said when retiring. It was rural common sense from the man who served as our 18th prime minister, married twice, but had no children.

What do former US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice, former British prime minister Theresa May, recently retired German chancellor Angela Merkel, First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon, retired Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe and French President Emmanuel Macron have in common? They are or were able politicians with all manner of views about climate change. But given no one calls them mum or dad, what would they know?

And this newspaper may need to reconsider publishing those fascinating and insightful columns by the brilliant Bjorn Lomborg, of the Copenhagen Consensus Centre.

He is 57 and still skilfully avoiding children’s school fees.

More than 10 per cent of women never have a child and so, according to Penny Wong (although she appears to have retrospectively taken steps to adjust her position) they would not understand the intricacies of climate change.