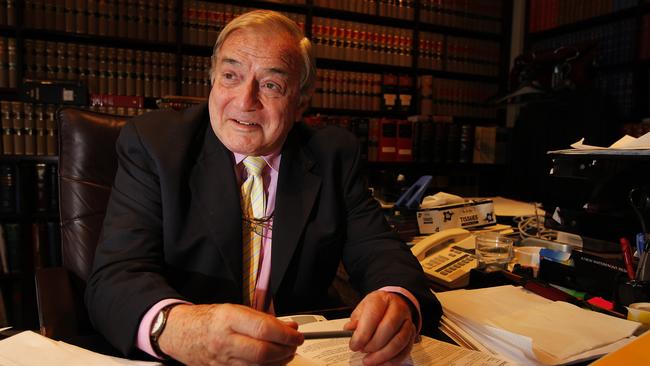

Battle of wills over David Rofe fortune tells a dark morality tale

David Rofe QC relished being the centre of attention. And regardless of any brilliant career as a barrister, left in Rofe’s wake is an almighty mess.

It was Kathy Jackson at her cut-through best as she explained the “real friendship” she formed with a wealthy Sydney barrister, David Rofe QC, in the twilight of his life.

“David and I had a quite different relationship than the rest of, as I call them, the vultures that were hanging around,” Jackson told the NSW Supreme Court.

Vultures? This was the moment when any legal niceties ended, four weeks into a complex probate hearing called to determine how the late Rofe’s $30m estate should be carved up.

Jackson, the former Health Services Union leader who briefly found fame as a corruption whistleblower before encountering a few problems in her own backyard, was highlighting what she regarded as the shameless greed of those who preyed on an elderly man, desperate to grab a share of his wealth when he was most vulnerable, suffering dementia and not far from death.

Although not listed among the 13 warring parties vying for a share of Rofe’s estate in an ugly court showdown that still has several weeks to run, Jackson is a key witness because of her undisputed closeness to Rofe in his last years.

She also has a deep personal interest in this case: Rofe’s last will, signed in December 2014, named Jackson as a co-executor and the beneficiary of a one-tenth share of his estate, or about $3m, plus $100,000 cash.

On the face of it, Jackson stands to inherit instant wealth if that last will is ruled valid. By her own definition, she is not one of the vultures. She is Rofe’s protector, his self-described “day wife” and “companion”. She was also an unofficial “secretary” for a man who could not use a computer. She sent and received his emails, and even typed his last will.

David Rofe died aged 85 in July 2017 from the effects of advanced alcohol-related dementia, leaving behind a vast estate accumulated over decades from his income as a top silk and some wise investments. Rofe had no immediate family and no dependants because he never married and had no children. But the barrister did acquire a disparate collection of relatives, friends, and others whose names were written into — and often out of — many wills he signed in his lifetime. More than three years of private court-supervised mediation since Rofe’s demise was held to reach an agreed settlement on which of Rofe’s wills was valid. Those discussions came to nothing, mainly because of an intractable dispute over Rofe’s last will in particular.

With the battle now being played out in an open court, several of Rofe’s friends have remarked during their evidence that the late silk relished being the centre of attention. He loved the limelight. He loved drama. In death, his life’s highpoints have been well aired in recent weeks but so too have many embarrassing details that he never wanted discussed publicly. And regardless of any brilliant career as a barrister, left in Rofe’s wake is an almighty mess.

Out of dozens of wills Rofe signed in his lifetime, most came after he was diagnosed with dementia in October 2010. Did Rofe have the “capacity” to sign these later wills, and in particular his last will executed in December 2014?

Could Rofe knowingly sign any document with an irreversible illness, when he was often confused and agitated and sometimes did not know who he was? At what point of Rofe’s decline did he become incapable? Was he subjected to any undue influence?

These are the perplexing matters confronting Justice Geoff Lindsay, who is highly experienced in making assessments of capacity based on accepted medical and legal perspectives, yet on this occasion dealing with other complicating factors: conflicting medical reports and swirling allegations of “lies”, “deception”, “theft” and “blackmail”.

The Rofe case, at its heart, is a dark morality tale. No one seems to come out of this story untarnished, but it is surely no one-off.

While the size of the old barrister’s estate might seem unusually large and far outside the realm of normal experience, the debacle provides a rare glimpse into what is surely happening on a wider scale across the nation as larger numbers of fading seniors live longer, at risk of being taken advantage of, but without scrutiny.

One of Rofe’s closest friends, Gregg Hele, will score the biggest payday of any beneficiary if the barrister’s last will is upheld as valid. The December 2014 will hands Hele a two-tenths share of Rofe’s estate, or close to $6m. Hele also scores $100,000 cash.

No one disputes that Hele should benefit handsomely, because his association with Rofe stretches far back in time. As long ago as the mid-1990s, one Rofe will left Hele a one-tenth share. Hele, now 59, has featured in every will since as a significant beneficiary.

During two days of evidence, beamed into the Sydney courtroom via videolink from Victoria where he now lives, Hele confirmed just how close his relationship with Rofe was.

He told the court that he and Rofe were lovers in an “intimate relationship” for nearly 20 years, from the early 1980s to 2000. At the time, Hele helped Rofe as a handyman and gardener and their personal relationship was kept secret. Rofe was most reluctant to be openly homosexual because he feared it could harm his career at the bar. Rofe had a close female friend, Elaine Clark, who regularly drove him home from work and shared TV dinners with him like a couple might. But when Hele was asked if he regarded himself as Rofe’s partner, using modern terms, Hele replied that yes, he did.

In 2000 Hele found another love and drifted out of Rofe’s life, although they remained friends. Hele re-entered the scene again as a central part of Rofe’s existence in July 2014 when he moved into the ailing barrister’s Woollahra home to be his full-time carer, earning $10,000 a month, with two other carers. Hele told the court he “fell back in love” with Rofe as he tucked him into bed at night.

According to Hele, Rofe’s condition improved as he weaned the ageing former silk off alcohol and started an exercise regime. So much so, Hele claimed, that Rofe was almost back to normal lucidity despite experiencing “sundowners” that many dementia patients suffer with confused periods at certain times of the day. Hele insisted that Rofe’s state of mind underwent a recovery, even if he suffered ups and downs. Rofe was definitely capable of signing the December 2014 will, Hele said.

Over many years, another Rofe friend claims to have been very close to the barrister. Nick Llewellyn, self-described as Rofe’s “dependent” and “virtual son”, met him in 2002. He appeared from 2006 onwards in every will and is named in the last to inherit a one-tenth share, plus $100,000.

Hele never liked Llewellyn and referred to him as “Leech”. Llewellyn claimed Hele was jealous. Rofe friends such as barristers John Agius and Anthony Tudehope disliked Llewellyn but it especially puzzled old mate Brendan Hull why Rofe lavished Llewellyn with money when he was otherwise so “mean”. Rofe was so stingy, Hull said, that he gave others recycled Christmas gifts such as a bottle of whisky and hotel shampoo. Arriving at the Hull family’s door for his annual Christmas lunch visit, Rofe would ask to be reimbursed $2 for the Sydney Harbour Bridge toll, claiming he never travelled to the city’s northside except to visit the grave sites of relatives.

Regardless, Rofe paid Llewellyn $10,000 a month for living expenses, plus $6000 a month rent for a Paddington house where Llewellyn lived with his then partner, Curtis. Rofe often paid Llewellyn’s credit card debts. Total funds paid to Llewellyn over the years, estimated to exceed $2.3m, were described as loans repayable on Rofe’s request or death. But all of his wills from 2006 onwards – except for the last one, typed by Jackson, that Llewellyn does not accept – included a provision forgiving the young man all his debts.

When Rofe suffered a serious health breakdown in late 2012 and was admitted to St Vincent’s Hospital, Llewellyn was shut out of Rofe’s life by a group of the old man’s friends who believed he was a bad influence. Depressed and fearing his payments from Rofe would dry up, Llewellyn called for help from someone he believed could save the day: Michael Lawler, formerly a barrister who had worked in Rofe’s chambers years earlier and had known him well. Now employed in a semi-judicial role as vice-president of the Fair Work Commission, Lawler had not kept in regular touch with Rofe, nor was he aware of the barrister’s illness, but he immediately swung into action. Lawler brought in commercial disputes lawyers to intervene in Rofe’s affairs and effectively serve as a buffer between Llewellyn and Rofe friends he called “the nasties”. Six months later, Lawler took a formal role as Rofe’s power of attorney, financial controller and alternate guardian under the auspices of the NSW Guardianship Tribunal.

With Lawler, Llewellyn scored a two-for-one deal. Jackson, Lawler’s partner, also came to Rofe’s aid. Jackson had first met Rofe in May 2012 when he’d offered his barrister services in an ongoing dispute she had with the HSU. That contact was brief because Rofe was forced to withdraw abruptly, confused in court and unable to handle Jackson’s brief. Now Jackson became Rofe’s companion, visiting him at home and lunching with him at Zigolini’s, his favourite local restaurant. She was apparently fascinated by his “war stories” from life at the bar.

When it dawned on Llewellyn that Jackson might have supplanted his role in Rofe’s life, he turned against her and Lawler. The lowest point came in June 2014 when Llewellyn riled up Rofe, telling him that Lawler had acted behind his back, spending $160,000 of Rofe’s money as a deposit for a $1.35m house for Rofe that was coincidentally next door to the Jackson-Lawler residence in Wombarra, south of Sydney. The court this week heard a series of taped phone conversations made by Lawler in which Rofe is heard angrily scolding Lawler, telling him he never wanted the Wombarra property and even accusing his then guardian of being mentally unwell.

Lawler, as he told the probate court, accused Llewellyn of having “undue influence” over Rofe while he was acting in Rofe’s best interests to find the ideal house for him as his dementia worsened. Lawler was adamant that Rofe lacked “capacity” at the time of the Wombarra property purchase. He was equally adamant the old man’s capacity recovered some months later –— sufficient to execute the December will that would be his last. That was the will, coincidentally, that put Lawler’s partner, Jackson, back in line for a $3m payday after a codicil signed by Rofe mid-year, allegedly at Llewellyn’s urging, had effectively wiped Jackson’s inheritance from a March will that first listed her for a one-tenth share. Lawler told the court he insisted the December will should be prepared by an independent solicitor — but Jackson told him that Rofe did not want to engage solicitors. Unlike his position on the Wombarra purchase, Lawler decided this was “not a fight I wanted to have”.

Jackson has attested in her evidence to the Supreme Court that she loved Rofe, did not want his money and never wanted to be in his will. She also confirmed she was determined to carry out Rofe’s wishes, which included serving as an executor for his December 2014 will and accepting whatever inheritance it provided. She’d never done the sums, she said.

Jackson had first appeared in Rofe’s wills less than a year after they met, first with a $45,000 inheritance and then $60,000, before suddenly scoring equal billing with Llewellyn and some Rofe nephews and nieces. In an email, Hele warmly welcomed Jackson to “the tenth club”.

But there was to be a catch. If Jackson was to inherit such instant wealth, as she acknowledged in her court evidence, there was the ticklish matter of her having filed for bankruptcy while Rofe was still alive in 2016. As she confirmed, Jackson’s bankruptcy came ahead of a Federal Court ruling that she owed the HSU $2.4m. Although discharged from bankruptcy in May last year, Jackson confirmed the bankruptcy trustee was likely to reactivate its claim and recoup any inheritance money. That could still leave her with some cash — but depending on how many millions are chewed up in barristers’ fees fighting the probate case. Jackson and Lawler say they no longer live together after separating in February last year.

The undoubted winner out of the estate dispute, no matter what happens, would appear to be Hele.

One Rofe relative, nephew Philip, is in the battle for a share after he was deleted post-2010 from the estate. Hele now disputes his avowed past support for Philip as Rofe’s “closest relative”.

Late this week there were signs that settlement negotiations had resumed outside court. Solicitor Mark Peoples, representing Hele and some pro-Jackson Rofe relatives, was heard loudly telling barrister Raoul Wilson from the opposing side that former Rofe secretary and sometime guardian “Ruth Coleman still gets $60,000, not $30,000”. Another solicitor was heard saying Jackson needed to be included in any settlement. “There’s got to be something for Kathy,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout