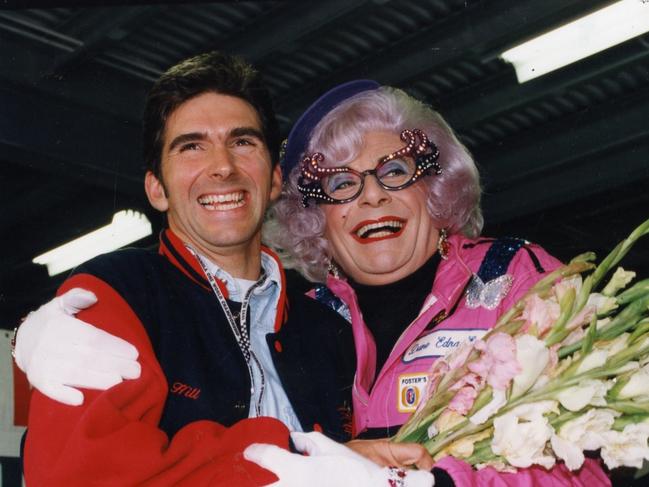

It opened with a classical music theme and was fronted for 11 years by Walton, seated on a floral sofa with her legs crossed demurely, as befitted this sophisticated woman who ran a deportment school for debutantes before launching her TV juggernaut championing the values of elegance.

Walton’s mission was spectacularly derailed in 1976 when her celebrity guest was not Barry Humphries as scheduled but his alter ego Sir Les Patterson. Sir Les arrived on set as a breath of foul air in a powder-blue suit with a visible protrusion in the trousers and a booze-stained orange shirt, slugging repeatedly from a glass of scotch at 9.30am.

“I enjoy the finer things in life and that includes a nice woman and you’re one of my favourites Jaye,” Sir Les began. “I’m a bit of a rough diamond and I think I’m liked for that. I think the reason I’ve risen to the top of the diplomatic tree and represent Australia abroad is not only because I’m a man’s man but also because I’m a dresser. I believe in appearances.

“You get these bastards running around with their open neck shirts and beads hanging out, the Adelaide Festival poofter push, that kind of fella. It’s not for me.

“I believe in representing Australia. I meet people abroad who have never met an Australian before and it’s wonderful to think that they judge Australia by me. It gives me a nice warm feeling and you know where it’s likely to be, that warm feeling, because you give me a warm feeling there as well, Jaye Walton. A touch of bloody elegance, ladies and gentlemen.”

In this freewheeling era of live and local TV, Walton had no choice but to let Patterson hold her and her audience hostage for a full five minutes. “Either these trousers are a bit tight or you’re a bit more attractive than usual Jaye,” Sir Les continued, adjusting his crotch.

Walton’s protege, Adelaide TV and radio legend Jane Reilly, was working in a junior role on the set that day. “Adelaide had never seen anything like it,” she said this week. “The video that exists of it today doesn’t do it justice. It’s had some of the rougher stuff edited out. At one point he looked down at Jaye and asked if she was flashing him a vertical smile.”

The episode epitomised Humphries’ two great loves: his determination to shock and delight audiences by trampling the boundaries of acceptability; and his passion for Adelaide, a city he celebrated in poetry two years ago when he declared he had come to love it more than his Melbourne birthplace.

Humphries first visited Adelaide in 1953 as a 19-year-old member of the Melbourne University Players, appearing in the Welsh play The Wind of Heaven. It was the first time he had ventured anywhere beyond Melbourne and his father paid for him to travel by train on The Overland, during which Humphries fell asleep with his head on a female stranger’s shoulder. When they arrived at the Keswick terminal he asked her: “Did the earth move for you too?”

“On that Adelaide visit there were endless parties with huge consumption of liquor, Turkish cigarettes, Wynvale flagons, Barossa Pearl and a poisonous beverage called Brandivino which was absolutely lethal,” Humphries recalled in a 2020 interview with The Australian. “It was where I first heard the evocative verb ‘to chunder’. It described so well the experiences I had with Brandivino in Adelaide.”

This visit was the beginning of a love affair that lasted a lifetime, cemented around several close friendships including former John Martin’s chairman and philanthropist Sir Edward “Bill” Hayward; musician, gallery owner and monarchist Kym Bonython; and landscape artist David Dridan, who still lives in the picture-book Adelaide Hills town of Strathalbyn.

Dridan told The Australian that Humphries visited him and his wife Sarah every few years, when they would go on painting trips with other artists including John Olsen, Jeffrey Smart and sculptor Silvio Apponyi. “He was my best and oldest friend,” Dridan said. “We were together for 60 years. He was also a very good painter. We used to love going on those painting trips in the desert or the bush or the Coorong. We still have what we call the Barry Humphries bedroom at our cottage.”

The Melbourne Art School-educated Humphries paid tribute to Strathalbyn with his 2013 watercolour of the Strathalbyn Gardens bandstand on the banks of the Angas River. He also offered to spearhead a campaign to euthanise the town’s corella population, which habitually ravages its Norfolk Island pines. “I would ban the corella,” Humphries said in a 2016 interview on FiveAA during his stint as director of the Adelaide Cabaret Festival. “If there was a painless poison I would distribute it in the foliage of Strathalbyn. I am sure I would fall foul of the ratbag conservationists trying to preserve them.”

In an interview with The Australian two years ago after he wrote his poem Ode to Adelaide, he declared Adelaide “the least vandalised Australian city”, saying he no longer ventured into the Melbourne CBD because he lamented the heritage it had lost.

“I suppose I should say Melbourne is my first love in the same way you have to say that you love your parents more than anyone else on this earth,” Humphries said.

“But as any married man knows you can occasionally stray, or at least think about straying. And when I stray, I stray to Adelaide.”

Perhaps because Adelaide is the city that most resembles Australia in the 1950s, Humphries was drawn to its provincialism and parochialism. He loved its strange combination as a town that managed to be prudish and libertine at the same time, saying in his poem that the city “seethes beneath the surface”. As with the development of his many alter egos, where he would identify minuscule aspects of our make-up to tell a greater truth about our national character, he acquired granular knowledge of the wonders and weirdness of the City of Churches.

He had this to say of Hindley St, Adelaide’s sleaze strip, home to the Crazy Horse strip joint and where for many years a statue of Adonis replete with a large concrete penis stood outside the Jules discotheque.

“Hindley St is a nice street that you have let go,” Humphries said. “It has been delivered gift-wrapped to what I think Edna would call ‘an element’ … Even I, a black belt in karate, a fact seldom known, hesitate to walk it at night. But Les would be drawn to it. He liked Melbourne St in North Adelaide very much because it had the first adult shop in Australia. Adelaide was a pioneer of the pink-lit emporium, selling items tastefully wrapped for gentlemen, and sometimes even for ladies dressed as gentlemen.”

On the burghers of North Adelaide, Humphries hailed their elitism as without peer in Australia. “Dame Edna really does like North Adelaide because it’s so refined,” he said. “There’s a kind of superiority, a kind of snobbishness in Adelaide that’s unknown in the rest of Australia. And I’m all for snobbery. I’m a great believer in elitism. I believe quite genuinely that some of us are better than others. It’s a good thing that excellence and intellectual superiority are rewarded.”

Another of Humphries’ great Adelaide friends was Bill Muirhead, the Saatchi & Saatchi ad man and former agent general for South Australia in London. It was Muirhead who arranged for Humphries to be filmed reciting his Ode to Adelaide at South Australia House in London in 2020. Muirhead told The Australian this week that the poem was a reworking of one Humphries wrote years earlier but lost. The original contained the lines “When I get the first-night jitters, I always reach for Haighs and Ditters”, in reference to the iconic Adelaide chocolate and nut brands.

When the new version was written, Muirhead achieved a rare feat with an artist who always railed against censorship, as Humphries politely accepted the agent general’s request to delete the line declaring Adelaide had “very good wines and wonderful crimes”. “Barry loved SA,” Muirhead told The Australian. “He would always say Adelaide audiences are the best in the world. He was a foul-weather friend. He was a generous friend. He performed some wonderful cameos at the South Australia Club events in London. That made the club very popular and the membership much sought after. At one of the annual South Australia Club dinners he did a whole performance as ‘Barry’.

“He taught us Australians how to laugh at ourselves. It seems that some of his detractors weren’t blessed with that ability.”

Mercifully, Adelaide is displaying none of the hand-wringing priggishness to which Muirhead alludes, as epitomised by those humourless souls who run the misleadingly titled Melbourne International Comedy Festival.

Plans are afoot in Adelaide to commemorate Humphries at his beloved stomping ground, Her Majesty’s Theatre in Grote St, where he was made patron during its stunning $66m redevelopment in 2017, with one idea being to rename the neighbouring street from Pitt St to Humphries Lane.

One of the nicest tributes this week came via Dridan’s wife, Sarah, who had this to say to The Australian: “Whoever Barry was talking to, he was totally with them. It didn’t matter if you were young or old, a dignitary or a waiter, he was always with you. You had him all to yourself.”

And while Walton is no longer with us, there is a chance that right now she has been approached in the hereafter by a bloke called Sir Les, bringing a touch of elegance to things by adjusting his pants and talking about his warm feeling.

David Penberthy is the South Australia correspondent and co-host of Adelaide’s FiveAA Breakfast Show.

For Adelaide housewives in the 1970s, Touch of Elegance was appointment morning television, where former model Jaye Walton combined light interviews with visiting celebrities with infomercials for frock shops and hair salons.