Banks must work to avoid risk of a financial meltdown

The GFC revealed how difficult even modest reforms are in the face of the most powerful vested interest. Only a cataclysmic crisis is likely to change that.

Higher interest rates were hurting the financial system and risked causing another financial crisis, the argument went.

Never mind that finance students are typically taught how higher interest rates tend to increase bank profitability because they tend to boost banks’ net interest margins (the difference between what they pay on deposits and earn on their assets).

If the return of interest rates from zero to more normal levels throughout the developed world is actually a problem for the financial system, then it is that system that is self-evidently not fit for purpose, despite the array of “tough” post-financial crisis rules that have been trumpeted by regulators for the past decade.

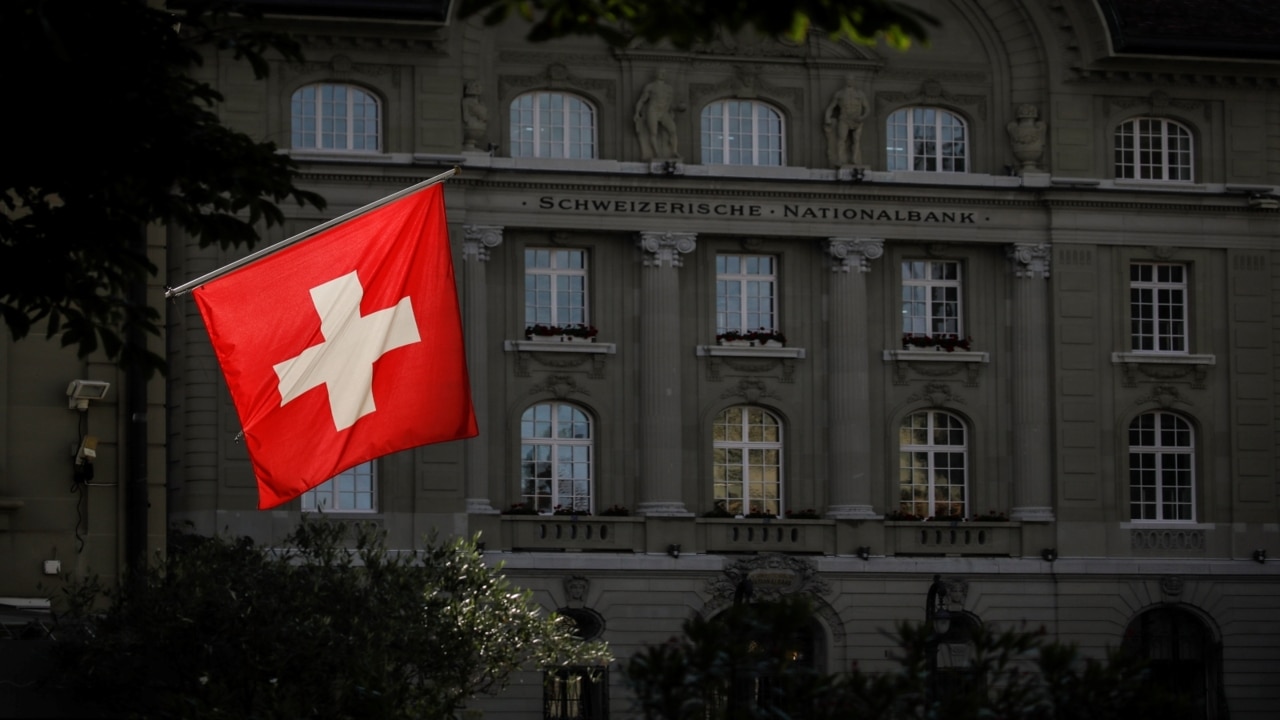

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, First Republic and Signature in the US (all mid-sized banks, around half the size of ANZ or Westpac) and the demise of Credit Suisse in Europe were caused by wholly different factors, but all were a humiliation for regulators.

Their failure shouldn’t be a signal for central banks to step back from their core task of returning inflation to about 2 per cent, but rather a welcome reminder that fundamental reform of the financial system, in the interest of the public, not the system itself, should be high on the to-do list.

“A good analogy is that banks were going 97 miles an hour in a residential area (before the GFC), and now they are going 94 miles; it’s not a meaningful change,” Anat Admati, Stanford professor of finance and a global authority on bank regulation, tells Inquirer.

Credit Suisse had been floundering for years, bogged down in corruption scandals, including charges for aiding cocaine smugglers. Its shares had declined by about 70 per cent before the Swiss government encouraged rival UBS to buy it last week.

The three American banks failed in large part because their assets dropped significantly, prompting concerned depositors to start running for the doors. What’s shocking is US regulators, who have designated staff for every US bank, didn’t act and left it to depositors to sound the alarm, sending a minor tremor throughout financial markets.

Indeed, SVB was insolvent for a year, having no meaningful equity.

For now, all is quiet on the financial front.

In his press conference this week, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell calmed financial markets, cautiously lifting the US benchmark interest rate another 0.25 percentage points to 5 per cent and declaring the US financial system was “sound and resilient”.

But it’s critical to judge central banks by what they do, not what they say. Regulators will always say their banking system is stable – anything else would be an admission of incompetence.

The Reserve Bank has just declared Australia’s banks are “unquestionably strong”. They are, until they aren’t. Australia’s banks remain highly leveraged, about 20 times (in other words they support $100 of assets with around $5 of equity and $95 of debt), vastly more than any prudent financial institution was in earlier times. That means even small declines in the value of bank assets can wipe out their sliver of shareholders’ funds.

Credit Suisse passed its Federal Reserve stress test with flying colours last year.

The response of regulators in the US to the mini-crisis – providing massive new liquidity lines to banks, and in effect guaranteeing all deposits in the US financial system on a whim – smacked of panic, confirming fears of independent financial experts who worry we keep kicking the can down the road.

“Many banks in the US cannot survive in free markets and are kept alive only by guarantees and subsidies,” Admati says, pointing out that the latest bout of problems was reminiscent of the savings and loan crisis in the US in the 1980s, when smaller institutions similarly collapsed en masse as interest rates surged.

“Many insolvent institutions were allowed to persist. Everyone pretended they were OK and they didn’t default, but meanwhile they were incredibly reckless and ultimately collapsed and caused much harm,” she recalls.

When interest rates increase, the market value of bonds and home loans with fixed interest declines. That’s an iron law of finance and shouldn’t have been a surprise to the directors of any of the three American banks that failed.

What’s especially worrying is these aren’t the only banks to have ignored basic risk management. The mini-crisis this month could well be a harbinger of a more serious crisis in the near future unless governments realise their banking systems are still not fit for purpose.

The market value of US bank assets is now a whopping $US2 trillion ($2.98 trillion) lower than the book value of the assets on their balance sheet because of the increase in interest rates during the past 12 months, according to an excellent piece of research published last week by four economists at Stanford, Columbia and other top US universities.

“We note that these losses amount to a stunning 96 per cent of the pre-interest rate tightening aggregate bank capitalisation,” the authors found.

In other words, almost all the capital in the US bank system, based on mark-to-market valuations, has been wiped out.

The researchers found about 10 per cent of the 4800-odd US banks were sitting on even worse unrecognised losses than SVB had, and 10 per cent had a worse level of capitalisation (the level of equity in relation to total assets).

The 5 per cent of US banks with the worst losses have experienced a 20 per cent drop on average in the value of their assets.

“If SVB failed because of its losses alone, more than 500 other banks should also have failed,” the researchers concludes.

SVB stood out because 78 per cent of its assets were funded by uninsured deposits, a much higher proportion than most US banks, where uninsured deposits make up about 23 per cent of the total.

US regulators, as in Australia, guarantee the first $US250,000 of deposits, giving most Americans confidence they don’t need to rush for the doors if their bank becomes insolvent.

“Even if only half of uninsured depositors decide to withdraw, almost 190 banks are at a potential risk of impairment … with potentially $US300bn of insured deposits at risk,” the study worryingly concludes.

Kevin Hassett, chairman of the US Council of Economic Advisers under president Donald Trump, is less pessimistic about the US banking system but nevertheless anticipates a recession as the Fed presses on with higher interest rates.

“SVB had terrible interest rate exposure that made it an outlier among American banks. Signature was apparently, and bizarrely, shut down because someone at the FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Commission) was nervous about their exposure to crypto. In addition, the Fed has pumped an enormous amount of liquidity into the market,” he tells Inquirer.

Hassett puts the seeming resilience of the US economy – it has defied doomsayers for the past year – down to “heavy consumer borrowing and leftover savings from the enormous Covid stimulus”.

“Most of the data are turning sharply south now, though, the only patch of sunshine is the labour market, but it tends to be a lagging indicator,” Hassett says, predicting the US central bank will need to lift its benchmark rate well beyond 6 per cent, the current level of consumer price inflation for the year to February.

“When the Fed gets the federal funds rate above the inflation rate, we will be headed in the correct direction and, given the slowdown in activity, it might not need to up much more to accomplish that.”

Billionaire hedge fund manager Ken Griffin observed this month that the Fed’s response reflected “capitalism breaking down before our eyes”.

“Unlimited deposit insurance is a very dangerous situation; more people will be doing what they are doing now,” Admati says, referring to the fact, for bank managers, it can pay to be negligent under the current regime.

By tearing up the rule book on deposit insurance, the Fed has entered uncharted waters. Total deposits in US banks amount to about $US18 trillion, but the FDIC’s insurance fund amounts to only about $US130bn. A more widespread run on deposits would be an unmitigated financial and fiscal disaster.

The modern financial system is the antithesis of a free market, where the upside of having a banking licence is retained by bank management and shareholders, while the large periodic downsides are borne by the taxpayer and the rest of the society.

“The focus should be prevention instead of a cure in the form of bailouts,” says Admati.

Many solutions have been proposed through the years to make banking less of an ulcer on the real economy.

For a start, banks should be forced to include the value of government bonds in determining how much equity they should maintain.

Incredibly, government bonds, whose decline in value has caused this mini-crisis, still attract only a zero-risk weight – not 50 per cent, zero!

More generally, as Admati has argued powerfully in her 2014 book, The Bankers’ New Clothes, banks should be required to reduce their leverage from the 20 or 30-odd times considered acceptable to something closer to 10 times. That would make insolvency more difficult, even in a serious crisis.

Sure, it would reduce rates of return in banking (and the bonus pool), but so what?

Alternatively, why not let citizens hold their bank account at the central bank and make payments to each other over those accounts? That would remove the payments system – a public good – from the clutches of excessive risk-taking.

Commercial banks are allowed to hold accounts there, so why not ordinary people?

Henry Ford was right when he said people would revolt if they understood how banking actually worked.

Until they do, there is, sadly, little hope for sensible reform. The global financial crisis revealed how difficult even modest reforms are in the face of the most powerful vested interest, Wall Street and its equivalents throughout the developed world. Only a cataclysmic crisis is likely to change that.

The sudden collapse of three US banks earlier this month ahead of the demise of the once-venerable Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse has prompted worried calls for central banks to back off in their quest to stamp out inflation.