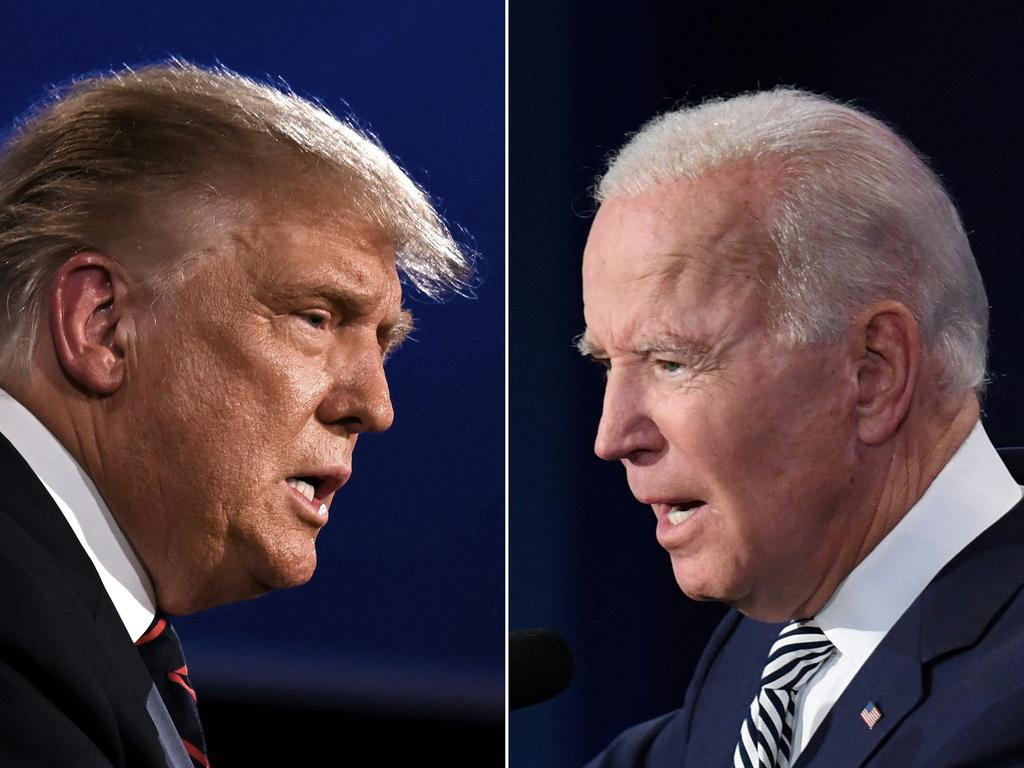

Australia’s future is at stake in the US election

The US unipolar moment is over and a transition to a new global order is under way. Trump’s victory in 2016 was just a symptom.

Australia has a lot at stake in who wins the looming American presidential election. Donald Trump or Joe Biden, the US unipolar moment is over and a transition to a new global order is under way. Trump’s victory in 2016 was a symptom of this shift in world affairs, not its cause.

While his idiosyncrasies have disconcerted many people, they have dramatised the basic reality. Consequently, Australia is having to seriously rethink its national security assumptions and planning. That debate, well under way by 2016, intensified in 2020.

Should Trump be re-elected, the consequences could be cascading. Should Biden win, his administration will face major challenges in rethinking American commitments and alliance structures. It will not have the option of simply making some grandiose declaration that America is “ready to lead again”.

Its leadership has been all but forfeited by Trump, is under direct challenge from China and Russia and needs fundamental institutional rebalancing, if it is to underpin a viable global order in the 2020s.

The September/October issue of the great journal of the Council on Foreign Relations, Foreign Affairs, was devoted to “the world Trump made” and offers a rich mix of opinions as to what might come down the proverbial pike over the next four years, pending the outcome of the presidential election. Its longtime editor Gideon Rose, in his preface to the issue, declares forthrightly that Trump has trashed the old order and that “one thing many of Trump’s domestic supporters and critics agree on is there’s no going back”.

Ben Rhodes, who contributes an incisive essay to the issue, hopes to see a major Democratic rethink and revival. But he begins with the premise that “the liberal international order is defunct. We need a new one”. A longtime confidant of Barack Obama, he authored a book in 2018 called The World As It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House, in which he attempted to grapple with the geopolitical and geo-economic head winds that were blowing even before Trump stunned many of us by winning the presidency in 2016.

The implications for Australia of this epochal shift are considerable and the debate about them has, for some considerable time, centred on what ANU emeritus professor Hugh White dubbed “the China choice” — the notion that we had, in the early 21st century, found ourselves stranded between the US as our major security partner and China as our biggest trading partner. That apparent dilemma became steadily more acute in the 2010s and seems likely to become very serious in the 2020s — especially should Donald Trump be re-elected.

This has led a body of opinion in this country to espouse the view that China is set to displace the US in East Asia and perhaps far more widely as the number one economic and, in time, military power in the world. We no longer have a realistic choice but to understand and work with this immense change in our strategic circumstances, they declare. Our former ambassador to China, Geoff Raby, in his new book, hammers this home, writing of what he calls “Australia’s dystopian future”, while arguing China is a “bound Prometheus” and will not directly threaten Australian security.

There are two crucial flaws in his argument. He concedes openly that China, under Xi Jinping, is a mercantilist, revisionist and totalitarian power, but thinks it is not a threat to us, because its dependency on resource imports and export markets are a “nightmare” for its strategic planners. Stunningly, he fails to grasp that this is precisely why China is so rapidly building up its naval and expeditionary power and Xi is talking up the importance of readiness for war. Our reasons for concern about all this are palpable.

The second flaw in his position is that it is too binary. He sees Sino-American rivalry, but dismisses the significance of other major players. In particular, he is wedded to the “Asia-Pacific” when the strategic and economic reality is the Indo-Pacific — from the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea. Rory Medcalf, of the National Security College at ANU, rebalances all this in his early 2020 book, Contest for the Indo-Pacific: Why China Won’t Map the Future.

Medcalf both surveys the growth, stances and interests of multiple powers, from India to Japan, including Indonesia and Vietnam and argues that China both can and very probably will be constrained — but that a new order will have to be built to keep the peace. Australia can and ought be a proactive player in seeking and designing such an order, he insists.

It’s important in such a context, to do a stocktake regarding world order. The very idea of a more or less ruled-governed international order of states is “Western” (European) in origin. It is generally dated from the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), which is seen as having been buttressed or modified successively by international conferences at Utrecht, Vienna, Versailles and Paris, between 1713 and 1990.

Westphalia is hailed as the origin of the very idea of international law and an international geopolitical order, but it was a wholly European design. There was, in 1648, no United States; the Ottoman, Mughal and Qing empires were all in place (the last of them only just); Russia was just beginning its epic march into Siberia and Central Asia; Australia had only a few decades before been stumbled upon by the Dutch. Its colonisation by the British was a hundred and forty years away.

The Congress of Vienna was, again, wholly European in focus and the Concert of Powers it created was not something that contemplated the non-European powers having much relevance to “world order”. Even at Versailles, in 1919, the European powers and the US paid scant regard to the peoples of the non-Western world.

Even now, the UN Security Council notoriously reflects the old Eurocentric world order, with four Western powers and China, but not Japan, India, Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria or Indonesia. What we are now confronting is the long-postponed and seriously complex task of creating an institutional order for the 21st century that finally integrates all nation-states into a global system of rules within which they think they can operate. China’s sheer weight and mass mean this issue cannot be postponed any longer.

The challenge is to effect that reform without either a major war or a disastrous regression in the kind of order that prevails. A crucial consideration is that China may already have peaked and, under Xi, may be seeking to capitalise on its perceived window of opportunity before it becomes hemmed in by a coalition of other states eager to constrain it. Talking of “peak China”, however, is a little like talk of “peak oil” back in 2004. In fact, there is now an overabundance of oil and if we shift from its use it will not be because we have run out of it.

Innovation in energy technologies, as in many other fields, is occurring at a dizzying pace. China is seeking to transform itself into a gigantic hub of innovation. It may or may not succeed, but it does mean it will have to confront — by more imaginative and flexible means than repression — the need for institutional reforms that will bring political innovation to the party-state. That will have many implications for international trade and geopolitics. The best Chinese thinkers, many of them in the diaspora, are hard at work thinking through these issues. Jiwei Ci’s Democracy in China: The Coming Crisis (2019) should be required reading in this context.

A generation ago, the American scholar of constitutional law and geopolitical strategy, Philip Bobbitt, wrote a remarkable book called The Shield of Achilles, which has been unduly neglected and even disparaged on account of its size and difficulty. Its conceptual relevance is growing as the constitutional order of nation-states that prevailed in the 20th century starts to come apart and the need for a fundamental rethinking of international order becomes ever more apparent.

Bobbitt’s argument, in brief, was that each successive international order had marked and legitimised a new evolution in the nature of the state, rather than simply a restoration of order between states. The driver was the impact of technological innovation in the instruments of war and commerce on both relations between subjects and rulers and those between rivalrous states.

Bobbitt anticipated what he called a mutation of “nation-states” into “market states”, by which he meant states necessarily geared to vast transnational transactions and trade flows, vulnerable to global movements of capital, ideas and risks to the commons and cosmopolitan commitments among its elites, as well as exposure of its masses to all these things. Such developments, he argued, would increasingly alter the specific challenges states face, as well as the plausible means for meeting those challenges. This would end up having transformative implications for the international order among states.

You wouldn’t gather any of this by following the low-grade debates between the US presidential candidates for the upcoming election. But this is the deep background to the tectonic shifts and uncertainties with which we have been grappling since the end of the Cold War.

Both China and the US, each in its inimitable way, are confronting all this. Bobbitt would say that they are different kinds of nascent market state (mercantile and entrepreneurial, respectively) and each is straining to cope with the challenges confronting its nation-state constitution. If the competition between them fails to address the underlying drivers, it could end in a disastrous meltdown of order and open conflict.

Australia, like every state, each in its own way, is caught in these cross-currents. The whole Indo-Pacific is undergoing immense and roiling transformation. The clear challenges before us are to grasp the nature of the challenge, to build relationships with other states grounded in a growing comprehension of that challenge, and to balance China’s growing power not as America’s “deputy sheriff”, but as a responsible and proactive middle power.

This has been a difficult proposition under Trump and would likely be even more so should he win on Tuesday. Should Biden win, the core challenges would remain, but steadiness, coherence and reliability would be more likely to come back into US grand strategy. His list of proposals is all about international challenges and the need for the renovation of American democracy. He doesn’t use Bobbitt’s language or have his sweeping conceptual vision, but the logic of the case he makes points to those things. We have a lot at stake in the choices Americans make, but we have choices of our own to make. They are important, they are rooted in the same fundamental challenges and they are ours to make.

Crucially, they do not, as Medcalf has shown, with exquisite attention to detail, hinge on a binary choice between alignment with the US or subordination to China. They hinge, rather, on our willingness to engage with a wide range of partners and neighbours in both imagining and creating mutual understandings, pragmatic and prudent coalitions and viable, innovative institutions that will enable us to navigate the turbulent waters in which we now find ourselves.

We have learned, since 2016, that America cannot be taken for granted. We have learned in 2020, that China can be a bully. But the Indo-Pacific is a vast domain and we can thrive in it.

Paul Monk is the author of Thunder From the Silent Zone: Rethinking China (2005) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018), among other books.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout