Australia’s defence strategy must be focused on China, China, China

We are wasting billions on capabilities irrelevant to our biggest threat — China — and what should be an asymmetric strategy. And that’s not even the most ludicrous, frankly surreal element.

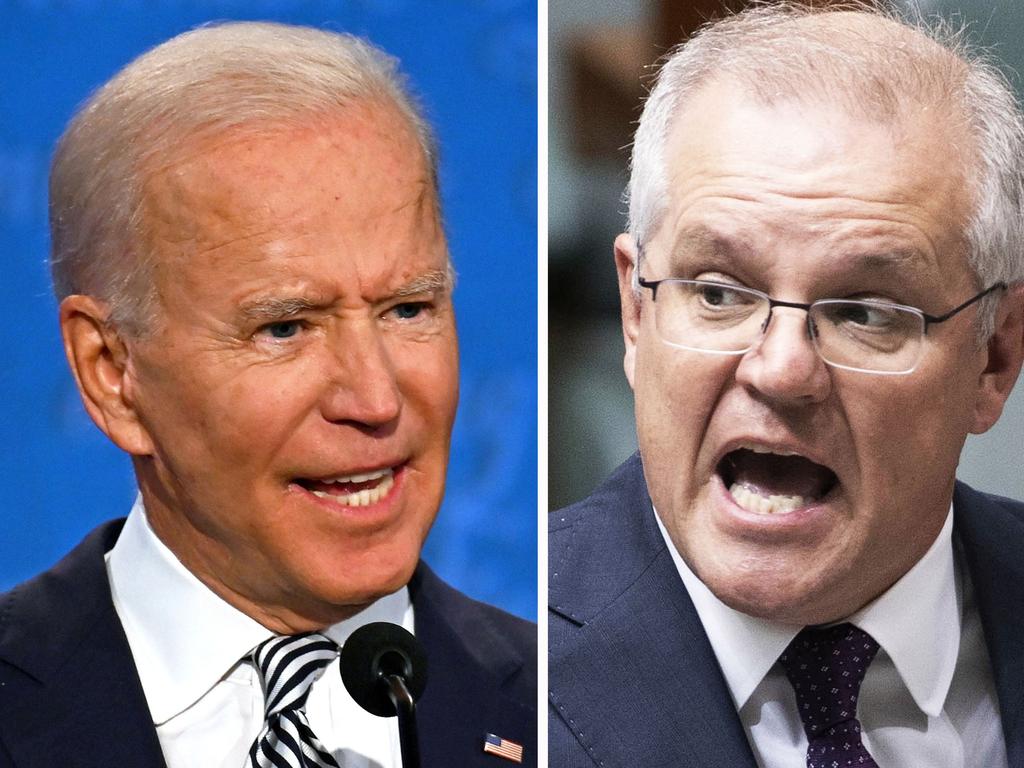

Scott Morrison and Defence Minister Peter Dutton are leading a move away from the old paradigm, but it is too slow, and too little.

Everything tells us our strategic circumstances have changed gravely for the worse, because of China’s new capabilities and new aggressiveness. But we are still muddling along with the old defence force structure underpinned by the old assumptions.

This is potentially deadly.

To put it at its plainest, we are continuing to pursue “a balanced force” when we urgently need to switch to an asymmetric approach which would impose massive costs on an aggressor.

We have just emerged from one of the most intense weeks of prime ministerial diplomacy in our history. Everywhere, the message was clear: China, China, China. The G7 summit called for a new inquiry into the origins of Covid; called out Beijing for its unfair trade practices; condemned its human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and throughout China; supported “a free and open Indo-Pacific”; and warned Beijing against using force on Taiwan.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, standing next to Morrison, said: “I think people are worried about what’s happening to the Uighurs … about the general repression of liberties in Hong Kong and some of the ways China behaves in the region, particularly towards Australia. That’s one of the reasons we’re sending the (Royal Navy) Carrier Strike Group your way.”

The Brussels NATO summit vowed to confront Beijing’s “systemic challenges”. NATO secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg said: “We are concerned by China’s coercive policies.”

Morrison, in an important speech, said: “Australia’s strategic environment has changed significantly over recent years. Accelerating trends are working against our interests … The view that the world hasn’t changed in the past five years is disconnected from reality.”

But what has not changed in the past five years is our defence strategy. The underlying strategy hasn’t altered in 50 years. We are slowly building a bigger defence force, but based on all the same assumptions as before. These assumptions are now wrong, and as a result we are wasting tens of billions of dollars on irrelevant capabilities and neglecting vital things we should and could do.

This is best expressed by Ross Babbage, the grand old man of strategic policy. He tells Inquirer: “This idea of a generalised force, a balanced force, is based on very general thinking. Defence used to say we don’t know what the future threats are, so we need a bit of everything – which meant they didn’t do anything particularly well. That has been the culture for decades. There’s a whole habit of thinking based on the idea of no particular threat.

“But now we do know the identity of the primary serious threat, the nature of its forces, the goals of its national leadership. There is a need for a much more focused, and much faster, system of defence force development.”

Three developments have changed everything. China has had a massive military build-up and is now more aggressive internationally than at any time in its modern history. The US is still critical, but after Donald Trump’s repeated verbal trashing of alliances and Joe Biden ruling a Democratic Party in which the anti-military left is resurgent, and given toxic US internal division, the absolute reliability of the Americans is less clear. And our region is bristling with military capabilities.

There is one strategic threat to Australia: China. All our defence efforts should be directed at countering that threat. Everything else Defence does is not only second order, but trivial, because it deals with contingencies that cannot rise to a serious direct threat.

We could take a lesson from China itself. In 1996, Beijing was bullying Taiwan to coerce an election. The US sailed two aircraft carrier battle groups into waters near Taiwan and calmed everything down.

Beijing determined that this would never happen again. It junked its “people’s war” doctrines and engaged in a single-minded pursuit of asymmetric capabilities designed to raise the cost to the US of any action near Chinese waters. Beijing realised it would be many, many decades before it could ever match the US globally. Asymmetry was its salvation. Asymmetry simply means a weaker military power using weapons which don’t cost it very much to wreak huge, unacceptable damage on a much bigger military power. The key was missiles. Beijing produced thousands and thousands of missiles which can hit US assets, especially expensive platforms like aircraft carriers.

Australia needs to adopt the same strategy towards China. We spend $45bn a year on defence but have a ludicrously small force of just 60,000 full-time service people and no strategic weight in any one area, no ability to sustain prolonged combat operations at all. We cannot possibly develop strategic mass across the board, so we should develop it in the key areas where we might have to fight.

We will pay a 20 per cent cost premium to build our navy at home. I think that’s justified because it delivers sovereign capability, it delivers technological uplift in the whole economy – and without money and jobs in Australia, these giant defence projects become politically unsustainable.

Beyond that we are wasting billions of dollars on capabilities irrelevant to the maritime threat and what should be our asymmetric strategy. The most ludicrous, frankly surreal element of this is the $30bn we plan to spend on armoured fighting vehicles. ASPI’s Marcus Hellyer lists them in The Cost of Defence: 450 heavily armoured Infantry Fighting Vehicles, 75 tanks, 211 Boxer combat reconnaissance vehicles, 47 combat engineering vehicles, and 90 self-propelled howitzers and their resupply vehicles.

Hellyer says this will cost between $30bn and $42bn over the next decade. Forget the submarines. They might be later than we want and more expensive, but they will be good subs eventually and they are wholly relevant to our security needs.

But these armoured vehicles are perfectly designed to make up for all the shortcomings we discovered in our Afghanistan and Iraq deployments. If we faced no serious threat to ourselves, if we had an infinite amount of money and if we planned to spend the future deploying our tiny army into Afghanistan and Iraq, these expenditures would make sense. But in the real world in which we live, these expenditures are as close to insane as you can imagine. There is half a case for having 50-odd armoured vehicles in case some very eccentric problem arose on a Pacific island, one with very good roads, where they might be relevant.

But 90 per cent of this expenditure, tens of billions of dollars, has absolutely nothing to do with our core threat, core task, core necessity.

The defence leadership at the non-political level has not remotely internalised our new threat environment. Bits and pieces have been added to our capabilities which nod towards our maritime situation, but the core force structure and expenditure pattern sails serenely on as though nothing has changed. In Morrison’s terms, it is “disconnected from reality”.

Much of the non-political defence leadership continues to believe in three propositions which are now plainly false: that answering completely remote and unlikely ground contingencies is of equal importance to dealing with the immense difficulties caused by Beijing in our maritime environment; that because China is a superpower there is nothing meaningful we can do anyway; and that the US will always take care of business.

We continue to design the ADF to deal with past situations under past assumptions. We built our two huge LHD ships because we were embarrassed in East Timor not to have suitable troop transports. But the doctrine we developed around them, that we could escort thousands of troops into hostile environments with the transport ships protected by our Air Warfare Destroyers, is completely obsolete.

We could not escort such ships against Chinese missiles. In any event, there is no conceivable destination for them that is of any relevance in a potential maritime conflict. And our tiny army is too small ever to have a strategic effect.

The army can play a significant role in maritime strategy. The US marines, which the ADF sometimes resembles, has decided to get rid of its tanks and emphasise small naval craft which can take teams of marines with all kinds of missiles – shooters as they say – to all kinds of destinations.

The whole of the US defence establishment is coming to realise that to counter Beijing’s asymmetric missile-centric strategy, it needs lots more shooters dispersed into lots more locations.

The Australian army should get longer-range missiles which it can carry and deploy wherever it likes, including to our own coasts, which can make it a supplement to the navy and air force achieving dominance in our air and sea approaches. This can have an offensive capacity as well because such small, relatively covert teams could even, in plausible circumstances, be deployed at hot moments in different spots around the region.

There is money for this in the defence budget but it is the tiniest add-on to an armoured structure which is just nuts. To put it impolitely, the Afghanistan experience has completely buggered the army’s structure. As Hellyer comments, the new structure “requires all three (army) brigades to have an armoured cavalry regiment with tanks and heavy cavalry vehicles as well as infantry battalions with (40-tonne) Infantry Fighting Vehicles – an example of how a previous deployment can drive enormous cost implications into future programs and plans”.

As numerous political and military leaders have warned us, there is every prospect of a real security emergency – indeed of outright military conflict – in our region over the next six to 10 years. And yet our new submarines and our new frigates don’t get here until the 2030s. The one quality Defence screamingly lacks more than anything else is urgency. It operates with that same sense of immediacy and speed which the Vatican took (I love both the Vatican and Defence, so can speak honestly about each) in reversing its view of Galileo.

The government’s Defence Strategic Update made the stark case that we lack any long-range strike capacity to deter any enemy, and keep it far from our shores. We have made token gestures towards doing something about this, such as announcing the acquisition of 250 long-range anti-ship missiles.

But missiles are at the centre of all modern warfare. One of the government’s very best initiatives was the announcement, fully a year ago, that it would create a sovereign guided weapons capacity in Australia. That means a missile factory. The idea is simple, clean and brilliant – and it is such a good idea that Morrison re-announced it in March and Dutton has recently spoken of it in parliament.

The rationale is compelling. We must acquire strike capacity through long-range missiles. We plan to spend more than $90bn on missiles for our ships and subs and planes, and now for some ground-based missiles as well, over the next 10 years.

Therefore, let’s find a big American company, partner with them and make a lot of missiles, primarily for ourselves but hopefully also as part of the US supply chain. That way we can make enough missiles to have a war-fighting capability, and we can have some control over when we get them. We can continue to make them even if in some contingency our allies need all their missiles for themselves.

But to hear Defence officials discuss this in recent Senate estimates was dismaying. After a year, they are at initial planning stages. They may not just have one partner, as the PM announced, but lots of partners for lots of different bits and pieces. Instead of a simple, clean project Defence, in its normal way, is going to transform this into a giant science experiment with a million moving parts.

After a decade’s deliberation, they may come back with a terrific Icelandic/Ecuadorean hybrid Australian part-designed orphan missile, a bargain at 20 times the cost of anything else, for which there will be no customers. The missile equation is urgent. The way Morrison spoke in March, and Dutton more recently in parliament, suggests that they know this. They should remember the Defence Department works for the government, not the other way around, and they should order a result, and a commencement of facility construction, soon – within months, or weeks.

The old ways were never much good. They are absolute rubbish now.

Australia is following the wrong defence strategy. It is a mistake of perhaps mortal consequence. It involves a profound misreading of our national circumstances, and the continuation of old policies and old habits of thinking which are no longer relevant.