Australia yet to lead the charge on electric vehicles

Electric vehicles are coming, but not as quickly as Labor would like.

It’s been two years since Australia stopped making cars but somewhere in our psyche we’re still singing “Meat pies, kangaroos and Holden cars”.

Or perhaps that should now be “kale shakes, kangaroos and battery cars”, after suggestions this week that the industry could be revived to make electric vehicles — in line with the Labor Party’s vision that half of us will be buying them in 10 years.

After Holden closed down, one industrialist, Sanjeev Gupta of industrial giant GFG Alliance, did begin exploring the possibility of making EVs on its redundant Adelaide site.

So far the plans have come to naught but a GFG spokesperson welcomed the ALP announcement this week.

“We continue to investigate not only the viability of the Australian electric vehicle market but also the potential to reinvigorate Australian car manufacturing,” the spokesperson says.

“We have received tremendous interest in our vision to bring Australian-made electric vehicles to the market and potential government support could make a real difference to our vision becoming reality.”

Emission omissions

However, the Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries believes “all low-emission vehicles coming into the Australian market will be sourced from international facilities”, and even EV advocates among long-time industry observers are sceptical about any prospect for bringing car manufacturing back.

Auto specialist Craig Milne of the Australian Productivity Council says you would need to persuade a multinational not only that it would be profitable to build here, but also that it could make more money here than in its factories elsewhere.

KPMG automotive expert Steve Bragg is blunt: “If you’re talking an everyday, mass-produced Toyota or something like that, then I think those days are over.”

But he does believe Australia could turn its hand to bespoke specialised vehicles — limited-run performance cars or trucks — and at least one Victorian operation is already proving him right.

Victorian start-up SEA Electric has found a niche converting commercial vehicles to electric power and has already expanded overseas to meet demand.

Chief executive Tony Fairweather says the challenges here — getting finance, high labour costs — are formidable but the rapid adoption of EVs overseas has opened a small window of opportunity for previous suppliers to Holden, Ford and Toyota.

“There are a large number of component suppliers who could easily transition to EV component supply,” he says.

“Motors, telemetry, software — the things we’re good at in Australia — we should be focusing on getting those industries up to scratch for export markets.”

Parts truth

So the EVs arriving on ships could have some Australian content, at least, and purely in terms of variety over the next few years the big brand names are racing to bring out as many as they can.

By some estimates, the industry as a whole will invest $US300 billion ($422bn) in the EV project and from just a handful of models in showrooms, there will be more than 70 to chose from by 2022.

Most of the activity can be traced back to the Dieselgate scandal of 2015, when Volkswagen was caught fiddling the emissions from its cars in the US, and the mood of regulators and buyers alike turned against internal combustion, particularly diesel.

Since then Volkswagen has striven to become a leader in EVs and its first cars, due next year, will herald an avalanche of models from across a brand stable that includes Skoda and Audi. Later this year, Mercedes will debut its first battery SUV, called EQC, joining the Tesla Model X and just released Hyundai Kona in supplying EVs to the most popular vehicle category. The dearth of choice, which many believe has held back EV demand, will soon be much less of a problem.

But to meet Labor’s expectations that half of all new vehicles should be electric by 2030, demand in Australia will have to take off. Last year we bought just 1352 EVs, a total that includes both pure battery-powered cars and plug-in hybrids, which combine an electric motor with a conventional engine and can travel short distances using lithium ion alone.

Plug-in hybrids are widely viewed as a bridging technologythat familiarises buyers with the different experience of EV driving and overcomes the issue of range anxiety — the fear of being stranded far from a recharging station with an empty battery.

Infrastructure is a chicken-and-egg problem for the EV proponents, because the lack of recharging stations discourages buyers, but a paucity of buyers means there’s little incentive to roll out stations.

However, another Australian EV success story is Queensland-based company Tritium, which builds some of the fastest and most sophisticated rechargers available.

It is suppling the Ionity network being rolled out in Europe and also Chargefox, which aims to have a string of 22 stations linking Adelaide to Brisbane by the end of the year.

Tritium co-founder Paul Sernia says we buy cars for the freedom they bring and without a refuelling network, the EV vision falls apart.

“We’ve seen overseas that without the charging infrastructure you struggle to support the electric vehicles on the road,” Sernia says.

“It should be coming before or at the same time as electric vehicles.”

Incentives needed

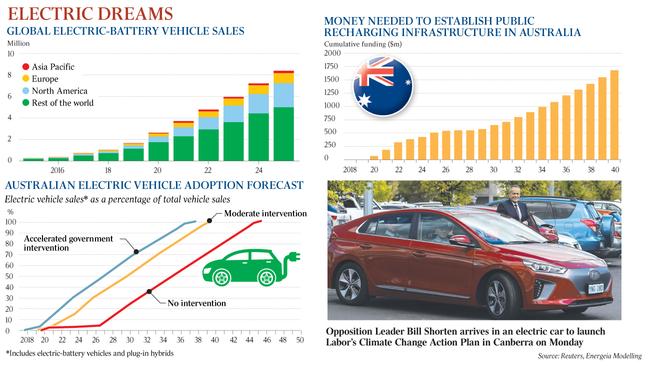

In its latest findings, EV research specialist Energeia says moderate incentives for EV take-up would fulfil the ALP’s vision but the charging network would need to expand exponentially.

With hundreds of thousands of EVs on the roads, Australia would need a network of about 8000 rechargers at a cost of about $700 million by 2030, while a further two million households would have installed domestic wall boxes to plug in overnight.

On the same assumptions, the network just gets bigger from there. Australia would need to spend $1.7bn by 2040 to install 28,000 public chargers.

How much of that money comes from government and how much from the private sector is an open question, but that’s just the tip of the spending iceberg.

The Energeia projections, in line with Labor thinking, suggest “moderate” incentives would be required, including policy support, changes to the luxury car and fringe benefits tax, standards for vehicle emissions plus preferential parking and use of transit lanes.

KPMG’s Steve Bragg says regulation and subsidies drive buying decisions “and most people would choose not to pollute”.

But if we did hit the ALP target, it would propel us to the front of the pack.

“We would go from lagging the rest of the world to leading them.”

The European Commission, for example, expects 15-30 per cent of new sales to be EVs by the end of next decade.

Many observers are more cautious than Energeia, with transport consultant Abmarc predicting Australian new car sales will be 28 per cent battery-powered by 2038, with nine out of 10 vehicles on the road still relying to some extent on internal combustion.

Abmarc’s Sarah Roberts says achieving the 50 per cent goal would take “very significant incentives from this very low starting point”.

A key factor here is the high cost of batteries, and while that has already fallen significantly, most hopes rest on game-changing switch to solid-state lithium ion systems by 2025.

Some EV newbies, such as the British appliance company Dyson, are relying on the technology from the outset.

Price parity arrives

But Roberts says the real challenge will be building mass-market EVs that are competitive.

“We have close to price parity now in the luxury segment — you can buy a conventional Range Rover or an electrified Range Rover for a very similar price,” she says.

“But where they’re really going to struggle is in the small car segments — under-$25,000 vehicles.

“At the low end of the market it will be really challenging for the manufacturers to make a battery EV with an acceptable range for the same price point.”

The luxury sector accounts for just one in 10 cars sold in Australia, with almost half — 46 per cent — of buyers last year paying $30,000 or less.

The most affordable EV on sale now is the Hyundai Ioniq, which starts at $45,000 before on-road costs. Its new Kona electric SUV starts at $60,000 when most buyers in that segment spend $50,000 or less.

Another EV advocate is Adam Hammond of sustainable finance company Bluetech, but he says persuading private buyers to go for battery cars is approaching the problem from the wrong direction.

“The low-hanging fruit in EVs is in the commercial space. For privately owned EVs, it’s going to take a lot of money.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout