Australia is not the first nation to argue over its national day

The French Revolution was a messy and extraordinarily bloody affair – but there are very few calls for Bastille Day to be cancelled.

That some national days have become an integral part of their country’s cultural landscape is beyond question. The French Revolution was a messy and extraordinarily bloody affair but there are very few calls for Bastille Day to be cancelled.

Independence Day

Even in the US, where the nation’s history has been transformed into a battleground, the 4th of July, Independence Day, retains its iconic status as a reaffirmation of the national project.

To say that is not to ignore the tensions and complexities associated with national days. Because they are just one day in the year, they impinge less on everyday life than other symbols of nationality, such as the national currency or the often ubiquitous national flag.

But equally, as the one day that centres squarely on the nation, and that is almost everywhere a holiday (which gives the day additional saliency), they inevitably focus attention on the celebration’s broader meaning.

It is consequently unsurprising that even the selection of a national day has, in some countries, proven extraordinarily difficult.

Germany’s Unity Day

Germany is an extreme case in point. During the German Empire (that is, from 1871 to 1918) the official holiday, Sedan Day (Sedantag), celebrated Prussia’s decisive victory over France at the battle of Sedan in September 1870 – a victory that opened the road to German unification. But that was hardly politically viable after Germany lost World War I, opening a long period in which the official holiday, May 1, was less a celebration of the nation than of labour.

The situation became even more confused in 1945 when the holidays that had been introduced by the Nazis were abolished. However, the massive revolt that began in East Germany on June 17, 1953, only to be crushed by Russian tanks, was clearly worth commemorating, with the result that the government of the Federal Republic declared June 17 the “Day of German Unity”.

But the achievement of German unity in 1990 made that holiday somewhat redundant – and November 9, 1989, the day the Berlin Wall came down, seemed to offer an entirely appropriate alternative, all the more so as it was Germany’s equivalent to the storming of the Bastille.

It didn’t take long, however, for Germany’s history to quash that option. It was on November 9, 1938, that Nazi storm troopers started the systematic destruction and looting of synagogues and Jewish businesses that came to be known as the Kristallnacht. To make things worse, in 1939 the Nazis, exemplifying their habitual perversity, had declared November 9 the official day of commemoration for the “fallen heroes” of National Socialism.

All that plainly ruled out November 9 as a celebration of the newly unified Federal Republic.

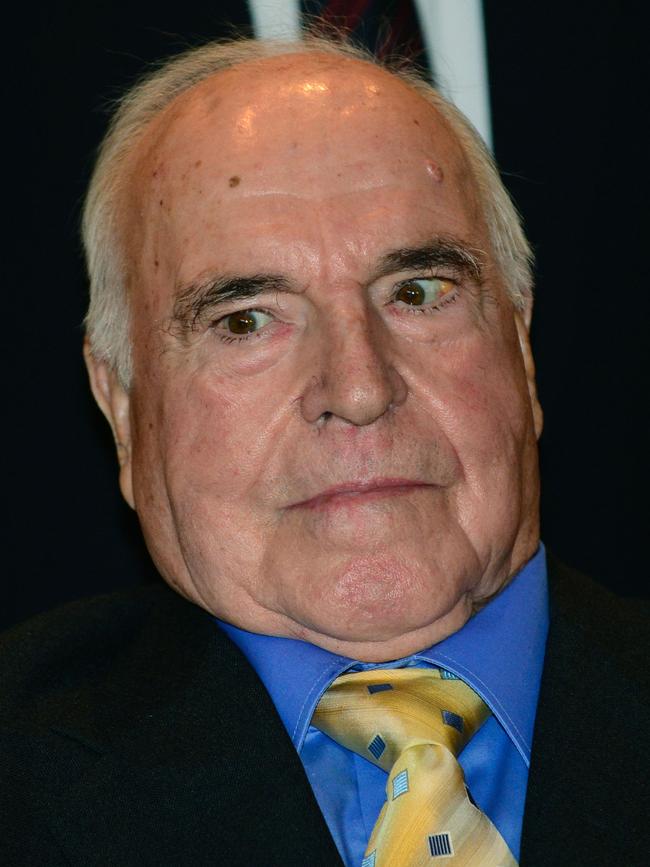

However, finding a day that did not have appalling connotations, yet resonated in the country’s historical consciousness, proved a remarkably fraught task. Chancellor Helmut Kohl therefore decided, with little public debate and even less discussion in parliament, that October 3 – the day chosen by the caretaker government that ran East Germany from the end of 1989 to October 1990 as the earliest possible date for unification – would be the newly reunited country’s national day.

That hasn’t ended the controversy, as polls show very few Germans understand or appreciate the day’s significance. But the celebration may not be entirely ill-conceived. After all, it was on that day that the German Democratic Republic, whose history was one of relentless persecution, officially ceased to exist, with the extension to the GDR’s former territories of the Federal Republic’s 1949 constitution. In that sense, it marked the triumph of the constitution’s vision: a vision of a Germany based on liberal values, respectful of human dignity, anchored in the best, not the worst, of the country’s tradition.

In 1958, the German Constitutional Court declared, in its so-called Luth decision, that the “objective principles” embodied in the constitution’s enumeration of “Basic Rights” permeated and delineated the Federal Republic’s entire legal order.

And shortly after that, Dolf Sternberger, an eminent German philosopher and political scientist, introduced the concept of “constitutional patriotism”: the notion that the uppermost form of loyalty, for post-war Germans and post-war Germany, was not to the soil or to any concept of the race – as had been the case under Nazism – but to the liberties, rights and obligations that are at the heart of the constitution.

A genuine inheritance of the German Enlightenment, those liberties, rights and obligations deserved not merely respect but the reverence Sternberger saw as one of the enduring strengths of Americans’ attitude to their constitution. There would be, for sure, sharply differing views as to those principles’ implications; nor would they ever be completely realised in the face of life’s uncertainties and humanity’s imperfections.

But the greater the citizens’ love of the laws and common liberties, Sternberger argued, the greater the assurance that the country that had inflicted such horrendous harm on the world, and suffered so much itself, would build a “home for freedom”. It was, in short, not a question of erasing the past but of celebrating an aspiration that could unite all Germans for a better future.

Bastille Day

Much the same, it could be said, marks the tumultuous history of Bastille Day. While its status is now unquestioned, that was certainly not true in the revolution’s immediate aftermath. With the holiday being abolished by Napoleon, any attempt to celebrate July 14 was treated as treasonous under the Bourbon regime that returned to power in 1815.

Tentative moves in the direction of marking July 14 were made in the wake of the 1830 revolution that led to the founding of a constitutional monarchy. But the memories of 1789 remained too divisive for those steps to come to fruition.

“The crimes of the revolution”, argued the holiday’s parliamentary opponents, had begun on July 14, 1789, and it was then that “the disastrous principle of disorder” had “invaded” French history; to officially sanction a “revolt against the constitution and the laws” would endorse anarchy and sanctify mayhem. And far from ending then, the polemics continued for decades, reaching new peaks of passionate intensity after the fall of Napoleon III in 1871.

Using the liberties that came with that regime’s end, Leon Gambetta, a radical republican, organised festive banquets, framed by tricolour flags and fanned by revolutionary songs, on July 14, 1872.

Declaring “The fourteenth of July was the Revolution that emancipated everyone”, Gambetta invoked the “tears of joys that had been shed wherever there were magnanimous souls when it was learned that the Bastille, this fortress of tyranny, this dark symbol of oppression, had been destroyed”. No greater day could be found, he concluded, for celebrating France’s commitment to the “eternal spirit of liberty”.

The counterblast from the conservative press was prompt and scathing. The victors of the Bastille, “of whom Gambetta speaks with admiration”, were, the leading royalist paper said, “a group of murderers” whose misdeeds it vividly illustrated with gory images of decapitations.

But as balls commemorating July 14 spread throughout France, the momentum was very much in Gambetta’s direction.

In 1879, when Jules Grevy beat the monarchist Marshal MacMahon to become the first republican president of the Third Republic, Gambetta’s proposal finally triumphed, with the National Assembly passing legislation that made Bastille Day a holiday on June 8, 1880.

Bastille Day nonetheless remained bitterly contentious until 1945. Only after the fall of Vichy and the liberation of France from the Nazi yoke did the day begin to gain a more consensual significance. It was not a matter of glorifying the revolution, much less the Terror it had unleashed; it wasn’t even a celebration of the storming of the Bastille, a poorly judged affair that cost more innocent lives than it freed.

Rather, for all the revolution’s blood-soaked faults, July 14 defined a set of common values – “liberty, equality and fraternity” – that are the finest aspect of its legacy. Insurrection, Voltaire had said, is the only invention of the French, and Thomas Carlyle described the ability to bicker and disagree as “the talent that distinguishes the French People from all Peoples, ancient and modern”.

But the depths of those divisions, it was increasingly recognised, made it even more important to remember what all French men and women could hope for: a country in which the ideals of 1789 came closer to being a reality.

It would be nice to think we have it in us to learn from those experiences. Historical events need to be faced, not defaced. We can celebrate foundational events such as Australia Day without reducing them to a Manichean choice between good and evil, sin and virtue: as John Stuart Mill aptly put it, “Ages are no more infallible than individuals”, our own included. Rather, the point is that foundational events are foundational: they set a beginning whose course always remains to be shaped. And by maturely commemorating those events we can find, as others have, the enduring values to steer us along that course and make our common future one all Australians consider well worth having.

When the French revolutionaries specified in the constitution of 1791 that a day of national celebration was to be held each year to “preserve the memory of the French Revolution”, they began a trend that could rightly be viewed as one of France’s most successful exports. Today, a mere handful of the world’s 200 or so countries lack a national day – and even those that do typically have a regional holiday, such as England’s St George’s Day, in its place.