Australia is not racist, but the voice could make it so

Subsidise grievance and you’ll get more grievance; that’s identity politics. A Yes victory would be a tragedy, and threaten much of the astonishing success of modern Australia.

However, if the referendum to install a voice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to parliament and the executive is successful, our politics and society will become increasingly racialised, with greater racial polarisation and hostility.

The voice would inject race into the Constitution in a way that it’s not there now, with likely awful results. It will imprison Aboriginal Australians in a stereotyped racial identity and, for the first time since 1967, formally enshrine the division of Australian citizens into unequal races. This would be a tragedy of epic proportion, and threaten much of the astonishing success of modern Australia.

The idea Australia is especially racist is absurd. Racism exists in parts of our society, there are some racist people around, and even people not fundamentally racist will occasionally act or speak in racist ways. But it’s less than anywhere else. If you inject race into the heart of the Constitution, and into every political debate in the future, you guarantee radically increased racial conflict. The voice would distort the Constitution which, for all its sins, is perhaps the best in the world. It’s not perfect, far from it. But as Winston Churchill remarked of democracy, it’s “the worst possible system, except for all the others”.

How can we establish that Australia is less racist than most? We must rely on evidence rather than our sense of things, but our sense of things counts. The evidence? When the British set up a settlement in Sydney in 1788, racial assumptions were ubiquitous in virtually all human societies. When our Constitution was adopted in 1901, race was still a central concept, though under the influence of Christian and Jewish universalism its salience was declining.

One of Australia’s first laws was the White Australia policy. That’s racist policy by today’s standards, but it’s meaningless to mis-apply today’s context to events more than 120 years ago.

In 1966, Liberal prime minister Harold Holt moved to end the White Australia policy. Since the 1970s Australia has had racially non-discriminatory immigration policy. Except for a preference for New Zealanders, which isn’t racial but based on historic ties, our policy is the world’s most racially neutral.

Even in White Australia days there was substantial non-white immigration. In Sydney as a kid in the early ’60s I had classmates from Singapore and New Guinea. With a population now of 27 million, Australia has a third of its people born overseas and about half have at least one parent born overseas. This is a higher proportion of immigrants than almost any other nation. There are nearly 1.5 million ethnic Chinese Australians. A million Australians have an Indian or other South Asian background. We have countless other ethnic backgrounds.

On marriage it’s impossible to get precise statistics, partly because people don’t marry a race, they marry an individual, and generally don’t conceive of their marriage in racial terms, but Australian racial inter-marriage rates are very high.

There’s hardly another country with a record of consciously moving so comprehensively from near homogeneity to pervasive racial diversity. And it has been done with virtually no trouble.

In Australia, racial discrimination is illegal. More than 55 per cent of the Australian landmass has been given to native title. A Productivity Commission report in 2017 found we spent more than $33bn a year on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Most of that was regular money on services such as hospitals, schools and so on, but it included $6bn on specific programs for Indigenous Australians. Per capita spending on Indigenous Australians was about double the national average, mainly because it’s expensive to deliver services to remote and provincial areas. Many Indigenous people experience disadvantage, so need services such as hospitals more often. Spending today must be $40bn.

Since World War II, hundreds of thousands of refugees have settled here. In an almost unique historical episode, many Italians who were prisoners of war in Australia during World War II came back later as migrants, married and raised wonderful families. People from around the world yearn to live in Australia because of its abundant opportunities, its reliable and colourblind rule of law, its social, political and constitutional stability, and its ready acceptance of diverse races and religions.

There’s a lot to like in that big picture. No doubt much could be done better. But it’s ridiculous to characterise that society as a swamp of racism.

What about our sense of things? Let me offer a personal note. My wife of more than three decades comes from Malaysia and is of Indian, Punjabi, background. So are our three sons, of whom I am insanely proud. For all of their childhoods, we lived in inner-western Sydney. We were constituents of Linda Burney’s when she was a member of the NSW parliament. I would have been intensely hostile to any discrimination directed against my family. But it was never there. The boys didn’t grow up amid a swamp of racism because there isn’t a swamp of racism.

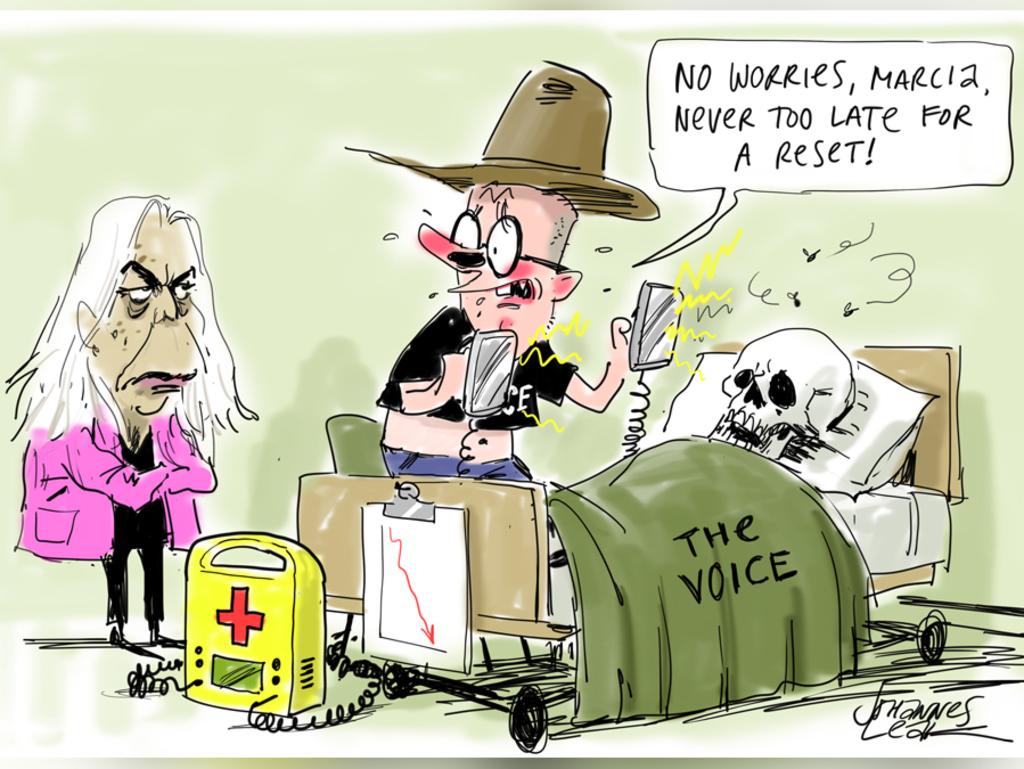

The debate around Anthony Albanese’s referendum has been shockingly divisive. Some folks on both sides have said hateful and offensive things. The misery of the debate is an excellent forecast of what the tone of debate will be if the voice is established in the Constitution.

If you place race at the centre of institutional and constitutional life, race will assume much greater salience in politics and society. If you subsidise grievance, you’ll get a lot more grievance. That’s the crazy spiral of identity politics.

While some on both sides have engaged in excess, the Yes campaign has been structurally offensive because at no point does it accept any arguments for the No case as legitimate. It’s not necessary to agree with your opponents’ arguments but you can surely acknowledge that some are legitimate. Burney herself labelled the case that the voice contradicts the democratic principle of equal citizenship an example of Donald Trump-style, dangerous dishonesty. Yet the voice plainly does exactly that. Some of the most sensible people make that argument.

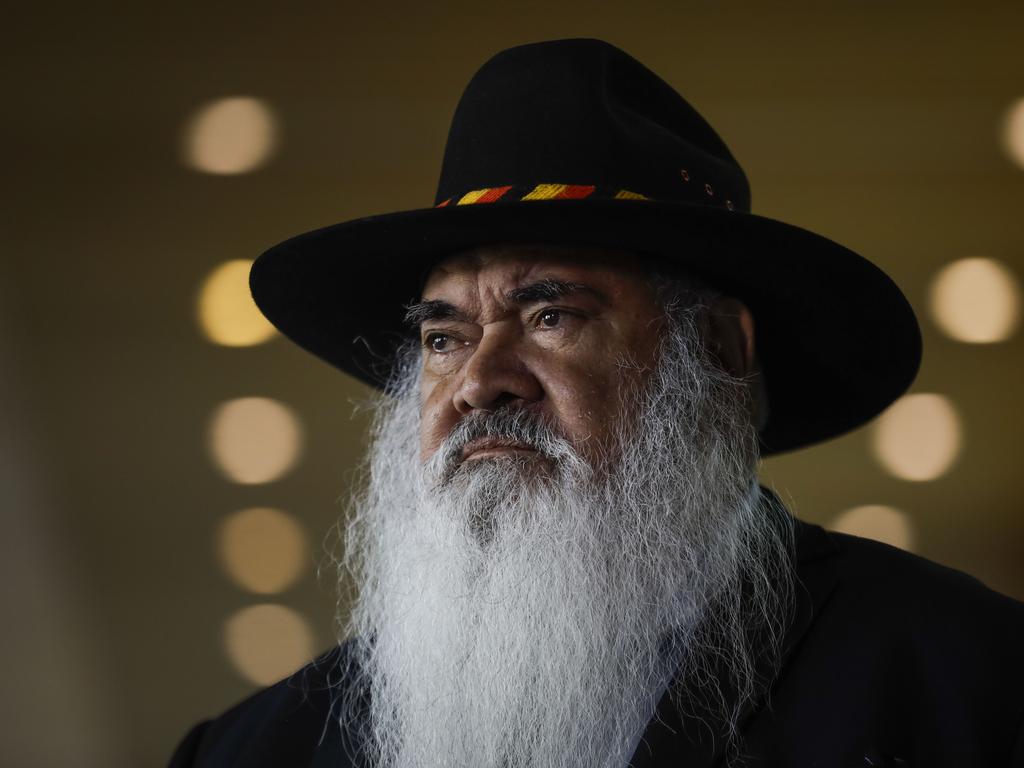

Again, Langton is representative of the Yes case when she declares: “Every time the No case raises one of their arguments, if you start pulling it apart you get down to base racism – I’m sorry to say it but that’s where it lands – or just sheer stupidity.” She has also said of Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Bess Price that they “have become the useful coloured help in rescuing the racist image of these conservative outfits” (such as the Centre for Independent Studies). Noel Pearson famously declared that if the No case went low, the Yes case would go high, that where the No case expressed hatred, the Yes case would respond with love. Yet he also said of Price and Warren Mundine that they were black fellas manipulated by whites “to punch down on other black fellas”.

Anyone else would be drummed out of public life for speaking like Langton and Pearson. And remember, the Yes case is on its best behaviour, trying to win a referendum.

One reason millions of Australians will vote No is that they are instinctively, sensibly, very cautious about changing their Constitution. Despite all the ferocious debate there has been little proper discussion of the Constitution.

Peter Dutton’s worst mistake was to promise a second referendum to achieve constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians. In today’s context, that’s crazy. It provides the only argument for voting Yes. If you do, you’ll only have to vote once.

In truth, there’s no danger of Dutton, if he ever becomes prime minister, following through with a referendum. Such a proposal when put by John Howard with the republic referendum in 1999 was defeated even more heavily than the republic. Dutton would not get unanimity in his party or Coalition. The Aboriginal activist class is dead against it. It’s unlikely Labor would hand Dutton a victory by furnishing bipartisan support. And there’s no guarantee it would pass if put to referendum. So really it just furthers the tradition of happy silly fantasy talk about the Constitution, which has got us into the mess we’re now in, and of which the Liberals are as guilty as Labor.

It also betrays a failure by Dutton to grasp fully the nature and genius of the Constitution. In 2018 the parliamentary joint committee on constitutional recognition of Indigenous people produced a vague and woolly report. Amanda Stoker, then a Liberal senator, went along with the recommendation of a co-design process, but in remarks of great importance essentially rejected constitutional change. The Liberal Party, with its relentless will to self-harm, denied Stoker a winnable place on the Senate ticket for the last election. Her remarks on the report are some of the most important, insightful and honest, before Price coming to Canberra, heard on the Constitution.

Stoker said: “Those who expect constitutional recognition to be a panacea for this diverse bag of practical problems are bound for disappointment … No one considered in their submission: what is the purpose of our Constitution?… If the purpose of our Constitution is to mechanically allocate the powers and functions of a federal government – and that is its purpose – then all bar one of the proposals for amendment is misconceived … the Constitution is not an emotional document; indeed to insert emotion in a document with a legal purpose and operation invites judicial activism … It would be a mistake, in my view, to entrench any form of identity politics into our Constitution … the Constitution is a legal and mechanical, rather than a poetic or cultural, document … (There is) good reason to maintain a narrow and legal purpose for our Constitution, and avoid adapting it to symbolic, emotional or cultural purposes.”

Some constitutions set out the existential or moral purpose of their nation, often in soaring prose. Splendidly democratic constitutions can be found in the old communist dictatorships. In a real democracy, where a Constitution uses grand language, this generally results in power for the highest court. If your constitution guarantees justice, liberty, human fulfilment, politics moves into the courtroom as judges determine what all these words mean. That’s intensely undemocratic. Some countries – like Britain, New Zealand and Israel – avoid this problem by not having a written constitution. That can lead to worse problems.

Australia’s Constitution is a work of genius. You can’t altogether stop judges from interfering in politics, but our Constitution is so tightly, technically, dryly written, it limits that a good deal. It’s a mechanical document – how many senators, when to have elections, the role of the courts, and so on. Marvellously, it doesn’t distinguish one Australian from another on grounds of race. It did before 1967, it doesn’t now.

Australians are defamed for being cautious about constitutional change. In fact, they show a rock-solid common sense, understanding that the predictable, unpoetic, mechanical, well-understood document they have is much better than anything that might replace it.

In 1977, three referendum questions passed. Each represented a small, specific change, received bipartisan support and fixed a specific problem. For example, one made it mandatory that when a senator resigns or dies mid-term, they must be replaced by a person of the same political party.

The 1967 Aboriginal referendum is spectacularly misrepresented. It asked for approval for “An Act to alter the Constitution so as to omit certain words relating to the People of the Aboriginal Race in any State and so that Aboriginals are to be counted in reckoning the population”. Previously the Constitution had guaranteed states controlled Aboriginal affairs. The Constitution said the federal government could make laws regarding any race except Aboriginal people. The provision not to include Aboriginal Australians in the population figure, though they were always counted in compiling the census, arose out of disputes between states about who got what money, and also how many seats in parliament each state got.

This referendum won more than 90 per cent of the vote. It had the effect of removing the only two references to Aboriginal Australians from the Constitution.

It’s worth going back to the history books or archives to look at the campaign material for the Yes case in 1967. Although the actual changes were modest, the campaign was all about giving Aboriginal Australians absolute equality, making sure they suffered no official discrimination, giving them exactly the same civic status as everyone else. A popular campaign song said: “Give them rights and freedoms just like you and me”.

But we’re frequently told the Constitution today contains provisions that apply only to Aboriginal people. That’s not true. There are two sections that refer to race and neither refers explicitly to Aboriginal Australians. Section 25 prevents a state gaining seats in parliament on the basis of people they’ve disqualified from voting by reason of race. It’s illegal now to discriminate on grounds of race in Australia. This is a complete dead letter and should be deleted, except no one could be bothered because it has no effect.

Section 51 (xxvi) gives the commonwealth the power to make laws concerning the people of any race. So, theoretically, all Australians are covered by that clause.

What about land rights? The Mabo case did not require the race power. Rather, it was a common law decision that where a community had continuously possessed land, and maintained an association with that land, this form of title, which preceded British settlement in 1788, would be recognised in Australian law.

Very few laws have ever been passed under the race power. The only laws that conceivably require it are native title and protecting Aboriginal cultural heritage. You could easily frame cultural heritage laws in a non-racial way. If you must reform the Constitution, it would be better for lawyers to work out narrow, non-racial ways the commonwealth could protect native title without the race power. Stoker, among others, thinks this could easily be done.

But Australians are practical and empirical in approaching the Constitution. They won’t change unless they see a benefit to change. Nothing in the Constitution prevents Australia doing anything with, for or by Indigenous Australians. There’s no practical benefit in creating another voice. Bad policy comes not from the lack of a voice – there are countless Indigenous consultative mechanisms – but from listening to bad advice from the wrong voices. The Northern Territory government, in its disastrous, later reversed, decision to end grog bans, listened to Aboriginal voices that wanted the bans ended. The women who wanted not to be bashed, or see children abused, by alcohol-affected men, were the voices that should have been listened to.

The Constitution contains a race power and it would be better if race had no role in the Constitution. That’s why, pace Dutton, it’s probably a bad idea to pursue recognition via constitutional means.

In 1967 the government simultaneously put another referendum question, to cut the nexus between the number of senators and the number of House of Representative seats. It had bipartisan support. The government thought the goodwill from the Aboriginal referendum would help it pass. Only six senators opposed it yet it failed dismally, barely scraping 40 per cent of the vote.

Where does all this leave Aboriginal disadvantage and the gap in life expectancy and the rest?

Price is right that most Aboriginal Australians are not disadvantaged. The further away they live from capital cities the more disadvantaged they are. Twenty or 30 per cent of Aboriginal Australians are disadvantaged.

Price has the most constructive suggestion – a full forensic audit of how all the money notionally spent delivering services to disadvantaged Aboriginal people is actually spent.

The voice, like previous big picture Aboriginal consultative bodies, and as its advocates have previously said, would quickly get involved in pressing for a treaty, pushing divided sovereignty, supporting effective separatism, campaigning for vast new expenditure, and endless denigration of almost all Australian history.

It’s a certain recipe for racial conflict and offers almost no prospect of betterment for Aboriginal lives.

As Price observes, most Australians are filled with goodwill, indeed with love, for their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fellow Australians. But Price and Mundine are surely right that advancement for Indigenous Australians won’t come through constitutional change. Concentrating on the Constitution is at best a distraction. At worst, it’s very bad indeed.

Australians live in a swamp of racism, according to voice co-designer Marcia Langton. Langton is wrong. On any objective measure, Australia is one of the world’s most racially inclusive, least racist, societies.