And yet the latest opinion polls indicate that most voters do not wish to alter the date of Australia Day. A mere one third of voters wish to call it “Invasion Day”. Indeed, most people value the day and silently shun the Melbourne vandals who, this week, cut off the ankles from the statue of Captain Cook. These wreckers maybe are products of an education profession which, more than ever before, is inclined to denigrate its own nation.

Is our history a standing disgrace? The more indignant critics of Australia Day say that it glorifies what was really a prolonged catastrophe. It is true that for decades the Indigenous people mostly died from diseases to which they had no immunity. It is true that in frontier conflicts they were killed in large numbers, more dying after 1860 than before. Some of the killings were notably brutal.

The whole truth, however, can be elusive. We are easily mistaken, each one of us.

We still hear the allegation that the Indigenous were not deemed worthy of being counted until 1967, or if they were counted they were classified under the fauna and flora laws. This is a deliberate slur against the Australian people and yet it circulates freely in Aboriginal and sporting circles.

It is regrettable that many Aboriginal Australians were long deprived of voting rights, but this is only a fraction of the total truth. Most Aboriginal men in Victoria, NSW and much of South Australia had an early right to vote – if they so desired. They could exercise the right as early as 1860, a year when huge numbers of British and European men did not yet have a vote. Incidentally, an Aboriginal man, a well-off master builder by trade, sat in parliament in Sydney as early as 1889 – some eight decades before the first Aboriginal person sat in federal parliament. He was entitled to feel proud, for he had convict as well as Aboriginal ancestry.

In Adelaide at the 1896 election, many Aboriginal women were seen to be voting at a time when – according to my reckoning – white women in the 10 major cities of the Western world had no vote. In wartime, few full-blood Indigenous people fought for Australia, but in World War II the Torres Strait Islanders on Thursday Island – according to one distinguished war historian – provided more servicemen, in proportion to population, than any other town in the nation.

It was a common lament of Indigenous people that they were totally dispossessed by the “invaders”, but this has been more than remedied. They now own a very high percentage of the nation’s lands, indeed more than is owned by the Maori in New Zealand.

Aboriginal Australians, few in number, control at least 55 per cent of Australian soil. It is the wish of Anthony Albanese that by the year 2030 they should own or control 70 per cent. And yet the present system of land rights seems to show serious flaws. Alas, the Indigenous people living on these collectively owned lands do not have a right prized by most other Australians – the right to own their own house. Do they even gain a fair share of the income generated by these lands? We do not know.

The latest census reveals that a surprisingly large group of large-town and city Aboriginal families are prospering. To their credit, they are, for example, buying their own home, they have two cars in each household, and their children are staying on at school or gaining tertiary certificates or degrees.

Good news does not always reach the television news. These prospering Aboriginal families probably outnumber their kinsfolk who live in the small and remote bush towns, have no or only intermittent jobs, and rely on very heavy welfare subsidies.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart, though successful in uniting Indigenous peoples, should be re-examined. The key document in the voice referendum held last year, it insisted in poetic language that all Indigenous peoples were bonded spiritually to the specific homeland where they were born. Their souls or spirits “must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors”.

A shock to these affirmations of spirituality was delivered by the census held nationwide in 2021. It revealed that the Uluru Statement was preaching a myth. In fact, most Aboriginal Australians today are not worshippers of an Indigenous religion. In the Northern Territory, still viewed as a stronghold of the ancestral religion, 94,000 of its Indigenous peoples are Christian but only 3400 worship an Aboriginal religion. Across the nation as a whole, fewer than 2 per cent of the Indigenous people declare that they worship an “Australian Aboriginal traditional religion”.

Actually, they are more Christian than the mainstream Australians who live in the capital cities.

Most of these Aboriginal Christians probably would not conceive of themselves as primarily victims of the so-called Invasion Day. After all, it was this so-called invasion which, year after year, spread the very religion they worship. Indeed, the Torres Strait Islanders were so grateful for the arrival of the London Missionary Society in 1871 that they still designate it not as Invasion Day but the Coming of the Light.

Australia Day should commemorate not only the significant landing in 1788 at Sydney Harbour, as seen by both sides, but also themes in Aboriginal history. One vital insight came from the geologist Jim Bowler who, half a century ago while on several journeys, discovered the revealing remains of an Aboriginal woman and man at Lake Mungo in NSW.

With the aid of radiocarbon dating, his discoveries proved beyond doubt that the Aboriginal peoples explored and ingeniously utilised this continent long before other human beings even reached North and South America. Now living quietly in his homeland, South Gippsland, Bowler is rightly honoured for his contribution to world history.

Why is January 26 often denounced as the start of a shameful invasion? Governor Arthur Phillip never saw himself as ready to invade Australia. He was not even certain that Sydney would succeed as a settlement: it did not grow enough to feed itself. At first he did not want his marines and convicts to occupy land more than a day’s walk from Sydney Harbour. His instructions from London, which he tried to honour, were to live in peace. How can he be called the blameworthy head of an invasion?

When, three weeks after reaching Sydney, Phillip set up a another British settlement he did not choose fertile Aboriginal land nearby. Instead, he shipped an expedition of 23 men to a remote and uninhabited place unknown to Aboriginals. Out in the Pacific Ocean, far east of Brisbane, Norfolk Island is still the second-oldest British settlement in Australia. Its inhabitants certainly have no reason to talk of Invasion Day.

Many historians and Aboriginal activists will probably continue to deplore January 26. Annual ceremonies are already conducted to bring humiliation to Australia Day. Thus the next National Sorry Day is to be staged on Sunday, May 26.

Spurred by a determination to remember the so-called stolen generation, Sorry Day demands that the nation acknowledge “the wrongfulness of the past dispossession, oppression and degradation of the Aboriginal peoples”. It forgets that some form of oppression and degradation and dispossession – including wars with very high casualty rates – must have been familiar throughout the long and often-successful reign of Indigenous peoples.

Sorry Day posters are specially printed for schools. One poster for children enrolled in years three to six will give them information so that they can “defend the assertion that Australia was invaded”. Another poster provides an unfavourable perspective on Captain Cook’s landings in eastern Australia in 1770. In fact, Cook normally respected or even admired the Aboriginal people whom he saw or met: “In reality they are far more happier than we Europeans.”

In any case, today’s Aboriginal Australians have every right to argue that Cook did not discover Australia. Their own ancestors made the original discovery of global importance; and Cook, arriving eons later, actually rediscovered eastern Australia. He achieved something else; when he sailed away he had inspected and charted more stretches of Australia’s coastline than any single Aboriginal person could ever have visited.

At schools on Sorry Day this year, young children will be encouraged to hear a poem composed specifically “to promote thoughtful discussion”. It also, intentionally or not, invites them to dislike their country. Called I am Sorry, the poem’s first verse closes with a confession:

“For the failings of my ancestors, I feel compelled to say,

That I am sorry for all they did, and all they took away.”

In the school room, will small migrant children fresh from China or the Ukraine, or will Aboriginal children, have to recite the same confession?

A longer national event called NAIDOC usually enlivens a week mid-year. The Albanese government has just announced special grants to reward participants. This year’s slogan is Keep the Fire Burning! Blak, Loud and Proud. The word Blak is not a spelling error.

That week will honour “the enduring strength and vitality of First Nations” in the face of long “mistreatment”. It also offers an opportunity to “celebrate the oldest living culture in the world”. Unfortunately, that was the misleading slogan favoured by the Prime Minister during the voice referendum.

So far, evidence has not been amassed to prove that Indigenous Australians actually possess the world’s oldest living culture. It is worthwhile to search for the evidence but any search has to be worldwide and cover tens of thousands of years.

Likewise, the importance of Aboriginal Australians’ spiritual connection to the land is still over-emphasised by the law. In 2020, this attitude shone out in the court cases of Love and Thomas versus the Commonwealth of Australia. The men were born in Papua New Guinea and New Zealand, were not Australian citizens and, after being each convicted in Australia of a serious crime, were liable to be deported.

They appealed against deportation, especially pointing out that they were partly of Aboriginal descent. After the case reached the High Court, each of the seven justices wrote in fluent prose a different set of arguments The final judgment, a victory by four to three, enabled the convicted men to live permanently here.

Pivotal to the court’s thinking was the faith that a segment of one’s being – the part that was of Aboriginal descent – was so powerful and penetrating that a person thus endowed was superior to other Australians in certain rights. In the words of one judge, the “identity of Aboriginal people, whether citizens or non-citizens, is shaped by a fundamental spiritual and cultural sense of belonging to Australia”.

To observe the decline of the Aboriginal sentiment of spirituality is not to belittle its merit. For a long span of time it suffused the lives and deaths, and fears and longings, of these people. They believed that they were the reincarnation of their ancestors, those same ancestors who had created trees, rocks, hills, creeks and every other aspect of the existing landscape as well as the nightly stars in their millions.

The Aboriginal peoples’ immortal ancestors empowered or inspired them whenever they chanted for rain to fall, an ill woman to be healed, or their fellow tribesmen to make a surprise attack on enemies and kill them. One of the nation’s most scholarly books describes in detail this sacred world. Songs of Central Australia was written by TGH Strehlow after the childhood he spent with Aranda-speaking children and the years he spent travelling with camels in their homeland.

Is this a day to deride? No, it is a day for reflection. Australia has enjoyed far more successes than failures, though the failures are undeniable and numerous. Today, measured by several indicators of wellbeing and achievement, Australia stands near the top of the ladder of nations. It is one of the world’s oldest, continuous democracies. In a year of rich harvests it feeds – through its inventiveness in farming – perhaps 100 million people in other lands.

Its standard of living makes it a paradise for most of today’s immigrants – compared with the lands they left behind.

These are some of the powerful reasons why Australia Day is worth celebrating.

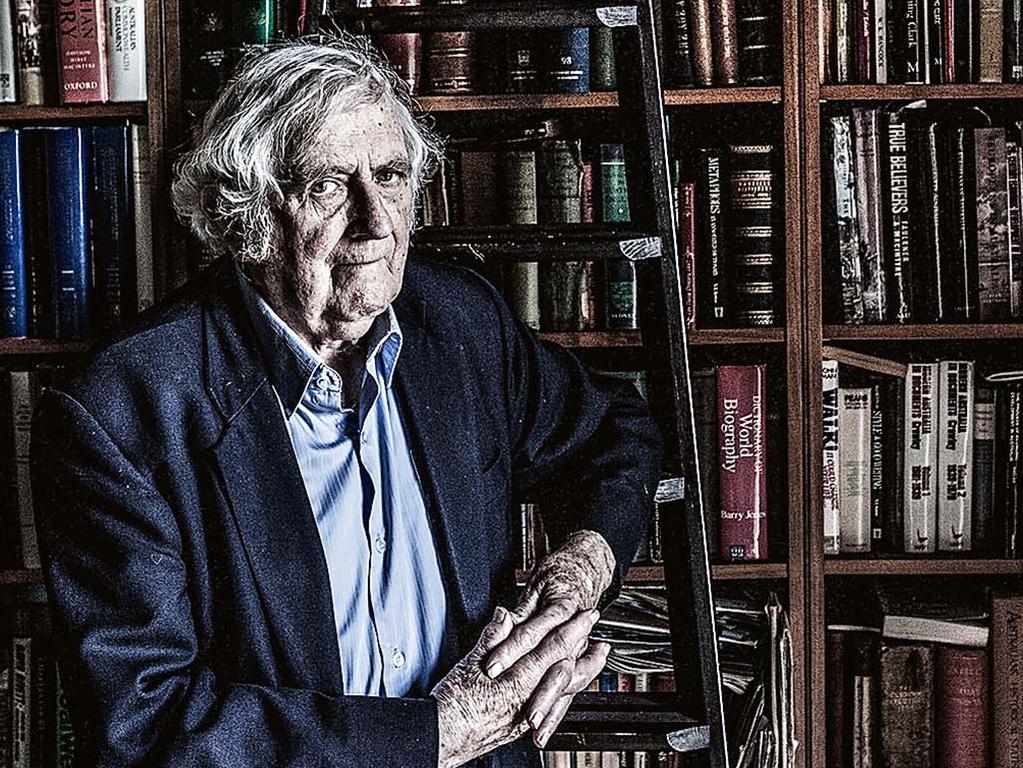

Geoffrey Blainey has written 40 books, mostly on Australian history.

When you read the daily news, you often gain the distinct impression that Australia Day is approaching extinction. Many critics say that its death should be hastened.